You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Manager at Grenfell sub-contractor offered ‘very nice meal’ after deal for deadly cladding secured

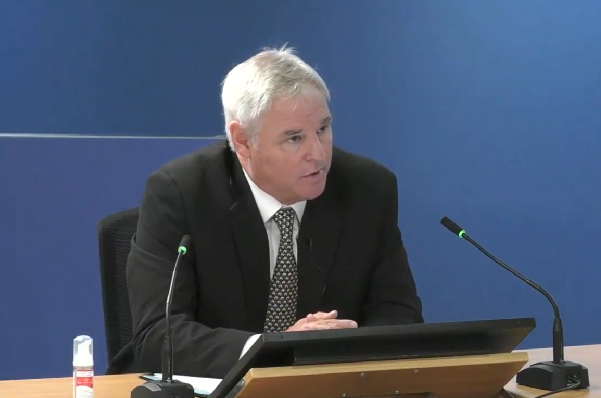

The commercial manager at the cladding sub-contractor employed on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment today denied promoting the deadly cladding due to a "cosy" relationship with supplier as emails revealed he was offered "very nice meal" after the deal was secured.

Documents were disclosed today which showed that Mark Harris of Harley Facades presented only Reynobond cladding panels made by the company Arconic to the architects as they searched for a suitable material in autumn 2013.

After Reynobond was selected as the material for the tower’s walls, Debbie French, UK sales manager at Arconic, thanked him for his “hard work and perseverance in putting Reynobond forward” and promised “lunch or dinner at some point”.

Geof Blades, sales director at CEP (which would cut and sell on the panels for the tower), who Mr Harris also emailed, promised “you will be taken out for a very nice meal very soon somewhere very nice”.

Mr Harris became aware of the Grenfell Tower project in March 2013 when he noticed the job through trawling planning websites.

His job was to secure contracts for Harley, for which he was paid commission amounting to 1% of the total contract value – in this instance £26,000.

He then emailed Bruce Sounes, the lead architect, in April to express an interest in working on it, saying “over-cladding tower blocks is very much what we do”.

Mr Sounes, who had selected zinc cladding for the tower due its appearance, eventually met with Mr Harris and Ray Bailey, managing director of Harley, in central London in late September 2013.

At this meeting Mr Harris showed several other projects Harley had carried out featuring aluminium composite material (ACM).

Mr Sounes later wrote in an email: “Their [Harley’s] recurring experience is that budgets force clients to adopt the cheapest option: ACM face-fixed [a reference to the method of attaching it to the tower].”

In October, Mr Sounes emailed Mr Harris asking him to provide budget options for various cladding types, particularly NedZinc, which he said “could be ideal”.

But when Mr Harris pulled together these options, he included only Reynobond cladding panels.

“I’m suggesting to you that the reason you didn’t [include others] was because your strong preference was for Reynobond to the exclusion of any other product,” said Richard Millett QC, counsel to the inquiry.

“I don’t agree with that,” replied Mr Harris. “This is at budget stage and we were just offering some options.”

Weeks later, he was asked to get costings for another zinc alternative, this time produced by a firm called KME. He was given a quote of £115 per sq m by this firm, but gave the architects a quote of £282 per sq m, adding in costs for delivery to site and fabrication. “From a Harley selfish point of view our preference would be to use ACM,” he wrote.

He said this was a “poor choice of words” but claimed it was just a fact that Harley was “used to using the product”.

When, in summer 2014, he was told that a mock-up would be built using Reynobond ACM – indicating that the product would likely be used on the tower – he emailed Ms French and Mr Blades to let them know.

“It’s getting exciting,” Ms French replied. “Thank you for your hard work and perseverance in putting Reynobond forward. I think I owe you and Geof either lunch or dinner at some point.”

Mr Millett said: “It looks like the relationship was pretty cosy, to use the colloquial expression.”

Mr Harris insisted it was merely “professional”.

Mr Millett asked: “Were any incentives provided for you to use Alcoa and their Reynobond product over any other product made by other manufacturers?”

Mr Harris replied: “No.”

Asked if the firm was “influential” in the selection of the ACM, Mr Harris said: “No. I think we were part of a process… If the specification for zinc had held then the contract value would have been much higher.

“There’s no interest to Harley in having a much lesser contract value – it was the client budget that drove it away from that so we were just being helpful.”

He was later asked if this “preference” for Reynobond led the firm not to promote the use of a non-combustible Rockwool system when the rival firm made an approach. Mr Harris insisted this was “not connected”.

In the afternoon session, further emails were disclosed that appeared to show Mr Harris assisting Rydon with its bid for the work when it was publicly tendered in early 2014.

He told the firm he had offered only “basic” information to other bidders when asked but “would be pleased to do so for your good self”.

He then tipped off the firm that one of the bidders, Keepmoat, had dropped out.

Mr Millett asked whether Mr Harris was “doing everything he could to help Rydon win the contract” and suggested he was acting as a “self-appointed spy” for the firm.

“I was doing everything I could to help Rydon. If they went away and won the job then great, but I was doing my job, sir, to help Rydon,” Mr Harris responded.

He was also asked about the fact that Harley worked under only a ‘letter of intent’ to appoint Rydon, and was never given a formal contract for the £2.6m job.

Asked if this was usual, he said: “No, not as a rule… It really depends on who you are dealing with and how far you can go on trust.”

Later in the day, Mr Harris was asked about the ‘value engineering’ process, by which the cost of the project was reduced by almost £1m.

He said budget pressures were the primary reason ACM was selected, and added: “Anybody in the industry will know what [value engineering] is supposed to mean and what it means in reality. Because as a sub-contractor when someone talks to you about value engineering it means a reduction in price.”

The inquiry continues next week with further witnesses from Harley Facades.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters