You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

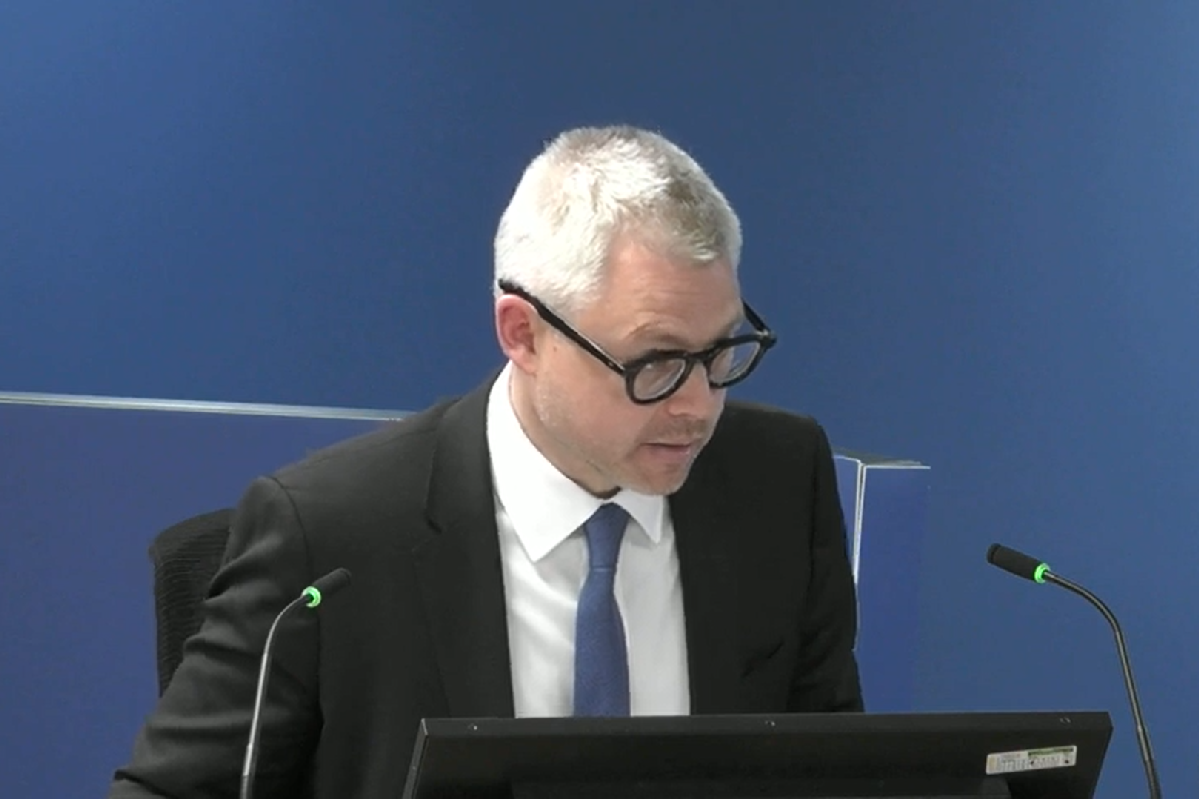

UK global ‘outlier’ on ‘stay put’ policy, expert tells Grenfell Inquiry

The UK is a global outlier when it comes to the ‘stay put’ policy, a fire safety expert has told the Grenfell Tower Inquiry.

Giving evidence to the inquiry this afternoon, Professor José Torero said there is no reason why a stay put policy is “beneficial or necessary” and that the UK is “is truly an outlier” in not providing a Plan B should it prove untenable.

Last week he presented a report to the inquiry which concluded it was “essential” that the stay put policy for high-rise buildings is “abandoned” because the risk of fires spreading externally cannot be properly assessed under current methods. Today, he was questioned on his findings.

Professor Torero, a professor of civil engineering at University College London with significant international experience and recognition in the fire safety field, also criticised the primary test method for facades in the UK regulatory system, saying it does not provide “any meaningful measure” for real-world fire performance.

His evidence came a month after the government officially confirmed that it does not plan to implement key recommendations on evacuation from phase one of the inquiry, including that personal emergency evacuation plans (PEEPs) should be created for disabled people and those with limited mobility in high-rise residential blocks.

The Home Office said implementing PEEPs would not be proportionate. Instead, it plans to continue to place its faith in the stay put advice for most buildings.

Today Professor Torero was asked about international fire safety regulations in comparison with the UK, with a focus on the US, Dubai and Australia.

The inquiry heard that both Dubai and Australia took action in response to the Grenfell Tower fire, while the US already has very “rigid” fire safety regulations in place.

It also heard that the US does not have a presumption of stay put and “requires some form of evacuation at all levels”, while Dubai abandoned the stay put policy with a new code of practice in 2018 following Grenfell and is now mandating an evacuation strategy, usually this is ‘phased’, meaning the building is evacuated in stages.

“Thinking about the position currently globally: how common would you say that phased evacuation approach is?” asked Kate Grange QC, counsel to the inquiry.

Professor Torero responded: “If you take high-rise buildings in general, I would say most countries will have a provision for a phased evacuation for high-rise buildings.

“In countries like the UK, that provision will exist for office buildings but not for residential.

“But I think to a great majority, you will have a provision for a staged evacuation also in residential buildings around the world.”

“So to what extent is this jurisdiction an outlier, at the moment, in retaining a stay put strategy?” asked Ms Grange.

“I think the UK is an outlier in the sense of its rigidity. So there is no alternative – in that sense it is truly an outlier. Even in countries where they have retained a significant number of situations in which stay put is acceptable, they will have a provision that in case it’s not, you can move it to a plan B,” replied Professor Torero.

He added: “I will say that where the UK is truly an outlier is in the absence of alternative provisions.”

Professor Torero also said: “This is a matter that deserves rigorous analysis, because I still haven’t found any reason why a stay put strategy is beneficial or necessary. There is no technical reason for that.”

On the argument that a full evacuation could be dangerous, he said: “I don’t believe that there is enough information that points in that direction when 90% of the world does it on a regular basis.”

The inquiry heard that though each US state has its own regulations, a national body called the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) “exercised huge influence” in the way that fire safety is implemented across the country.

It heard that the US follows higher standards of fire safety, including through use of sprinklers, phased evacuations and putting two staircases in buildings.

“As opposed to the UK where you have the prevalence of functional requirements… in the United States you do have the option for performance-based design, but the primary means of delivering fire safety is a very strong and strict and prescriptive regime,” Professor Torero said.

He said the codes followed in the US are “effectively prescriptive codes with an option of minor departures”. He agreed

he US has a similar large-scale fire test – NFPA 285 – to the one in the UK: BS 8414.

In a submission to the inquiry about the regulatory system in the US, the NFPA said: “[The NFPA 285] test is similar to BS 8414 and is mandated for use predominantly on high-rise buildings where a combustible component may make up part of the building’s exterior wall assembly.

“Having a rigorous test is not enough to control the fire risk. It’s important to ensure that what is specified as well as installed is the same as what is tested.”

When questioned, Professor Torero agreed that the NFPA 285 was not the best way to assess external facade fire performance.

“A test is a test. A test provides you with information, but as a criteria that serves for acceptance, the only thing it does is it cuts a tail. It doesn’t provide you with a robust methodology for acceptance,” he said, agreeing that this means the only thing the test does is exclude the worst-performing systems.

He said you are left with systems “which could be potentially very bad, but nevertheless are capable of passing the test”.

“The only thing you can say at the end when you apply those tests is that if it fails the tests, it is absolutely terrible,” Professor Torero stated.

He said earlier that the NFPA 285 was used in an otherwise “rigid” system in the US, whereas in the UK, the test is open to interpretation.

“If you have a complicated situation that has multiple variables and you’re incorporating that into a system that allows multiple solutions, the possibility of making a mistake is enormous,” Professor Torero explained.

The NFPA said its submission: “The US are faced with many of the same challenges as the UK when it comes to fire safety of high-rise buildings.

“Both countries have responded to the challenge through regulatory requirements, including use of facade fire testing. Some of the biggest differences may be found in the enforcement of the requirements.”

Professor Torero said he agreed with this.

Earlier in the day, the inquiry heard the conclusion of evidence from Professor Luke Bisby, who previously told the inquiry that UK government policy had “perpetuated and encouraged” guidance being “misapplied and exploited in the service of generating profit while avoiding liability”.

Today he was asked about the process of desktop studies – the method by which test evidence is interpreted to assess the compliance of a system that differed from the one tested.

Professor Bisby said he believed the UK system permitted the desktop studies, because any test evidence required assessment from a competent professional in order to interpret how it would operate in the real world.

But he expressed concern about the competency of some of those who carried out the assessments.

Asked to comment on one such assessment, carried out by consultancy H+H Fire, which justified the use of the cladding product used on Grenfell Tower on a different building, Professor Bisby said it was “particularly upsetting”.

“It highlighted some of the misconceptions that this inquiry has been dealing with,” he said. “I don’t use the word incompetent lightly, but it’s, from my perspective, it’s an utterly incompetent report.”

Professor Bisby raised significant concerns about the government’s new guidance to risk assessors who will examine the safety of building facades: PAS 9980.

His report said the document “neither clearly defines what is meant by competent, nor provides much assistance in terms of how this competence should be assessed, verified, maintained, controlled or monitored across the sector”.

He added that it “does little to raise the bar of the cladding fire risk assessment community and instead offers a formulaic methodology for undertaking such assessments”.

“I also believe that it should be recognised that the existence of PAS 9980 could perhaps counterintuitively generate risk that fire risk assessors who lack the requisite competence might be given a false sense of competence and might, therefore, use PAS 9980 to undertake cladding fire risk assessments they or their professional indemnity insurance might otherwise refuse,” Professor Bisby said.

“I think what it does is it helps people to feel that they have the competence, when in reality they don’t, and that’s why I think it’s dangerous,” he added.

The inquiry continues with further evidence from Professor Torero tomorrow.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters