The unexpected power of a postal address

An app that connects homeless people with donated postal addresses sounds like it would be simple and helpful for people to set up benefits and do other life admin. It was more of a success than anyone could have expected. Hannah Fearn reports

Homeless people with no fixed address struggle to apply for bank accounts or housing benefits. But an app piloted in Lewisham is changing that by donating addresses so that homeless people can get off the streets and rebuild their lives.

Owen Phillips had been renting rooms and sofa-surfing around Lewisham for decades before he finally became homeless in 2020. With rents rising and the pandemic putting pressure on housing, he suddenly found himself with nowhere to go.

“I was trying to find something myself. I was renting rooms, finding somewhere on my own, but the state they were in was awful and they were asking for £1,000 a month,” he told Inside Housing. At the age of 67, Mr Phillips had no place to call home.

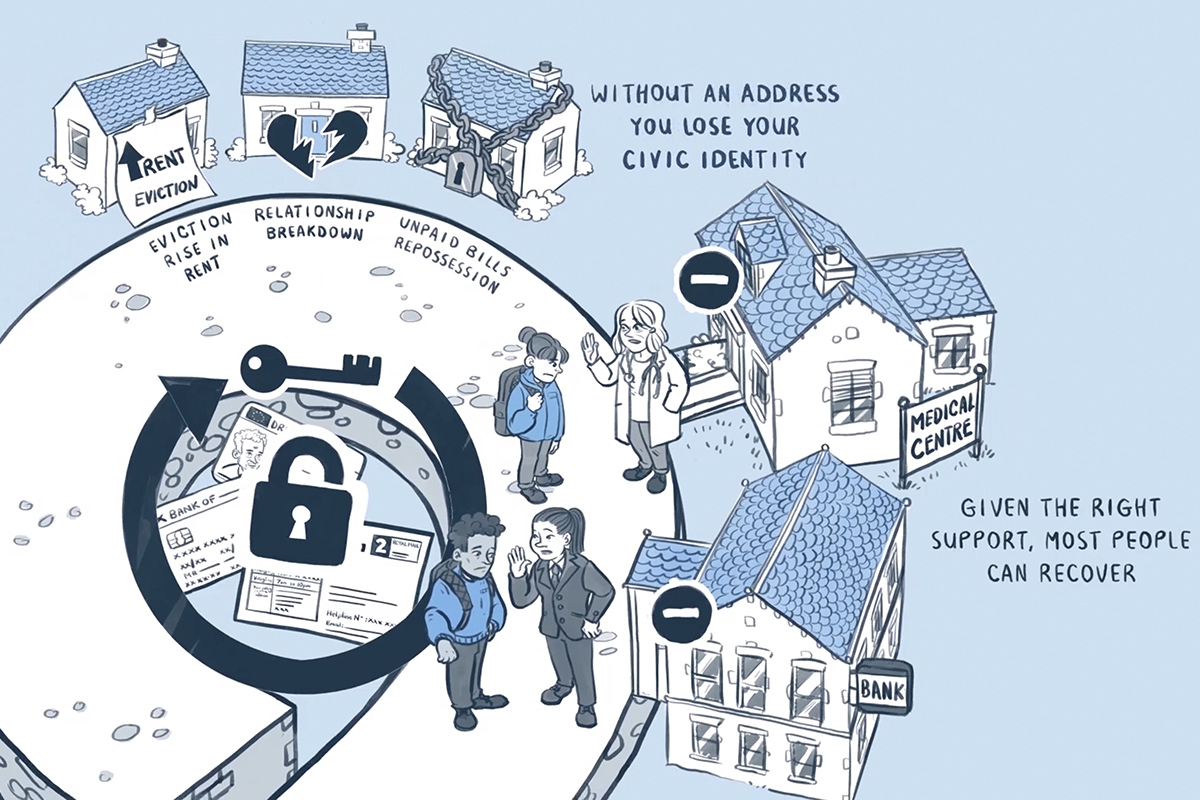

He was on the housing register and was getting support from the local authority, but was trapped in a vicious cycle. With no address, he couldn’t set up a bank account. With no bank account, he couldn’t claim housing benefit. It is an administrative crisis that perpetuates homelessness and can lead to people falling out of the system. The turning point came when Lewisham Council invited Mr Phillips to sign up to ProxyAddress, a pilot scheme where homeless people can use an app to get a temporary address to manage their admin.

“They made up an address for me and took it from there,” explains Mr Phillips. “I was able to get a bank account sorted out, and the rest is history.”

Within a few weeks he was allocated a stable home through Merchant Taylors’ and Christopher Boone’s Almshouses Charity.

“They got in touch, I came for an interview, they showed me the flat and I got it,” he says. Within six months of becoming homeless, Mr Phillips now had a stable tenancy, and was receiving housing benefit and pension credit.

His story is not a one-off. Lewisham has seen repeat success in getting people out of homelessness and into secure tenancies with the help of this innovative app.

Of the 49 homeless people who took part in the ProxyAddress pilot between 2020 and 2021, 47 moved into stable accommodation within six months. Many of the tenants also moved back into employment, all because they were provided with an address.

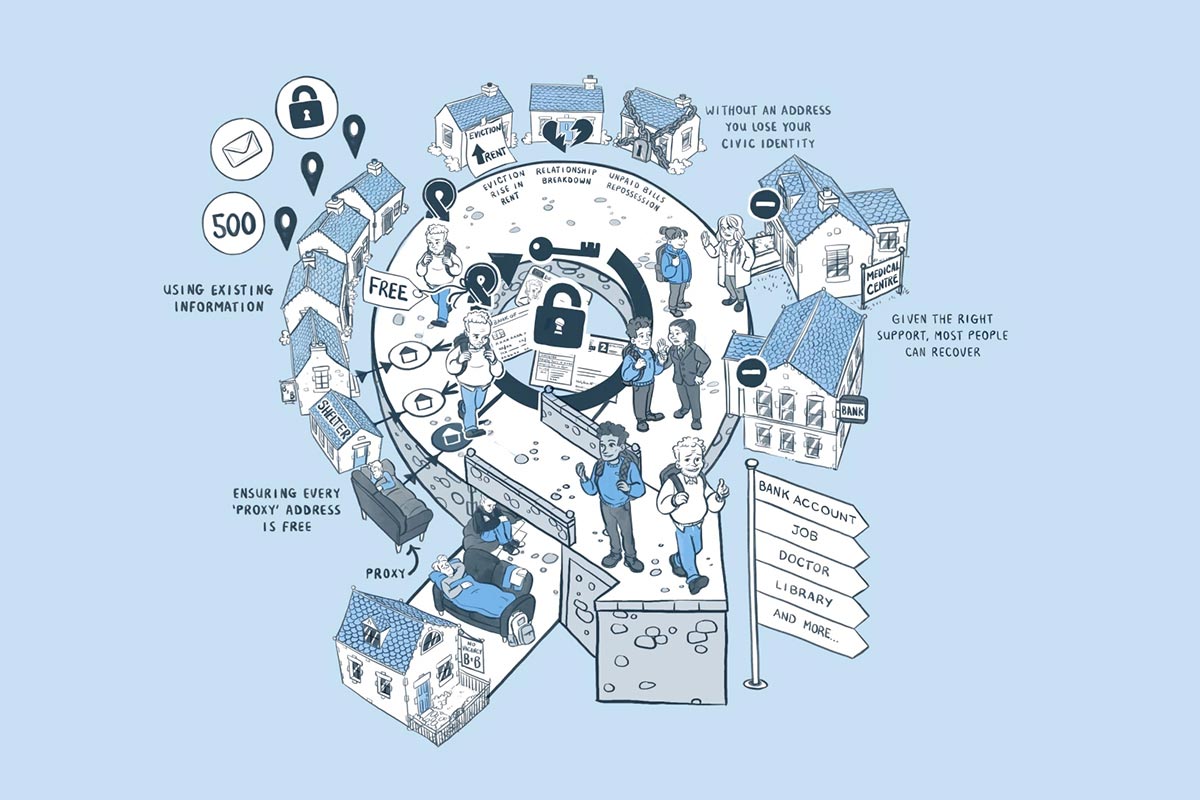

The scheme is the brainchild of architect Chris Hildrey. With an interest in how design techniques can be used to address social issues, Mr Hildrey realised that much of the way society speaks about homelessness bears little relationship to how it is experienced and that what all homeless people lack is an address.

Mr Hildrey wanted to find a practical way to use design and technology to solve this administrative crisis. He posed the question: how can we use technology to give homeless people an address so they can access the public services that those of us with a home take for granted? The answer was the ProxyAddress app.

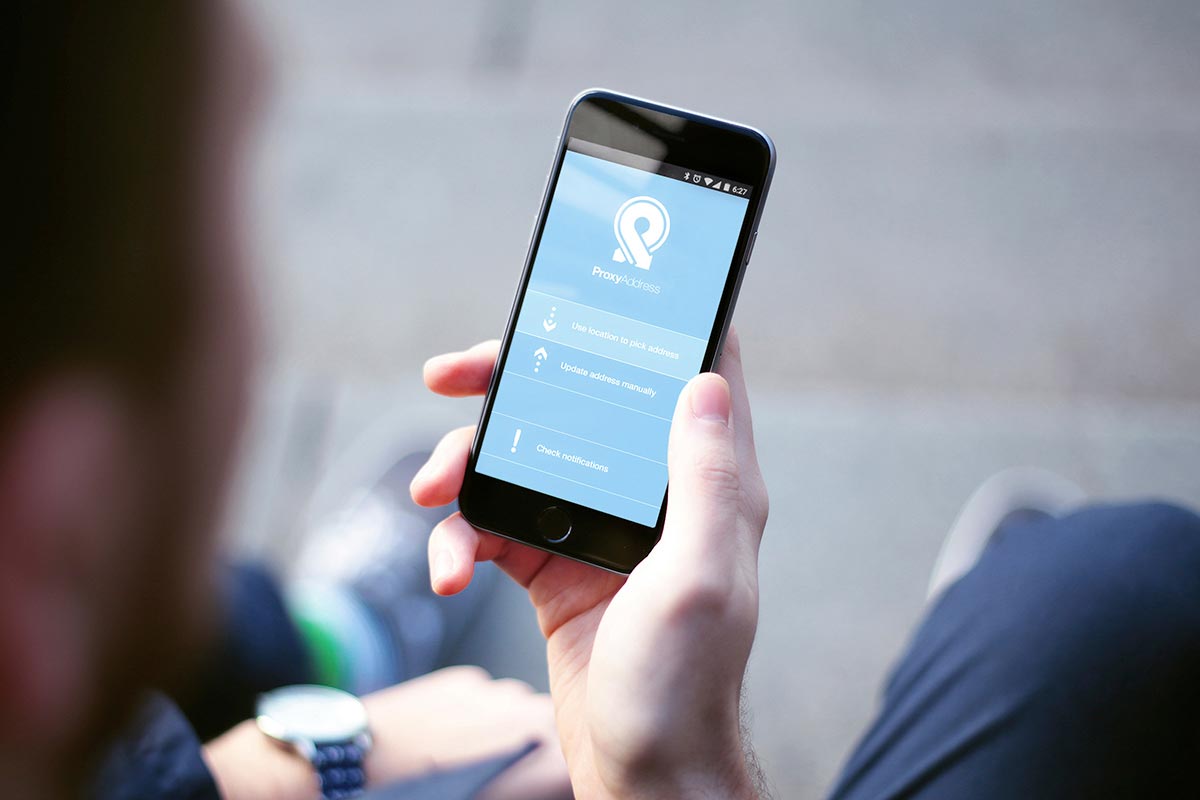

During an internship at the Design Museum in London six years ago, Mr Hildrey hit on the idea of using code to design an app that duplicates the address of a property, so that any homeless person can have an address to use for everything from opening a bank account to applying for a job, signing up for a library card, and even registering on the housing waiting list.

The way the app works is simple. Willing property owners donate an address, including councils and housing associations which provide addresses of empty properties or those still under construction. Applicants are then matched with an address, which becomes theirs for the purpose of admin. Royal Mail has partnered with the scheme to ensure all hard copy mail reaches the service user wherever they are staying, and the app that manages the address ID can be updated in real time.

“We expected optimistically that 25-35% of service users in a six-month period would recover from homelessness,” Mr Hildrey explains. The results of the pilot, however, exceeded expectations. Almost everyone who took part moved into a stable tenancy. “It was a catalyst for people,” Mr Hildrey adds.

From idea to reality

Creating the app took time. Mr Hildrey faced challenges in protecting the coding from the risk of identity theft and data fraud. Once the creases were ironed out, in 2020 he began working with Lewisham to pilot the scheme, bringing local service providers on board, including banks, libraries and GP surgeries. With stakeholders signed up, by 2021 the pilot was ready to launch.

There were some stumbling blocks. Louis Colley, rough sleeping co-ordinator at Lewisham Council, was involved from the early stages. He had initially hoped that housing officers across the local authority could be trained up to use the tool, with the intention of supporting people when they were still only at risk of homelessness, rather than after they had lost a home. When that proved too complicated, his team instead took referrals, dealing with all applicants through the rough sleeping team.

“Because the majority of the referrals were coming from the rough sleeping cohort, it made sense that we completely led on the project,” Mr Colley says. The results were remarkable, with the app making a huge difference during the pandemic. Complex cases of long-term rough sleepers who had no formal identification, and who were often difficult to reach and engage with, especially benefited. With an address provided by the app, homeless people and council support staff soon found that long, complex administrative processes were sped up. Whereas helping a homeless person get a bank account used to take months, the app meant it could be done in a day – even without formal ID and with only a referral letter from the council to recommend them.

“A bank account allows us to apply for benefits, and makes it easier to apply for ID, so we’re getting these things in place to set them up and make them ready for an emergency accommodation placement,” Mr Colley explains. “We were able to get tangible work done almost instantly. It just made the process of resettlement a lot quicker.”

A faster system meant that homeless clients stuck with their case workers. Previously they risked drifting out of the system, disillusioned by long waits.

While the app had been met with optimism, no one expected it to achieve so much so quickly.

One client, who did not wish to be interviewed directly for this piece, moved on from homelessness to secure housing within six months, while gaining full-time employment and a promotion in the same period. With a safe place to call home and a stable income, he arrived to meet Mr Hildrey to talk about the success of the project in his own car.

Mr Colley admits that the pressure to bring “everyone in” during the early spread of COVID-19 helped focus the council’s minds on the use of ProxyAddress. But he also believes the project’s impressive results can be replicated, despite the wrapping-up of the ‘Everyone In’ initiative to get rough sleepers off the streets during the pandemic.

The ProxyAddress pilot has been watched closely by Tom Copley, London’s deputy mayor for housing, who hopes to see it expand to other local authorities in the capital. He is working with councils to help them understand its potential.

He was taken aback by the impact that a scheme addressing such a “long-standing and well understood issue” had. “I wasn’t surprised it was making a real difference, but I was pleasantly surprised by how overwhelming it was,” he says.

Lewisham Council’s Mr Colley is now working with local colleagues across the capital’s south-east boroughs to spread the use of ProxyAddress locally. Meanwhile, a further eight cities across the UK are set to trial the technology.

One of the first to take it up will be Glasgow, with other metropolitan councils expected to confirm their involvement later this year. Mr Hildrey is also seeking funding for further roll-outs, and within two years of use the projects should become self-funded.

While local authorities will have to pay to sign up to use the service, the savings they make in terms of the cost of resolving homelessness should be more than offset, including savings on temporary accommodation and anti-social behaviour enforcement.

Each local authority negotiates the cost depending on their specific needs, the size of the authority and other variables. Lewisham Council had a discount for being the first mover. The average cost for a local authority is £20,000-£30,000.

As well as rolling out across the UK, councils are hopeful that ProxyAddress will develop to become available to people at risk of losing a home or tenancy, preventing the slide into homelessness.

“I think we’ve only just touched the surface of what we could do here,” Mr Colley says. “The potential it has is amazing.”

Lewisham Council has continued with ProxyAddress following the end of the pilot, and it is now being taken up by other local authorities.

As for Owen Phillips, after decades of housing insecurity, he’s finally able to relax into his retirement. “It’s good,” he says. “That’s always what I wanted.”

Sign up to our Best of In-Depth newsletter

We have recently relaunched our weekly Long Read newsletter as Best of In-Depth. The idea is to bring you a shorter selection of the very best analysis and comment we are publishing each week.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.