LFB training of control room staff ‘ad hoc and not robustly planned’ despite warnings, inquiry hears

Training of London Fire Brigade (LFB) control room operators before the Grenfell Tower fire was “ad hoc” and not planned in an “appropriate and robust manner” despite several warnings that it needed to be improved, the inquiry into the fire heard today.

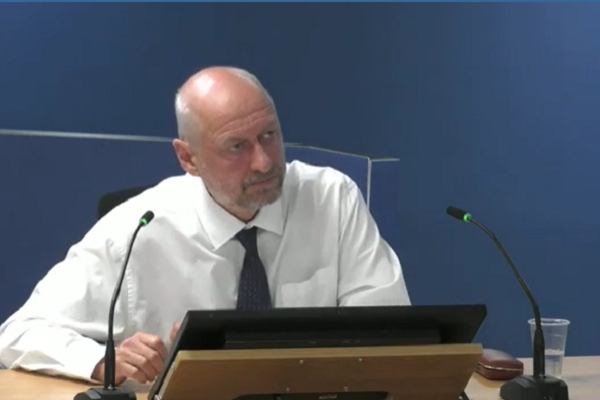

Scott Hayward, the former operations room manager at the LFB, who was in charge of the day-to-day operations of its control room since 2006, was today grilled about the training given to staff on taking calls from residents trapped by the fire.

These calls – known within the fire services as fire survival guidance (FSG) calls – are a crucial element of the inquiry’s investigation of the LFB’s preparation for Grenfell.

The inquiry’s report into the night of the fire found “serious shortcomings” within the control room – including failing to tell residents affected by fire to leave and offering assurances that they would be rescued, which “lulled [residents] into a false sense of security”.

These failures, which the report said were “systemic in nature”, came despite the Lakanal House fire in south London in 2009, in which six residents were killed after being advised to stay put.

Today Mr Hayward was asked about a report from August 2010 which warned that “adequate long-term planning” of training needs for control room staff was “not being carried out”.

“It is vitally important that adequate training planning systems are implemented for all courses, including appropriate training records that support the cyclical training planning process,” the report said.

However, a further meeting note from July 2012 showed a senior officer expressing concern that there was “nothing showing that control [staff] had carried out any form of training” and calling for the implementation of a “training matrix” to ensure this was addressed.

He warned there would be “no robust defence if anything happens in control”.

“On the face of it, it looks as if [the senior officer] is recognising that control is exposed to criticism if anything went wrong during an incident?” said counsel to the inquiry Richard Millett QC.

Mr Hayward said he could not recall the meeting in which this comment was made.

The request for a training matrix was also included in an action plan meant to address the lessons arising from the Lakanal House fire, published in January 2013.

Mr Hayward could not recall whether such a matrix was ever put in place, and cited “competing priorities” when asked why it might have been overlooked. This included a major transfer of IT systems, which itself created a requirement for training.

But in July 2016 – almost six years after the original report – a “root and branch” review of the control room raised similar concerns, noting that “some staff feel that they are not adequately developed in role”.

It added: “The reviewer has identified that maintenance of skills training is ad hoc, not planned in a robust manner, and often not recorded on an individual’s training records.”

“Is the reality from what you’ve just told us this morning so far that by July 2016, six years or so after [the] recommendations in August 2010… training was still ad hoc and not being planned in an appropriate and robust manner?” Mr Millett asked.

“I would agree with some of that,” Mr Hayward replied. “I still think that the competing issues that were going on over that period of time hindered that work. The fact that we were not part of the LFB training regime hindered that. We didn’t have the technology to be able to have a more robust system in place.”

He explained that training in the control room took place when staff were on shift. They would go off the phones to attend courses and would be called back to work if it became busy.

He said he did not have “spare staff” to book in extra cover to adequately cover the control room while staff attended training.

The inquiry heard that the general number of control room operators per shift was reduced from 24 to 16 in 2011, with a minimum of 11.

The LFB had introduced a specific policy (coded Policy No. 790) in November 2011, which sought to address the issue of FSG calls following the Lakanal House fire.

But Mr Hayward said in his witness statement that “there was not a formal presentation” to deliver this policy, and that staff were instead told about it by managers in small groups or at their desks.

“Is it right looking at that, that training was really more of an informal discussion?” asked Mr Millett.

“It wouldn’t have been a two-hour session necessarily, it would have been talking through the policy, and making sure that staff understood it,” Mr Hayward replied.

“Why didn’t you yourself personally ensure that they were given formal training?” asked Mr Millett.

“I don’t recall,” Mr Hayward said.

Mr Hayward was also asked about a national policy – 54/2004 – which provided guidance to control rooms on how to respond to FSG calls and recommended the adoption of a three-stage process. Mr Hayward said this policy was not picked up in London.

“Why did the LFB think that it was acceptable not to use the national guidance? What was different about London?” asked Mr Millett.

“I don’t know. That was just the way we looked at it. We didn’t dismiss it but it didn’t enhance or improve the analysis,” he replied.

Ahead of the Lakanal House inquests in 2013, the LFB had carried out an internal ‘gap analysis’ to identify any gaps in its local policies on FSG calls.

This work identified some gaps in national policy that were put in a draft letter to central government – namely then chief fire and rescue advisor Sir Ken Knight – in February 2012. This letter suggested that national policies were “worthy of review”.

However, minutes from a November 2012 note said that “this letter will no longer be sent”.

“Did you ask why it wasn’t sent?” asked Mr Millett.

“Yeah, and there was no answer given,” Mr Hayward replied. “The decision was made by the commissioner, and that was that.”

The inquiry continues, with further evidence from Mr Hayward tomorrow.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters