You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Where did the stay put policy come from and where do we go now?

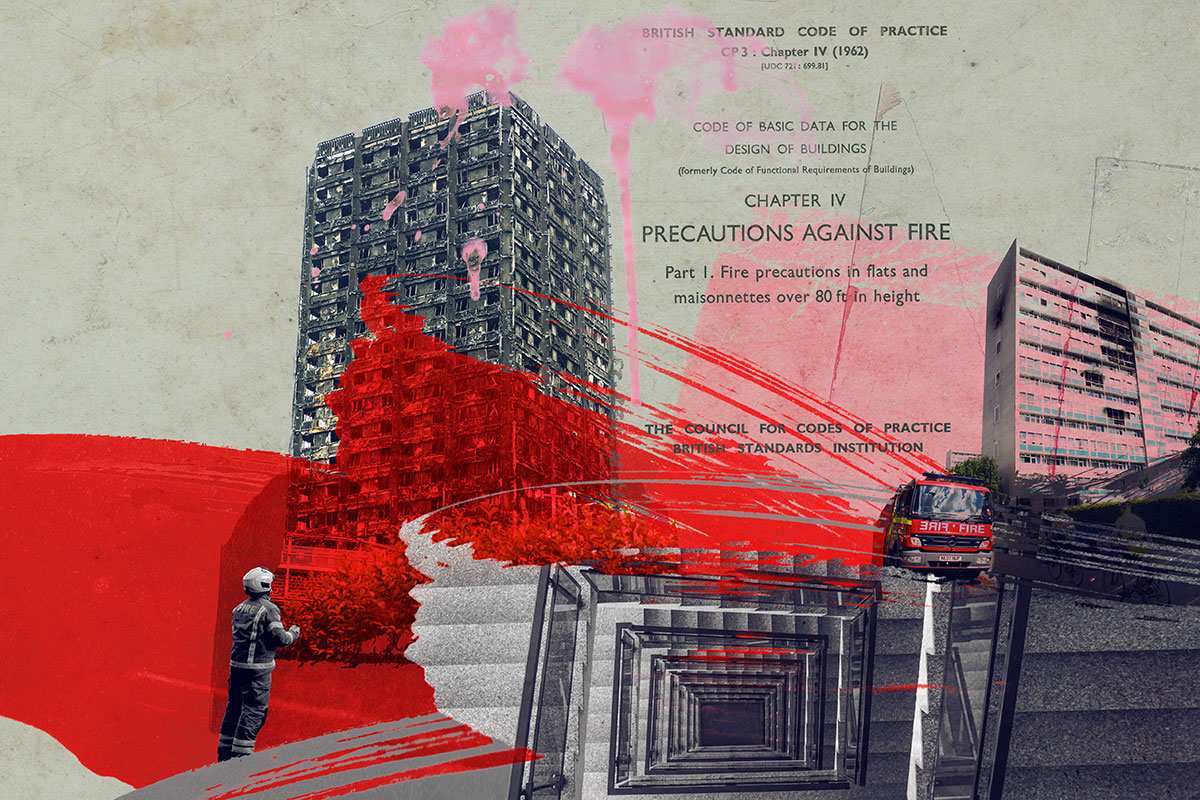

“Stay put had become an article of faith and to depart from it was unthinkable.” These are the words of Grenfell Inquiry judge Sir Martin Moore-Bick. Peter Apps looks at where the idea came from and where we go now. Illustration by Michelle Thompson

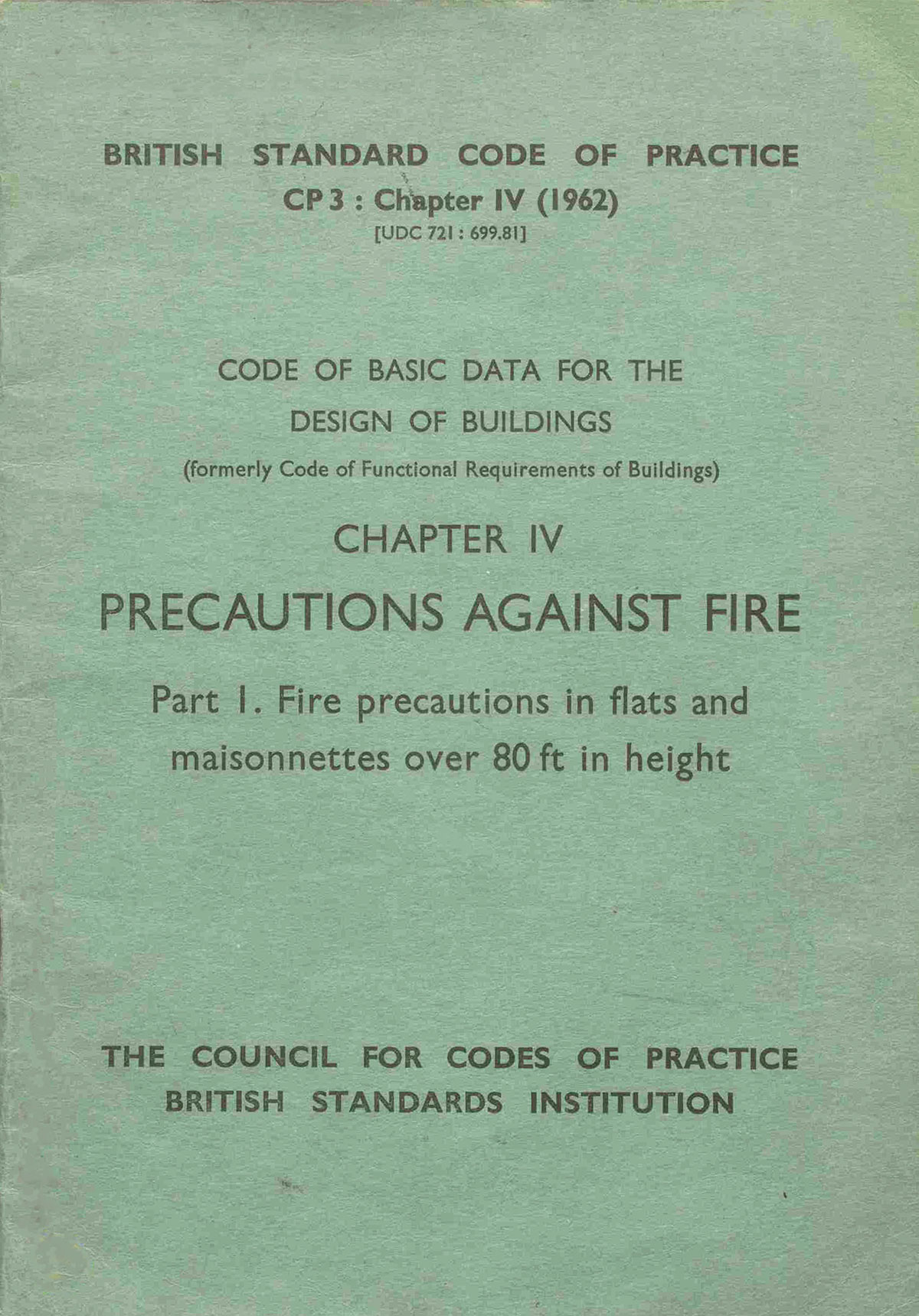

The idea of ‘stay put’ developed in the UK in the early 1960s. British Standard Code of Practice 1962 was introduced as the first national standard for tall residential buildings. It required all blocks taller than 80 feet to provide one hour’s fire resistance to enable firefighters to battle flames inside the building.

The aim of the code was to ensure that each flat in a building would act as an individual compartment that would contain any fire for at least an hour. This principle of ‘compartmentation’ would enable firefighters to put out one fire in one flat rather than face a whole building ablaze.

But to work, the principle has two key requirements. First, the building must have the necessary ‘passive fire protection’ to withstand the spread of flames. Second, access to the building must be clear enough that affected residents can escape and firefighters can get in quickly.

Partly because of this second requirement, the code considered fire alarms to be undesirable. The fear is that they could trigger unnecessary evacuations that impede firefighters’ access or even put residents in danger by exposing them to smoke.

There are many advocates for stay put, who point to data that shows it is successful in the vast majority of fires. National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC) data shows that there were more than 57,000 fires in high rises between 2010 and 2017, but that only 216 (0.4%) required the evacuation of more than five residents.

“We have had 30 years of people throwing up buildings cheaply and quickly. That has created issues with fire performance that are pretty widespread”

Industry source

But this confidence was first challenged on 3 July 2009. A fire in Lakanal House, south London, spread externally and internally in a serious failure of compartmentation. It killed six people, including three children. They had all been told to ‘stay put’.

Nevertheless, after this fire, stay put remained the default strategy – the Local Government Association published a guide in 2011, commissioned by government, written by fire experts and supported across the sector, that concluded it remained the safest option.

This guide took a strong line on stay put, advising building owners to “seek a second opinion” if risk assessors felt that stay put should not be adopted until the safety of the building had been proven.

It said: “Some enforcing authorities and fire risk assessors have been adopting a precautionary approach whereby, unless it can be proven that the standard of construction is adequate for ‘stay put’, the assumption should be that it is not. As a consequence, simultaneous evacuation has sometimes been adopted, and fire alarm systems fitted retrospectively, in blocks of flats designed to support a ‘stay put’ strategy.

“This is considered unduly pessimistic. Indeed, such an approach is not justified by experience or statistical evidence from fires in blocks of flats.”

However, further guidance to fire authorities – Generic risk assessment 3.2 – published by government in 2014 did warn that stay put “may become untenable due to unexpected fire spread”. It added that “if necessary”, building owners should “have a suitable emergency evacuation plan”.

The fire service faced heavy criticism in Grenfell Inquiry chair Sir Martin Moore-Bick’s report for not acting on this guidance. But, the truth is that the responsibility for developing a specific evacuation plan lay with the building owners, and in accordance with the official advice, most high rises owners did not create one.

Only a small percentage of fires in high rises spread beyond the flat of origin. But it does happen. The government says there have been 8,025 fires in buildings taller than four storeys since 2016/17. Of these, 156 affected at least two floors, with 72 affecting more than two. This is a rate of around one per week.

Why is this happening? Sometimes, it is likely to be an unavoidable consequence of the size of the fire. If a big fire bursts out of a window, ‘the Coanda effect’ means it can lick up the building and smash through the window of the floor above.

But fires also spread because compartmentation fails. Buildings now have much higher volumes of combustible materials on their external walls than they did in 1962 when stay put was established. As well as cladding, this material may include insulation systems, infill panels and balconies, all of which can provide a route up the building for a fire.

Compartmentation is also easily compromised inside a building: defective fire doors, vents, poorly installed pipes or damaged firebreaks can all enable smoke and flame to spread.

There is evidence of widespread problems with these features. Housing association Hyde conducted intrusive assessments of the fire risks in its 86 high rises, and it found problems in all of them.

One industry source says: “We have had 30 years of people throwing up buildings cheaply and quickly. That has created issues with fire performance that are pretty widespread.”

One of the concerns raised about stay put after Lakanal House was that the call handlers had applied it as a mantra. The victims were advised to stay put, even when they said smoke and flames were in their properties.

But this has never been what ‘stay put’ means. The advice is not stay put until the fire kills you – it is to stay put unless you are being affected by smoke and flame.

However, this means people must have an escape route – and that is not always a given.

High-rise residential buildings in the UK, such as Grenfell, have only one staircase. This is the result of the absence of any regulations requiring architects to include a second.

Paul Bussey, fire lead at AHMM Architects and a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Regulation and Standards Group, explains that official guidance only requires a building to have ‘alternative exits’. This has left room for interpretation.

Developers are reluctant to include second staircases in high rises. Staircases are expensive to build, remove from the ‘net lettable area’ (the parts of a building that can be sold) and act as a drag on profit margins. Developers have therefore taken the guidance to mean that a second door to a single staircase is an acceptable ‘alternative exit’.

But this creates a serious problem during a fire – firefighters will have to use the same staircase to tackle the blaze as the residents who are escaping it.

Phil Murphy, a former firefighter and a high-rise residential building management consultant, says this can be particularly dangerous if the stairway fills with smoke. This can happen due to breaches of compartmentation, but also because firefighters typically wedge open doors to the stairwell to run their hoses through. When they open the door of the flat in which the fire started, smoke will start filling the communal stairwell.

If the fire does get out of control, communication is also a problem. With no alarms, how can residents be told to get out? At Grenfell, the firefighters relied on loudhailers and 999 calls.

Now this will all change. Sir Martin has ordered government to produce national guidance on evacuations. Building owners will be required to fit alarms and develop plans to evacuate the most vulnerable residents.

There are still some who believe stay put is the right approach. Colin Todd, managing director of CS Todd & Associates, says the policy protects people who are vulnerable and unable to escape. It also avoids putting firefighters at unnecessary risk.

He says the aim needs to be to fix buildings with flawed compartmentation, not to change the fire strategy: “If you had a situation where a car doesn’t have any brakes, you would focus on fixing the brakes, not changing the way we drive.”

But others do see the need for change.

Jan Taranczuk, a fire safety consultant, suggests a new approach called ‘stay put plus’. This would mean identifying flats that are particularly vulnerable to fire and installing additional fire safety measures, such as sprinklers or misters.

In Scotland, new regulations have recently come into force that require ‘manual alarms’ in new high rises. These can be controlled from ground level or an offsite monitoring suite, to enable firefighters to partially evacuate the parts of the building at risk – or to evacuate the whole building in phases.

“If you had a situation where a car doesn’t have any brakes, you would focus on fixing the brakes, not changing the way we drive”

Colin Todd, CS Todd & Associates

There are also calls to move away from single staircases. Mr Bussey says RIBA is pushing for the government to introduce new regulations to either make second staircases mandatory in new builds or provide tax incentives to make them more attractive propositions.

But even if this was adopted, what about the hundreds of existing buildings with just one staircase?

Mr Murphy advocates a change to firefighting tactics to focus on ‘protecting the staircase’. This could involve new technology, such as smoke screens, which can cover communal doorways while hoses are run through.

Others suggest moving away from a standard approach of ‘stay put’ to a bespoke, block-by-block approach. The idea is that buildings would ‘earn’ stay put through intensive inspections of compartmentation.

For its part, a government spokesperson said: “We welcome the publication of the report from phase one of the independent public inquiry and will carefully consider its findings and recommendations in full.”

It is also worth noting that hundreds of blocks around the country have already dropped it. In May 2018, the NFCC published guidance suggesting that blocks known to have dangerous cladding adopt an evacuation strategy, backed by either a 24-hour waking watch or fire alarms.

Inside Housing recently visited one building in Plymouth that had adopted this approach. A full evacuation in an actual fire was accomplished in around 30 minutes, despite the building only having one staircase and several residents needing help to get out. Achieving this required knowledge of those residents, planning, communication and an alarm system, but it was done.

Stay put is also not global. In Australia, for example, most high rises are evacuated during fires and the installation and maintenance of alarm systems is a strict legal requirement.

Whatever the approach, it is clearly now time for change. Stay put works until it does not. Building failures may be rare, but they are no longer unheard of – and we need a plan for what to do when the next one happens. The lives of the people who live there could very well depend on it.

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry recommendations: phase one

Picture: Getty

Evacuation

There were no plans to evacuate Grenfell Tower available. Sir Martin Moore-Bick, chair of the Grenfell Inquiry, recommended:

- The development of national guidelines for carrying out partial or total evacuations of high-rise buildings – including protecting fire access routes and procedures for evacuating people who require assistance

- Fire services develop policies for partial or total evacuation of high rises

- Owner and manager be required to draw up and keep under review evacuation plans, with copies provided to local fire and rescue services and placed in an information box on the premises

- All high-rise buildings be equipped with facilities to enable the sending of an evacuation signal to the whole or a selected part of the building

- Owners and managers be required by law to prepare personal evacuation plans for residents who may struggle to do so personally, with information about them stored in the premise’s information box

- All fire services be equipped with smoke hoods to help evacuate residents down smoke-filled stairs

Fire doors

Sir Martin said it is apparent that “ineffective fire doors allowed smoke and toxic gases to spread through the building more quickly than should have been possible”, and that missing self-closers played an important role. He recommended:

- An urgent inspection of fire doors in all buildings containing separate dwellings, whether or not they are high rises

- A legal requirement on the owner or manager of these buildings to check doors at least every three months to ensure self-closing devices are working effectively

Sprinklers

Noting the recommendation from the coroner investigating the Lakanal House fire that the use of sprinklers be encouraged, Sir Martin said that some of his experts had “urged me to go a step further and to recommend such systems be installed in all existing high-rise buildings”.

He said that sprinklers have “a very effective part to play” in an overall scheme of fire safety, but that he had not yet heard evidence about their use. He said that he could make no recommendations at this stage, but that he would consider the matter in phase two.

Internal signage

Floor numbers in the tower were not clearly marked and markings were not updated when the floor numbers changed following the refurbishment. Sir Martin said that all high-rise buildings should have floors clearly marked in a prominent place, which would be visible in low light or smoky conditions. Given that not all residents of Grenfell could read fire information signs, he said this should now be provided in a means that all residents can understand.

Use of combustible materials

Sir Martin said the original fire in the kitchen was no more than an ordinary kitchen fire that spread to the cladding because of “the proximity of combustible materials to the kitchen windows” – such as the uPVC frames.

He said this is a matter that “it would be sensible” for owners of other high-rise buildings to check.

He said he would “add his voice” to those who have expressed concern about the slow pace of removal work for more than 400 other tall buildings in England with aluminium composite material cladding.

A total of 97 buildings in the social housing sector and 168 in the private sector have not yet seen the work complete. Sir Martin said the work must be completed “as vigorously as possible”.

He said particular attention should be paid to decorative features, given the crucial role played by the architectural crown at Grenfell in spreading the fire around the building.

Given the decision to ban combustible materials on new buildings last year, he did not call for further restrictions on their use.

Fire service: knowledge and understanding of materials in high-rise buildings

Sir Martin raised concern that junior firefighters were not aware of the danger of cladding fires, and that the London Fire Brigade (LFB) was unaware of the combustible materials used to refurbish Grenfell Tower.

He therefore recommended:

- That the owner and manager of every high-rise building is required to provide details of external walls and the materials used to the local fire service, and inform them of any changes

- To ensure that fire services personnel at all levels understand the risk of cladding fires

Plans

Sir Martin said that a lack of plans did not “unduly hamper” fire services at Grenfell, as each floor was laid out in the same way. However he warned that another building with a more complex layout could pose problems. He recommended:

- That owners and managers of high-rise buildings are required by law to provide paper and electronic versions of building plans of all high rises to local fire services

- To ensure the building contains a premises information box, including a copy of floor plans

Lifts

Firefighters were unable to use a mechanism that allows them to take control of the lifts on the night of the fire, hampering their progress and meaning residents could still use the lifts, “in some cases with fatal consequences”. Sir Martin therefore recommended:

- That the owner and manager of every high-rise building be required by law to carry out regular inspections of any lift required for use by firefighters and the mechanism that allows them to take control of it

Section 7(2)(d) of the Fire and Rescue Services Act

The judge was concerned that inspections of the tower by the fire service before the fire were not enough to meet their responsibilities under this act. He recommended:

- A revision of the guidance for the London Fire Brigade, and training for all officers above the rank of crew manager in inspecting high-rise buildings

Co-operation between emergency services

There was a lack of communication between each emergency service at Grenfell, with each declaring a major incident at different times without telling each other. Sir Martin recommended several changes to ensure better communication in the future.

Personal fire protection

Sir Martin decided not to issue a recommendation that individual flats be provided with fire extinguishers or fire blankets, noting concerns that this could encourage residents to fight fires rather than escape and call the emergency services.

Communication between the control room and the incident commander

While guidance calls for a “free flow” of information between a fire service control room and the commanding officer on the ground, that often does not happen. Sir Martin therefore recommended:

- A review of policies by the LFB on this matter, including training for all officers who could serve as incident commanders and senior control room officers.

- A dedicated communications link between the senior officer and the incident commander

Emergency calls

Even allowing for the pressure of the night, Sir Martin said that fire survival guidance calls were not handled in an “appropriate or effective way”. He therefore recommended:

- Amending of policies and training for control room officers

- That all fire services develop policies for multiple fire survival guidance calls

- Electronic systems to record and display calls

- A policy for managing a transition from ‘stay put’ to ‘get out’ and training for call handlers in delivering this change of advice

Command and control

Sir Martin said firefighters too frequently “acted on their own initiative”, resulting in a duplication of effort. He called for better policies to ensure:

- Better control of training and deployment

- Information is obtained from crews after they have deployed

Equipment

Sir Martin made some recommendations for improvements to fire service equipment, including radios and the command support system.

Testing and certification of materials

Sir Martin said this is an issue that will be investigated “early in phase two”, along with an assessment of “whether the current guidance on how to comply with the building regulations is sufficiently clear and reliable”.

He also said the inquiry would investigate whether a ‘prescriptive’ regime of regulation was necessary. However, as these issues have not yet been examined by the inquiry he did not make any recommendations.

Grenfell Tower Inquiry: full coverage

Evacuation plans should be developed for all high-rise buildings, says Grenfell Inquiry judge

Sir Martin calls for landlords to develop evacuation policies on all high-rise buildings as well as recommending an “urgent” inspection of fire doors in all properties.

Click here to read the full story

Grenfell Tower Inquiry: the recommendations

A full list of Sir Martin’s 17 recommendations, including calls for building owners to install facilities to give evacuation signals to tenants and cladding removal work to be completed “as vigorously as possible”.

Click here to read the full story

Grenfell Inquiry: ACM cladding was ‘primary cause of fire spread’ and tower did not comply with regulations, judge rules

The judge leading the Grenfell Tower Inquiry has ruled that the cladding installed on the tower did not comply with building regulations, finding that the polyethylene-cored panels were the “primary cause” of the rapid spread of flames.

Click here to read the full story

Grenfell Inquiry: round-up of Sir Martin Moore-Bick’s phase one conclusions

How the fire started, why the fire spread, what was the response from the fire brigade, emergency services and Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, all covered in our round-up of the Sir Martin’s conclusions.

Click here to read the full story

Grenfell Inquiry report: stay put ‘an article of faith’ within LFB

The inquiry judge criticises the London Fire Brigade’s “reluctance to believe that a building wouldn’t comply with building regulations” and claims that many lives would have been saved if the incident commander told residents to evacuate earlier.

Click here to read the full story

KCTMO chief criticised for ‘passive role’ and ‘ineffective leadership’ on night of Grenfell fire

Former chief executive of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation was labelled as “essentially detached” from events on the night of the fire by Sir Martin. The company was also criticised for not passing on crucial resident information to the fire brigade.

Click here to read the full story

Grenfell Inquiry: ACM cladding was ‘primary cause of fire spread’ and tower did not comply with regulations

Despite saying that he would try not to deal with the make-up of the building in his phase one report, Sir Martin decided to make an early finding that the building breached headline regulation. He also ruled that the building suffered “total failure of compartmentation”.

Click here to read the full story

Grenfell Inquiry reaction: survivors call for implementation timeline for recommendations

Survivors group Grenfell United calls for fire service bosses to “face consequences” for failings leading up to the fire, while the London Fire Brigade, National Housing Federation and Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea also respond

Click here to read the full story

Recommendation rejected by Pickles as ‘disproportionate’ in 2013 repeated in Grenfell Tower Inquiry

Story reveals that as communities secretary Eric Pickles was given a recommendation after the Lakanal House Fire to ensure all high-rises “provide relevant information on or near premises” but branded a move to implement “unnecessary and disproportionate”

Click here to read the full story

Grenfell judge calls for Johnson to implement Grenfell Inquiry recommendations ‘without delay’

Grenfell judge calls for Johnson to implement Grenfell Inquiry recommendations ‘without delay’ In a letter to prime minister Boris Johnson before the inquiry was published, report author, Sir Martin Moore-Bick, calls on PM to implement inquiry recommendations “without delay”.

Click here to read the full story

Government to implement Grenfell Inquiry recommendations ‘in full’ and provide funding

Robert Jenrick, housing secretary, promises to bring in all of Sir Martin’s recommendations “without delay” and also guarantees government will pay for changes.

Click here to read the full story

Government to implement Grenfell Inquiry recommendations in full

Ministers will implement recommendations put forward in the Grenfell Tower Inquiry’s first report “in full” and “without delay”, housing secretary Robert Jenrick has confirmed.

Click here to read the full story

Stay Put: where did it come from and where do we go next?

“Stay put had become an article of faith and to depart from it was unthinkable.” These are the words of Grenfell Inquiry judge Sir Martin Moore-Bick. Peter Apps looks at where the idea came from and where we go now.

Click here to read the full story

Is your approach to fire safety reliant on faith in the system or good judgement?

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry report suggests that housing providers and the fire service have not been willing enough to plan for worst-case scenario fires in high-rise buildings. Martin Hilditch outlines how the inquiry’s report should guide thinking and practice