You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The women who reinvented housing

Why did suffrage campaigners set up a housing association? Jess McCabe finds out. Pictures by Alamy and Women’s Pioneer Housing

Clockwise from top left: 34 Kensington Park Gardens; benefactor Ray Strachey; Maud Joachim (far left) who invested in Women’s Pioneer

The offices of Women’s Pioneer Housing are an unlikely location to discover a treasure trove.

But tucked on the edge of north London’s zooming A40, in a modest, warren-like office, inside a big safe, that is exactly what this 990-home housing association has found.

Chief executive Denise Fowler hovers at the edge of the safe as Inside Housing is allowed a quick look from a distance at bundles of documents and letters.

We can’t pore over the papers ourselves because “they are too precious”, explains Lisa Thompson, the association’s press officer, who has been carrying out cursory examinations of the remarkable find.

“And a bit fragile,” adds Ms Fowler. “I’ll be much happier when it’s all been archived digitally.”

Within the next year, thanks to a Heritage Lottery Fund grant, the contents will be brought out of the safe and made available online, so everyone can see them.

What we are talking about is an important, and hitherto almost unknown, slice of history: the papers show how a phenomenal group of suffrage campaigners came together in 1920 to found Women’s Pioneer, why they did it, and the impact it had on the first tenants – working and professional women.

"Lisa Thompson has gone through some of the documents and already revealed some amazing gems"

For the first time, it uncovers the depth of links between the feminist movement to gain the vote and early social housing campaigners.

It all started because the organisation was looking at how to celebrate the 100th anniversary of its founding. “I’d been told of the suffrage connection but I had no tangible evidence of it, just a few signatures,” recalls Ms Thompson. “But then you start digging and talking to suffrage historians, and...” (she makes a ticking noise, to show how everything fell into place).

So what has Women’s Pioneer uncovered about its founding mothers (see box: Founding members)? And what are the next steps?

Women’s Pioneer still doesn’t know exactly what it has on its hands, because the project to investigate the papers fully hasn’t started.

But Ms Thompson has carefully gone through some of these documents and already revealed some amazing gems. That includes the minutes of the organisation, dating back to its founding on 4 October 1920, through the war years. There is also an enticing bundle of letters.

What they know so far is interesting enough. Women’s Pioneer was founded in the aftermath of World War I and the Representation of the People Act 1918 – which gave women aged over 30 who owned property the vote.

The idea for Women’s Pioneer came from Etheldred Browning. After working on women’s welfare issues in Dublin, she came to London and started to do the same here.

“There was a massive homelessness problem in the UK after the war, but so far all the attention had been focused on the men, these returning heroes, and women were just being brushed aside,” explains Ms Thompson.

Listen to a sound recording from the interview with Denise Fowler:

There were 1.5 million more women than men, after the slaughter of the Great War.

Meanwhile, despite the push to put women back in the home after the war, many women stayed in the workforce and were also entering professions for the first time.

Ms Browning gathered evidence that landlords did not want to rent to women – preferring more lucrative couples, or to rent to men, who were paid more. She started to agitate for a new housing association for women.

“Women themselves couldn’t get mortgages in their own name at that point, so setting up a company enabled them to do that,” Ms Fowler explains.

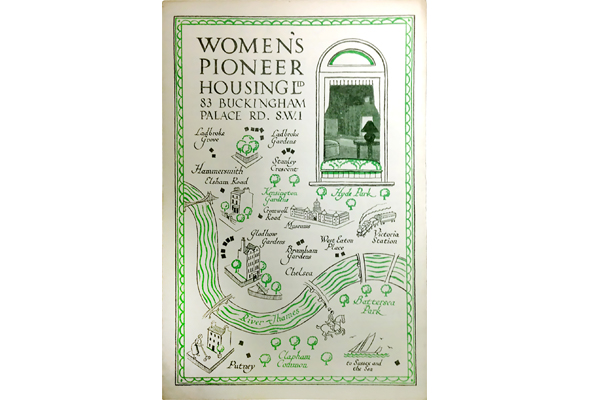

An original brochure

The founding members bought shares in the company, which raised the money to buy Women’s Pioneer’s first homes.

Those founders were some of the most interesting women of their day. They included both suffragettes (whose “deeds not words” approach used militant, lawbreaking resistance to get the vote), and suffragists (who pursued non-confrontational methods). Although generally seen as opposing each other’s tactics, and basically not getting along well, the documents show that was not the case.

One of the founders was Helen Archdale, an ‘inner circle’ suffragette who went to prison for window breaking.

Money to purchase the first Women’s Pioneer property on Holland Park Avenue was raised by Ray Strachey, one of the most famous of the peaceful suffragists, who wrote a famous account of the effort to gain the vote, called The Cause.

That property was bought with £2,500 from an anonymous donor and £500 from Lady Rhondda, the daughter of a viscount whose militant actions included jumping on the car of prime minister HH Asquith and trying to blow up a postbox. She spent time in prison and on hunger strike.

Founding members

Etheldred Browning (the founder), an Irish suffragist who ran the women’s section of the Garden Cities & Town Planning Association.

Lily Carre, an Irish suffragist and social worker.

Miriam Homersham, an auditor and one of the first women to start her own accountancy practice.

Agnes Miall, journalist, author of The Bachelor Girl’s Guide to Everything, 1916 (published when she was 24), and one of the BBC’s first female broadcasters.

Annabel Dott, variously described as an architect (self-taught) but more credibly in one contemporary news story, as the UK’s “first woman builder”.

Mabel Bruce, a friend of Ms Browning from Ireland, living on private means.

Source: Women’s Pioneer

“Women’s suffrage tended to be seen in isolation, but actually it was part of a network of different activities women were carrying out to advance women’s position in relation to their general welfare, including their housing and their ability to work,” explains Ms Fowler.

By 1920, other housing projects for working women did exist. But they were often run on paternalistic lines and aimed to safeguard the residents’ “respectability”.

The Ada Lewis Trust hostel, near Elephant and Castle, was made up of bedroom cubicles, with gaps under the doors to monitor the visitors. “It was like a toilet cubicle – horrible,” exclaims Ms Thompson. By Victoria railway station, there was the Girls’ Friendly Society Hostel. Now owned by the homeless charity St Mungo’s, a stained glass window instructed the original lower and middle-class working women who lived here to “keep innocency”.

The Women's Pioneer logo

Women’s Pioneer’s facilities were often communal too, partly to keep costs down. Some early buildings included restaurants.

“There are family members who remember what it was like then, and through them we’ve got some great stories about women coming in from work and kicking off their heels and dancing together in the communal corridors,” Ms Thompson laughs. But crucially women had their own private bed-sitting rooms.

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph reported when the first Women’s Pioneer building was opened on Holland Park Avenue: “The six flats are all let to professional women who will be able to have their own treasures about them, invite their own friends when they wish, indulge in solitude at times and enjoy the privileges that hitherto have been impossible for women workers.”

Early tenants

May Havers, a tenant board member and suffragette, lived in Gliddon Road from 1933 until her death. “She was always tying herself to railings and being arrested. Edith, her grandmother, would have to rush in and get everything sorted out,” Ms Thompson says.

The logo of Women’s Pioneer – still the same nearly 100 years later – shows a woman reclining on a chair, her feet up, reading a book. A vase of flowers in the window hints at domestic peace. This new association gave residents the potential for a comfortable and private life. By implication, there was also the potential for a sex life.

The archives will probably produce new insights on lesbian history as well. “It was pretty clear there were women who were involved in relationships with each other. And this was a place where women could feel safe about that,” says Ms Fowler.

At first the tenants were professional women who could afford to buy shares, but quickly this expanded as working women were nominated for flats. “There were so many women who were trying to make a go of it in their jobs, and then they were just delighted that they’d found somewhere secure to live,” she adds.

The next steps in the research should uncover even more detail. With £79,000 in funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and £14,000 added from Women’s Pioneer, a project co-ordinator has just been appointed and Ms Thompson is taking on a researcher role. They will soon dig into those papers in earnest to find out what they can tell us about women’s history and housing history.

Volunteers will also research the early years of the organisation and its first tenants.

Four properties Women’s Pioneer owned in Holland Park Avenue, including number 167. This (then number 67) was its first property, bought for £3,000

The papers will be digitised and prepared for a travelling exhibition. A film and website will make what was once hidden history readily available. A pack for teachers will be produced for use in schools.

Alongside this, Women’s Pioneer is working with the Chartered Institute of Housing and the National Housing Federation on research into women’s housing issues today – which are both different from, and similar to what inspired those suffrage campaigners to set up the association back in 1920.

“The majority of women in London [today] are going to have difficulty finding and retaining affordable accommodation, and being able to then continue working as nurses, doctors, teachers and social workers,” says Ms Fowler.

“One of the fundamental rights is to have a place where you can close the door, be safe and secure, and have control of your life. So many women at that time, and still now, don’t have that comfort" Denise Fowler

“A lot of our early tenants were nurses, because they’d gained their experiences during World War I and were continuing to nurse but couldn’t find suitable housing.

“One of the fundamental rights is to have a place where you can close the door, be safe and secure, and have control of your life. So many women at that time, and still now, don’t have that comfort,” she adds.

Excitingly, Women’s Pioneer hopes that some of its tenants will volunteer to research the original inhabitants of their own flats. “We have lots of really skilled, capable women among our tenants,” Ms Fowler says.

As the research begins, Inside Housing will be following the story and providing updates. Many precious stories are likely to emerge from those bundles of fragile papers in the corner of the safe.

Soon, Women’s Pioneer will start to bring those tales of the founders and first tenants to light. It’s a responsibility the association takes seriously. As Ms Thompson concludes: “We started to talk about ‘my women’. You start to think ‘these are my people’; you feel responsible for their welfare.”

Inclusive Futures

Inside Housing’s Inclusive Futures campaign aims to promote and celebrate diversity and inclusion.

We are pledging to publish diversity audits of our own coverage.

We are also committed to proactively promoting positive role models.

We will do this through the pages of Inside Housing. But we will also seek to support other publications and events organisations to be more inclusive.

Our Inclusive Futures Bureau will provide a database of speakers and commentators from all backgrounds, for use by all media organisations.

We are also challenging readers to take five clear steps to promote diversity, informed by the Chartered Institute of Housing’s diversity commission and the Leadership 2025 project.

INSIDE HOUSING’S PLEDGES

We will take proactive steps to promote positive role models from under-represented groups and provide information to support change.

We pledge to:

Publish diversity audits: We will audit the diversity of the commentators we feature. We will formalise this process and publish the results for future audits twice a year.

Promote role models: We will work to highlight leading lights from specific under-represented groups, starting in early 2018 with our new BME Leaders List.

Launch Inclusive Futures Bureau: We will work with the sector to compile a database of speakers, commentators and experts from under-represented groups. The bureau will be available to events organisers, media outlets and publications to support them to better represent the talent in the sector.

Take forward the Women in Housing Awards: Inside Housing has taken on these successful awards and will work to grow and develop them.

Convene Inclusive Futures Summit: Our new high-level event will support organisations to develop and implement strategies to become more diverse and inclusive.

THE INCLUSIVE FUTURES CHALLENGE

Inside Housing calls on organisations to sign up to an inclusive future by taking five steps:

Prioritise diversity and inclusion at the top: commitment and persistence from chief executives, directors and chairs in setting goals and monitoring progress.

Collect data on the diversity of your board, leadership and total workforce and publish annually with your annual report. Consider gender, ethnicity, disability, sexuality, age, and representation of tenants on the board.

Set aspirational targets for recruitment to the executive team, board and committees from under-represented groups.

Challenge recruiting staff and agencies to ensure that all shortlists include candidates from under-represented groups.

Make diversity and inclusion a core theme in your talent management strategy to ensure you support people from under-represented groups to progress their careers.