You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

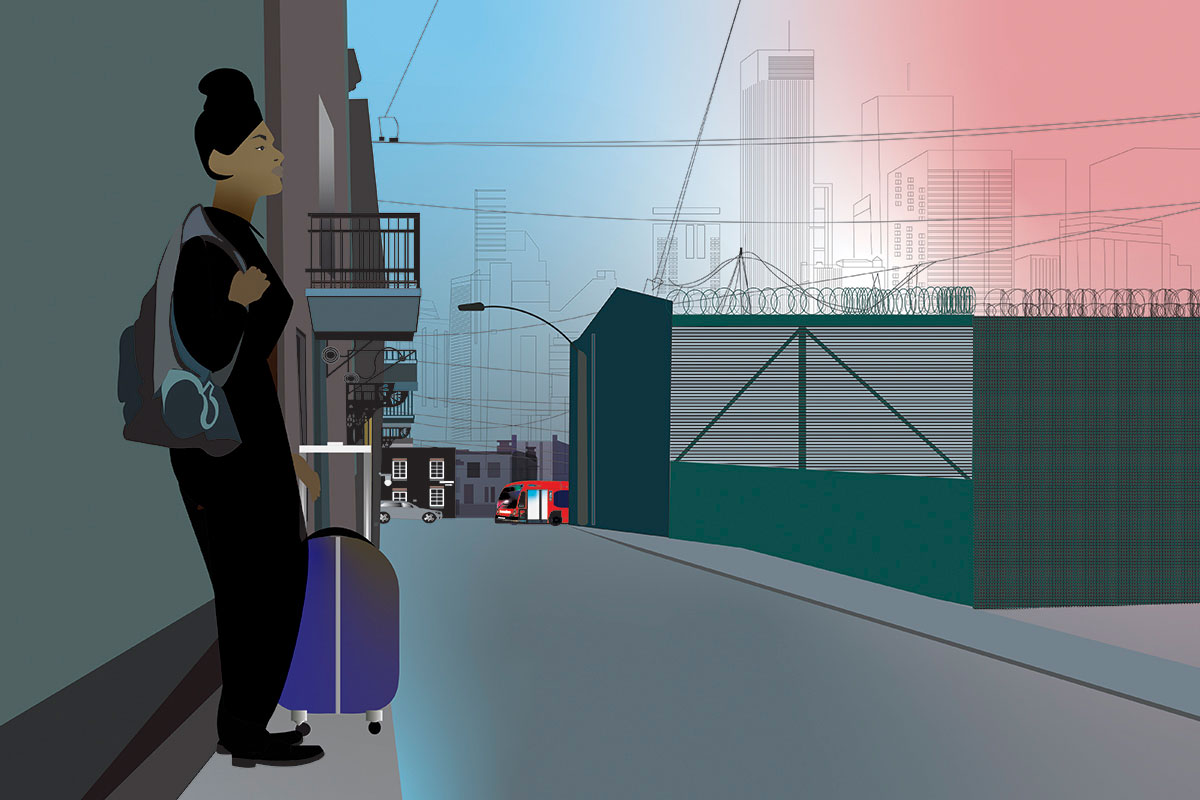

Without somewhere safe to go, women leaving prison ‘do not stand a chance’

Access to affordable housing is a problem for both the prison service and women who have been released from a custodial sentence. Why has so little been done to solve this, and are there approaches that could lead to change? Cherry Casey reports. Illustration by Judith Rudd

In her 2007 review of women with particular vulnerabilities in the criminal justice system, Labour peer and former barrister Baroness Corston deemed the pathway to accommodation after release from prison to be in urgent need of “speedy, fundamental, gender-specific reform”. Fourteen years on, however, women are still leaving prison with nowhere safe to go at astonishing rates: 62%, according to figures released by Safe Homes for Women Leaving Prison (SHWLP) in 2020.

Without secure housing lined up, as soon as they are “through the gate”, these women – many of whom are the most vulnerable in society – “do not stand a chance”, says Dr Jenny Earle, an advisor to SHWLP. Homelessness presents a barrier to rehabilitation.

“You cannot sign up with a GP; you cannot get your kids back; you cannot get a job; you cannot enroll in longer-term mental health and drug and alcohol support,” she says.

“The number [of women leaving prison] in any one borough is small, but the ripple effect of not addressing that woman’s housing needs is very significant in terms of children, health needs, anti-social behaviour and reoffending”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reoffending rate of men and women without settled accommodation is 65%.[2]

So why, given that Baroness Corston’s recommendation was so long ago and initiatives such as the Homelessness Reduction Act and Female Offender Strategy have since been introduced, has the housing problem not been solved?

One reason, says Dr Earle, is the “failure to really factor in the distinct issues involved in the housing needs of women”.

Women are more likely to be at risk of domestic and sexual abuse; to have been in care as a child and therefore lacking family support; to have significant physical and mental health issues deriving from past trauma; and to be primary carers of children. All these factors play a part in creating complex housing needs.

Women’s prison release protocol

Women are also more likely to experience ‘hidden homelessness’: choosing options such as sofa-surfing or exchanging sex for a roof over their heads to avoid the dangers of sleeping rough. This makes it hard to know the true scale of the problem.

And since recent reform of the probation system, one pressing issue is “a lack of understanding across the board about who is actually responsible when a woman leaves prison and doesn’t have a safe home to go to”, says Dr Kate Paradine, chief executive of the charity Women in Prison. “We need to understand what the prison should be doing, what the probation officer should be doing, what the local authority that the woman is due to be released into should be doing, and what third-sector organisations need to be doing.”

This urgent need to get a grip on the situation is one reason why SHWLP commissioned research and policy consultant Katy Swaine Williams to create the women’s prison release protocol. Created via consultation with criminal justice agencies, specialist women’s services and local authorities, the protocol sets out how and why relevant agencies must engage in more effective, consistent joined-up working.

“There is no point trying to address a woman’s housing needs on the day of release and thinking that there will be a good result”

However, its primary task is to be “a vehicle to promote better practice by local authorities in how they respond to applications for housing for women leaving prison”, says Ms Swaine Williams. Its example of best practice is the approach used by Lambeth Council – one SHWLP hopes other London local authorities will replicate.

“The number [of women leaving prison] in any one borough is small, but the ripple effect of not addressing that woman’s housing needs is very significant in terms of children, health needs, anti-social behaviour and reoffending,” says Dr Earle. “All those things that evidence shows come from a lack of suitable, safe accommodation can be nipped in the bud if you provide proper housing, and I think Lambeth understands that.”

Lambeth’s successful model – which has been recognised by government, too – is in large part due to its appointment of a prison release navigator (PRN) in 2019. This person works alongside the single persons’ housing advisor and their role is to “identify the barriers to people leaving prison going into accommodation and trying to overcome them”, says Maria Kay, cabinet member for housing and homelessness. This includes, for instance, an identification letter pilot scheme, to overcome the reoccurring issue of a woman lacking the necessary documents to apply for housing.

Another issue is timing. As Dr Earle explains: “There is no point trying to address a woman’s housing needs on the day of release and thinking that there will be a good result.”

Improving referrals

As well as aiming to carry out housing interviews while women are still in custody, Lambeth’s PRN “has been working with prison services and probation to improve the referral process so that they can be received in a timely way and with the required information”, says Ms Kay. “This means the woman will not have to keep repeating information and it allows time to carry out the background checks required for housing assessments.”

“In the vast majority of cases, women who are leaving prison primarily need an advocate who can support them in making a case for the housing and other services they need, then supporting them in keeping that housing”

Having a PRN also means there is the flexibility needed to work on complex cases. For instance, when an individual went missing after leaving prison, the PRN was able to work with relevant services to find her and connect her with secure accommodation.

And for a woman who has had contact with the criminal justice system and is now dealing with the complexities of finding housing, having a single point of contact is also important, says Ms Kay.

Essentially, the PRN role is effective because it advocates on behalf of vulnerable women, which, Dr Paradine says, is vital. “Often, women have got into this position partly because they haven’t been able to advocate for themselves… But in the vast majority of cases, women who are leaving prison primarily need an advocate who can support them in making a case for the housing and other services they need, then supporting them in keeping that housing. That advocacy isn’t invested in properly.”

Intentional homelessness

One particularly problematic barrier is the issue of becoming ‘intentionally homeless’ via, for instance, not paying rent in the past. But as Tilly-Mae Townsend, who was released from prison in 2020 and is now a resident of Housing for Women’s ReConnect project explains, the threat of intentional homelessness can present a catch-22 situation.

“Prior to going into prison, I lived in temporary accommodation for two years, given to me by Southwark Council. My rent was £1,200 a month and I couldn’t afford it. Housing benefit didn’t cover it, so I had no choice but to find ways to make money, because if I had got myself evicted for rent arrears, Southwark Council would have deemed me intentionally homeless and not allowed me to access further housing support within the borough. Unfortunately, the activities I engaged in to make the extra money led to me going to prison,” she says.

“We’re going to entrench the already shocking reoffending and recall rate. We are setting people up to fail”

Lambeth’s PRN, however, can and has successfully challenged housing providers that were previously unwilling to take on an individual on the grounds of intentional homelessness. They can also negotiate incentives with private landlords, if this pathway is considered most appropriate.

With in-prison housing support having “fallen into a hole” since the recent reunification of probation services, says Dr Earle, the publication of the prison release protocol could not be more timely. But if its illustration of how and why Lambeth’s model must be adopted more broadly is to get off the ground, it too needs advocacy.

“The problem is not vast in scale, but it is a bit complicated,” says Dr Earle. “Why doesn’t [the government] seize our protocol? We’re doing everything we can to show them what needs to be done but it needs senior leadership and joined-up working.”

It is hoped Sophie Linden, London’s deputy mayor for policing and crime, will provide that senior leadership. The protocol has been sent to her with a request that she and the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime promote implementation across London boroughs.

Dr Paradine says: “We could address this problem if there was sufficient will put towards it, if national government prioritised building truly affordable homes over more prison places and if each local authority was committed to addressing the problem of the small number of women released into their area.”

Without this, she warns: “We’re going to entrench the already shocking reoffending and recall rate. We are setting people up to fail.”

Sign up for our care and support newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters