You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Increase grant to curb rise in housing benefit spending, CIH recommends

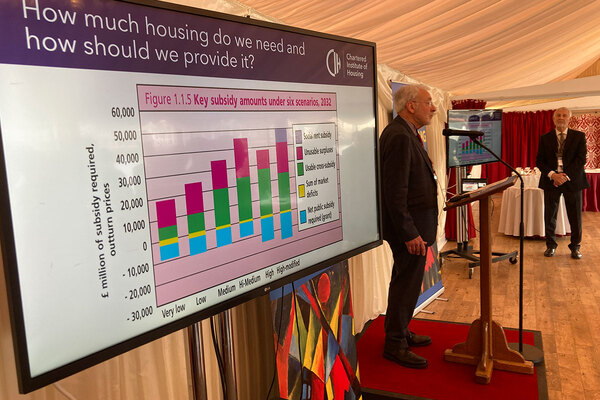

The government should increase supply-side grants for new homes to curb rising spending on housing benefit, a report from the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) has recommended.

An essay by economist Ralph Mould in the CIH’s 2024 UK Housing Review noted that despite “repeated government efforts to control costs”, housing benefit spending is now at its highest-ever relative level.

Meanwhile, over the past four decades, relative government spending on supply-side grants for social housebuilding has reduced.

The paper said there is a “strong case” for shifting subsidies back towards the supply side, given the “significant housing need across the UK”, which is placing “growing pressure” on the benefits system.

According to the CIH, total government spending on housing subsidy was £30.5bn in 2021-22. When adjusted to 2022 prices, this figure is “not dissimilar” to spending in earlier decades: £32.6bn in 1985-86 and £26bn in 1975-76.

However, within those figures, the share of “demand” subsidy rose dramatically from 18% in the 1970s to 67% in the 1980s and 88% in 2020-21.

This shift in spending from mostly supply-side to mostly demand-side subsidies was “largely by design”, Mr Mould said. Demand subsidy “tends to be more flexible” and “adjusts to people’s circumstances”; unlike a social home, it can be withdrawn when a recipient is earning more and no longer requires it.

While “there is a case” for this approach “when the supply side is working”, Mr Mould said, rising housing benefit spending now reflects growing pressure on the overall housing system, with more than 1.5 million households on waiting lists for social housing.

The report said: “Previous attempts to reduce expenditure on demand subsidies directly have been unsuccessful. To keep overall housing subsidies in the UK stable – or to reduce them – supply subsidies will need to be increased in order to achieve long-term savings on the demand side.”

Historically, the Treasury has been reluctant to accept the case for more spending on grants for social housebuilding, due to the high capital costs compared to social rents and housing benefit.

For the Treasury to see ‘cashable savings’, yields in the social rented sector would need to rise and borrowing rates for housing associations would need to fall, enabling them to borrow more so less government subsidy is needed per home. “While this shift could eventually occur, it seems unlikely in the immediate term,” Mr Mould noted.

Another issue is that the UK currently treats capital grants as a cost, rather than an investment in a public asset on the country’s balance sheet. A re-evaluation of the UK’s fiscal rules, as chancellor Rachel Reeves is reportedly considering before the Autumn Budget on 30 October, could encourage more investment in housing by “recognising its long-term economic returns”.

Mr Mould noted that the UK has gained £9.4bn in current prices over the past decade from Right to Buy receipts, “in no small part due to the historic investments in social housing”. Meanwhile, the value of housing stock within local authorities’ Housing Revenue Accounts was around £122bn in 2022.

“A more holistic approach to valuing social housing investments – recognising both their downstream savings to the Exchequer as well as their value as a national asset – would go a long way in making the case for increased investment in the supply side,” Mr Mould concluded.

A Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government spokesperson said: “This government will deliver the biggest boost to social and affordable housebuilding in a generation and will set out details of future investment at the next Spending Review.

“This will give councils and housing associations the stability they need to be able to borrow and invest in both new and existing homes, while also ensuring that there are protections for existing and future social housing tenants.”

Last week, research by Savills, the National Housing Federation and the Home Builders Federation warned that Labour is on course to miss its housebuilding target by up to 475,000 homes without more grant funding for social housing.

This is because private homes are built to meet “demand”, ie at the rate homes can be sold to make a profit, while affordable and social homes meet underlying housing need, meaning they can be “absorbed much more quickly” by local housing markets.

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters