You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

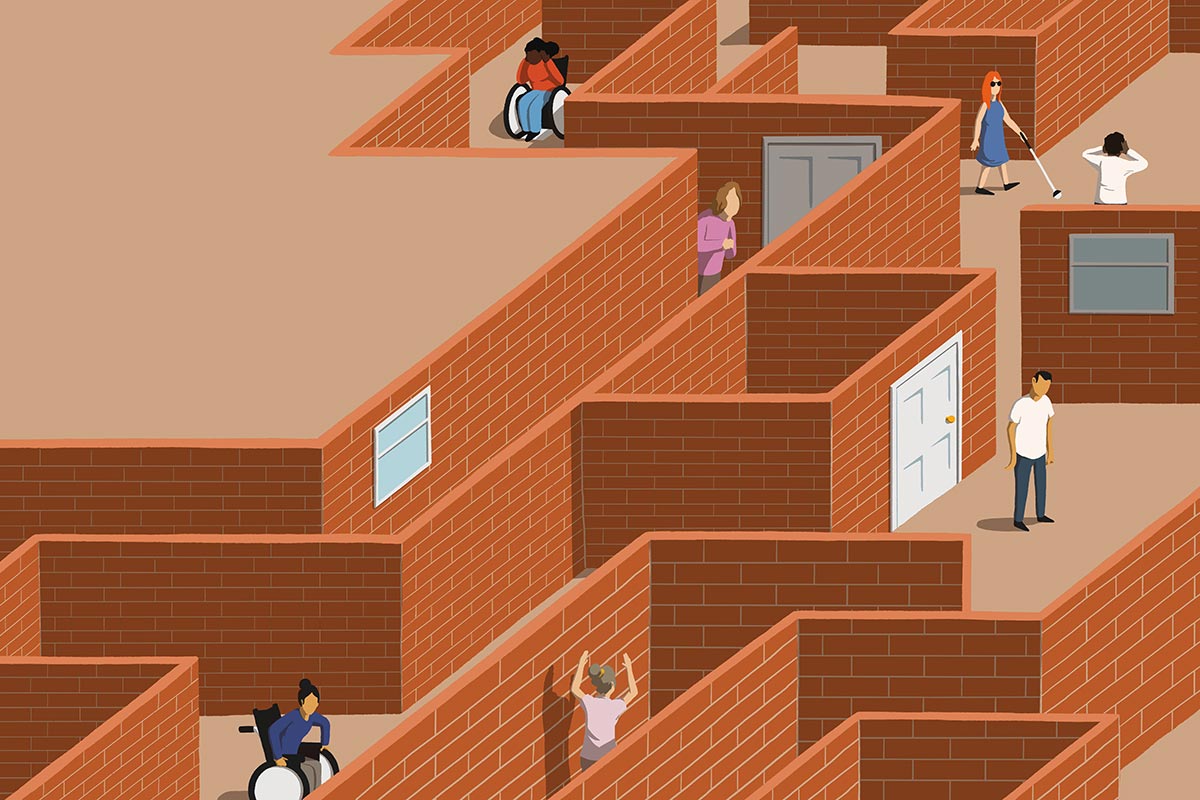

What the Down Syndrome Act means for housing

New legislation requires councils to take the needs of people with Down Syndrome more seriously. Cherry Casey reports. Photography by Oliver Edwards

For the first time anywhere in the world, England has passed legislation specifically to ensure the needs of people with Down Syndrome are met. The Down Syndrome Act became law in April, and places a duty on local authorities to “assess the likely social care needs of persons with Down Syndrome and plan provision accordingly”, says Conservative MP Dr Liam Fox, who presented the bill.

Guidance on how to meet these specific needs will be created by 2023, and will focus on the areas of education, health, social care and housing. Inside Housing wanted to find out what this means for the housing sector, and how it can provide the right support to tenants with Down Syndrome.

Sam Potterton, from Bristol, has Down Syndrome and has lived in a rented home with a friend for 11 years. “I enjoy living independently because I’m in control of my life,” he says. “I make my own decisions and I learn a lot of skills on the way.”

Domiciliary care agency New Key visits Mr Potterton three days a week to help with tasks such as shopping, arranging activities and paying the bills, but if he needs extra help outside of these hours, he can call them.

Gary Kent, one of the directors at New Key, says that Mr Potterton’s living arrangement is ideal for an individual with Down Syndrome.

He is offered tailored support, which enables him to live independently and – crucially – as part of the community. “This is really important,” Mr Kent says. If a vulnerable person is part of a local network, they have “a lot more protection than if they’re isolated with a support provider”.

Higher aspirations

Mr Potterton agrees that being part of his local community is important to him. “I enjoy bumping into people that I have got to know, such as in the local pub,” he says. “I feel safe here.”

Lynn Murray, founding member of the National Down Syndrome Policy Group (NDSPG), says that while in the past, “people with Down Syndrome were instantly put into an institution”, today the community is more readily included in the mainstream, which has resulted in better outcomes and longer life expectancy.

“But there is still scope for people with Down Syndrome to live longer and more healthily still,” she says, “and housing is one of the central tenets of that.”

Ms Murray’s own adult daughter, who has Down Syndrome, cannot wait to move out, she adds, and while it will be difficult to let her go, Ms Murray explains that not only is it a vital part of adulthood, but quite simply “the wise thing to do”, now that people with Down Syndrome are commonly outliving their parents.

Chris Watson, a social care commissioner at the Down’s Syndrome Association (DSA), recalls that when he was a social worker, there were occasions when a person with Down Syndrome was found “that we didn’t even know existed”.

“They’d been cared for in their entirety by their mum and dad, and after [their parents] died, it was an absolute nightmare for them,” he says.

A desire for independent living is already noticeable, with the DSA saying it is seeing “more and more people” with the condition looking to move out of their family home – in part, Mr Watson says, because they have higher aspirations than ever before. No longer do we expect people with Down Syndrome “to be pigeonholed… and sent to a day centre”, he says. “They’re expected to get employment, learn independent living skills and get their own home.”

Currently, the Down Syndrome Act is in the consultation stage, so it is not known what specific guidance will be given to local authorities, but Ms Murray says her hope is that with more consideration given to people with Down Syndrome, there will be more research into how better to serve this community’s needs.

There is a particular gap in specialist provision for people with Down Syndrome and dementia, meaning those with both conditions are often placed in a residential home for older people.

But this approach is not person-centred enough, Ms Murray says. For instance, “people with Down Syndrome tend to respond well to stimulation”, she says, “so [they need] models around them that can help to delay the symptoms of any sort of dementia”. At the moment, it is a case of “we have a person with Down Syndrome, we don’t know where to put them, but we’ve got to put them somewhere”, she adds.

Mr Watson agrees that people with Down Syndrome are often housed in accommodation that does not serve their needs. “People have been evicted because their support worker or residential home can’t cope with them, and sometimes that can end really badly with people being sectioned or sent to hospital units,” he says.

In other instances, people are placed far from their family and networks, or put in residential care, which is “quite paternalistic as a model and disempowering”. And for those yet to find any housing, living in the family home longer than they would like to “can put the whole dynamic of the family relationship under strain, which has a negative impact on an individual’s behaviours and mental well-being”, Mr Watson says.

Specific support

This is not to say there aren’t many innovative housing options out there. In fact, Mr Watson says, supported residential developments, where individuals have their own front door but can “pop out or pull a chord” when they need help, seem to be on a growth trajectory, while companies such as MySafeHome assist disabled people to find mortgages.

The problem, however, is that it is “fairly rare to come across that information being presented in a comprehensive way”, says Mr Watson. This means many people with Down Syndrome, and their families, have no idea what their options are or where to start.

Mr Watson believes local authorities should have housing brokers with an in-depth understanding of all the options available, plus a handle on how to communicate this information.

Any housing strategy for people with Down Syndrome must be hardwired with smart home technology, or tech-enabled care, he says, citing innovations such as sensors that ensure baths cannot overflow, or gas cookers cannot be left on as vital enablers of independent living.

Ms Murray adds that “communication is often difficult for people with Down Syndrome”, which can lead to them being “stuck in a situation where their mental health or physical health might deteriorate, and they just accept that, because they don’t know how to articulate otherwise”.

The NDSPG would like staff in various sectors, including housing, to undergo training to help with issues such as this, and supports the idea of people with Down Syndrome being employed by housing associations, “in order to develop empathy and understanding” of those with the condition.

Mr Kent emphasises the need for more joined-up working between the departments involved in a person’s care: the local authority housing department, the housing association and the support provider. “If it’s done separately, it won’t work,” he says, citing examples where a local authority has contested the housing benefit rate it has been asked to pay.

“The person in the middle, who has a learning disability, is the one suffering,” he says. Lets for Life, a charitable organisation that provides affordable housing for people with disabilities, does this brilliantly, Mr Kent says.

“New Key has worked with them for 20 years and there hasn’t been one disaster, and we’ve never had a local authority complain about rent levels.”

One criticism of the Down Syndrome Act is that there is no statutory duty for authorities to act on the guidance they are given, which Mr Watson says gives him cause for concern that it will have “no impact in some areas because the local authority is already stretched.” However, he adds, if it even brings “a bit of applied thinking to local authorities, then it has served some purpose”.

Ms Murray is more optimistic that authorities will consider more specialised strategies, explaining that in the first instance, there needs to be a much firmer grip on data. “How do you accommodate [a community’s] needs when you don’t know where they live?” she says.

Fundamentally, she hopes the act will lead to “greater recognition that people with Down Syndrome don’t belong in margins”, where they have been relegated “for far too long”.

UPDATE 13.12.2022

This article originally stated that Chris Watson's job title was social care advisor. This was in error, and has been correctly to social care commissioner.

Sign up for our care and support newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters