KCTMO health and safety lead claims failure to deal with fire risk assessment actions was ‘out of her control’

The former head of health and safety at the organisation that managed Grenfell Tower has told the inquiry that its failure to deal with a huge backlog of fire risk assessment actions was “out of my control”.

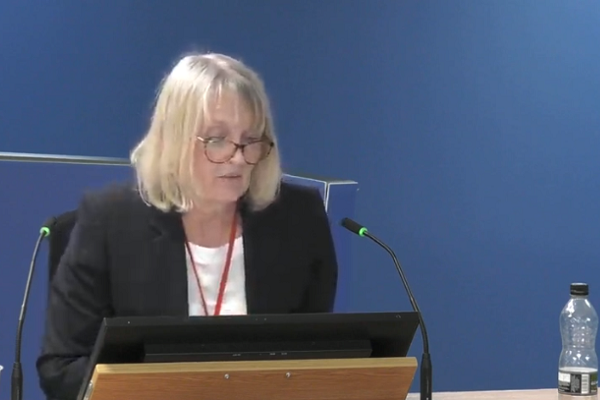

Janice Wray, who held a senior role in health and safety affairs at Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO) from its formation in 1996, was grilled today about its failure to stay on top of the actions identified as necessary in fire risk assessments.

The inquiry has already heard that the organisation had built up a substantial backlog of 1,400 actions by 2014 and had hundreds still outstanding at the time of the Grenfell Tower fire, despite persistent efforts to reduce it.

She claimed that the responsibility to complete the actions was “out of [her] control”.

She said: “I was chasing people and meeting the team leaders… and escalating further up the organisation and I just sometimes felt things were still not moving as swiftly as they should. So it’s the frustration that it’s out of my control yet I really need to try and achieve it.”

Ms Wray said that a major reason for the backlog developing was difficulties in getting external contractors to carry out the works.

“Sometimes, contractors were getting towards the end of their contract, and were a bit disinterested, and it was quite challenging to get them to do what they were required to do by the contract,” she said.

“They sound like excuses rather than reasons,” said Richard Millett, lead counsel to the inquiry.

“Well, I can only tell you what I was told,” she replied.

The inquiry has previously heard that the organisation had a maintenance contract with Connaught, before it went bust and was replaced with Morrison, which was in turn replaced with an in-house operation, Repairs Direct, in 2012.

Following negative comments in an audit of its health and safety performance by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC), KCTMO commissioned consultant Matt Hodgson to review its policies in 2013.

He made several recommendations, including the introduction of a system to monitor and track the closure of fire risk assessment actions. But there is no evidence that it changed its approach following this report.

Asked why not, Ms Wray said: “I can only reiterate that I think we became more rigorous about what we had in place.”

“Did you ask for more resources either in personnel or money terms?” Mr Millett asked.

“I suspect not because there wasn’t any more money to be had,” she replied.

Presenting figures showing that more than 800 actions remained outstanding by September 2015, Mr Millett asked: “Given that Matt Hodgson had raised this problem in the summer of 2013, how could it come about that two years later such a significant proportion of [fire risk assessment] actions remained outstanding?”

“You appreciate that my role was to allocate and chase and do everything I can, but it clearly wasn’t enough… I can’t give you chapter and verse as to why these things weren’t happening,” Ms Wray said.

Despite consistent reference to this issue in meetings of senior staff members at KCTMO, the figures Ms Wray produced at this stage only showed the overall number of actions outstanding, not how long they had been out of date for.

Other managers requested this breakdown, but it was not provided.

“The problem with this data at this stage is you can’t see which actions have gone past their due date, nor can you see which risk priority they have. Why is that critical data missing, particularly given that it had been requested for months?” Mr Millett asked.

“I can’t give you an explanation other than time, that actually it took longer than you think it did to produce it so I produced what I could,” Ms Wray replied.

She was grilled in detail about comments made by her colleague Peter Maddison, which appeared to show him seeking to re-categorise the priority of the actions identified in the risk assessments in order to help reduce the backlog.

In one instance in July 2014, he was recorded as asking Ms Wray to clarify which actions could be defined as “absolute requirements” and which could be considered “best practice”.

Mr Millett asked: “Was the truth of it that he was trying to get you to say that those marked red [indicating top priority] by Carl Stokes [the risk assessor for KCTMO] were not really red, or at least were a lighter shade of red?”

“I don’t believe so and I was the one controlling the process, so they wouldn’t have been re-designated,” she said.

Asked specifically about fire risk assessments carried out on Grenfell Tower, the inquiry heard that 42 items identified in April 2016 were still outstanding by the time of a follow-up assessment in June 2016. Of these, 39 were high priority, meaning they should have been rectified in three weeks.

“How come so many of these items had not been addressed?” Mr Millett asked.

Ms Wray said that she “could not give an explanation” without looking at the detail, but that some of the issues may have related to documentation and assurances which could only be provided at the end of the tower’s refurbishment.

One request, to install operating instructions next to the tower’s smoke ventilation system, was not dealt with until late August.

“Why did you consider it was appropriate to leave items such as that without taking action for some four months?” asked Mr Millett.

“I wouldn’t have taken no action at all, I would have chased up Claire [Williams, project manager for the refurbishment] repeatedly in the interim,” she said.

Ms Wray will continue to give evidence tomorrow.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters