The Thinkhouse Review: COVID-19 and the ‘seamy underbelly’ of UK housing

A flurry of new reports sheds light on housing’s interaction with the economy. Martin Wheatley digs out the lessons in this month’s Thinkhouse Review of housing research

One thing COVID-19 doesn’t seem to have disrupted is the autumn harvest of housing research and policy reports that tends to emerge after the summer holidays, when authors hope the people whom they are trying to influence may be in a receptive frame of mind.

I have been lucky (or maybe unlucky) to have been assigned the review slot for the 24 reports published in September. They shed very interesting light on lots of topics about housing and its interaction with the economy and society: housing and health, development, homelessness, and the implications of the pandemic. Please do browse them on the Thinkhouse website. I only have space, unfortunately, to discuss the dominating issue of coronavirus, and a couple of reports on the seamy underbelly of UK housing.

One could sum up the common theme of the coronavirus reports as: “we didn’t mend the roof while the sun shone” – we didn’t address vulnerabilities in housing and other aspects of society that were well known and understood.

Starting with the direct health implications, The King’s Fund has produced a review for the Centre for Ageing Better about how sub-standard homes make the people who live in them more vulnerable to coronavirus and contribute to the increased non-coronavirus death and disease we have seen. Among the impacts considered in the report, the effects of cold and damp on respiratory health, of overcrowding on susceptibility to illness, of poorly maintained homes on the risk of accidents, and of homes without light or access to outdoor space on mental health were all known issues before the pandemic. We also knew that they aligned with factors including poverty and ethnicity, which so often lead to unequal outcomes, with even more tragic consequences for those affected by coronavirus. We can only hope that, having been brought into the limelight, there is now greater determination to fix existing homes and make sure new ones promote good health.

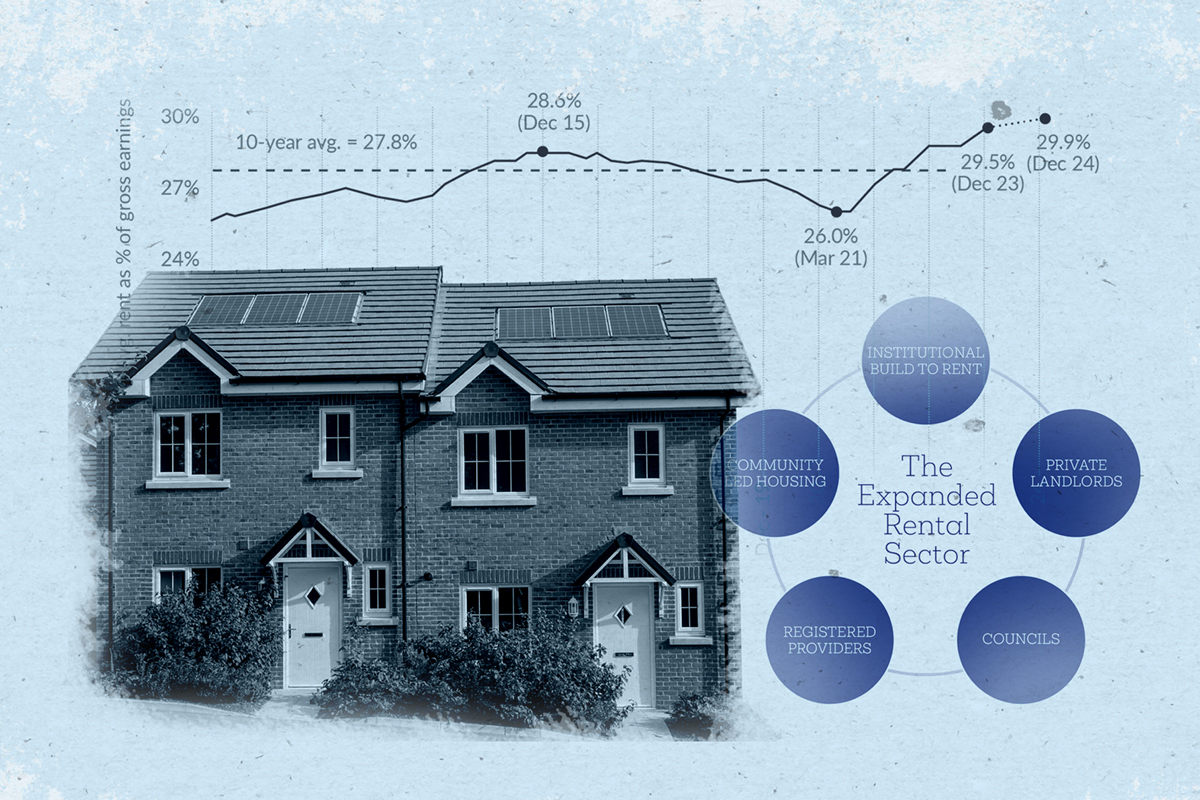

Other reports look at the indirect and long-lasting economic impacts of the pandemic on housing and labour markets. Shelter’s Renters at Risk characterises the crisis as three-fold: “A global pandemic… a resultant economic crisis… And these crises are taking place in the midst of a long-standing housing crisis.”

A society in which far too many lower-income households are financially stretched by the cost of renting in the private sector is going to face severe strains if there is an economic shock that further suppresses earnings and employment. We also know that homelessness and joblessness are linked, in both directions. The Centre for Homelessness Impact’s report shows how the aftermath of the pandemic is likely to increase the risks of worklessness leading to homelessness and to make it more challenging to get homeless people into employment.

The Affordable Housing Commission’s proposals for a National Housing Conversion Fund offer a good policy answer: public investment not just in new homes, but buying up existing, currently private rented homes. The Resolution Foundation’s report on the implications for owner-occupation is, to a degree, less pessimistic. It suggests that many owners have more financial resilience – although recent, younger buyers with high loan-to-value mortgages are more at risk.

Last but not least, a couple of sobering reports on under-researched aspects of the housing market shed light on why we need stronger standards and regulation to stop vulnerable people being ripped off and abused.

Colin Wiles has produced for the Intergenerational Foundation the first (so far as I know) serious analysis of ‘micro-homes’ – or, as the report title describes them, Rabbit Hutch Homes. His report offers a powerful challenge to neoliberal economists and breathless property journalists who have marketed homes with less floor space than a standard parking space as a “solution” to the housing crisis. As he points out, there is too little data about this rapidly expanding part of the housing sector. But the evidence he has pulled together indicates that such homes are, as he puts it, “a short-term solution that does nothing to tackle the underlying structural problems in the UK housing market”.

A partnership between housing justice charity Cambridge House and the University of York has taken on the difficult task of building evidence about the “shadow private rented sector”. Its report lays bare how “vulnerable tenants are targeted by criminal landlords and letting agents deliberately undertaking multiple breaches of tenancy and housing law in order to maximise their rental profit”. I defy anyone to stay calm reading its analysis of how an inadequate legal and regulatory framework, and under-resourcing and institutional indifference, enable this criminality to flourish.

Martin Wheatley is a board member at Greatwell Homes and an advisor and researcher on housing and government effectiveness

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters