One man’s battle to improve tower block safety

Architect Sam Webb has campaigned to improve safety in tower blocks since four people died in Ronan Point 50 years ago. He warned of fire spreading in high rises long before Grenfell. Martin Hilditch asks him what needs to be done to avoid future tragedies. Photography by John Robertson and Alamy

Throughout this week we are publishing a number of articles on building safety to mark the 50th anniversary of the Ronan Point disaster

Sam Webb has been warning about fire and structural dangers in tower blocks for most of his working life. Tragically, he keeps being proved right.

We’re interviewing Mr Webb in his Cambridgeshire home because it is 50 years since the collapse of the Ronan Point tower block in Newham, London, in which four people died. Before the disaster Mr Webb, an architect, was already investigating safety concerns with large panel system (LPS) buildings such as Ronan Point (built out of prefabricated panels, with some of the walls on each floor supporting those directly above).

A thorn in the side of various governments ever since, he has continually pushed for more action to address safety issues. He was instrumental in getting Ronan Point demolished in the 1980s, after it was initially reoccupied.

This is the story of a career dedicated to keeping tower block residents safe. But it is also about years of failure from central government to take responsibility for tower block safety and implement solutions.

Half a century after Ronan Point, as we look to make sure a disaster like Grenfell Tower never happens again, it is sadly more relevant than ever.

A born storyteller, Mr Webb talks enthusiastically, often punctuating his points with a disbelieving laugh at the various examples of bad practice he has uncovered over the years.

He first became concerned about LPS blocks shortly after he qualified as an architect in 1962.

This was an era of mass construction, as the country rebuilt after World War II, and successive governments saw prefabricated tower blocks as a way of delivering hundreds of thousands of low-cost homes.

In 1964, Mr Webb’s first wife was a fourth-year student at the Architectural Association School of Architecture and her year visited an LPS site in Greenwich.

They arrived as a load-bearing wall was being lowered onto bolts designed to help hold it in place.

“They lower it down and it won’t fit on the bolts. So these men come out with these big steel chisels and hammers, and start chipping away. They lift it up, lower it down. It still won’t fit. So the foreman beckons to this man, who comes out with a sledgehammer, and he bangs the bolt flat.

“Quick as a flash one student says, ‘Excuse me, should you really be doing that?’ And they are all whisked off the site, put on the bus and sent back,” Mr Webb states, adding that “the penny dropped with us” about the risks posed by the buildings.

Together with his future business partner George Fairweather, Mr Webb began to question the safety of this form of construction. “We started collecting stuff on these systems,” he says. “We did talk to people about it; engineers and so on. Some engineers were a bit quizzical.

"Others embraced it. It was huge money for them. And everybody assumed that as the government was backing it, it had to be alright.”

But, as Mr Webb and a few others feared, it wasn’t alright. On 16 May 1968 there was a gas explosion in Flat 90, on the 18th floor of Ronan Point.

This blew out the load-bearing wall of the living room and bedroom, starting a progressive collapse in which four people were crushed to death.

By this time Mr Webb was working as an architect at Camden Council. “People were just stunned,” he says of the atmosphere that day.

"The Ronan Point inquiry also pointed out that system-built blocks might be liable to progressive collapse as a result of fire"

The subsequent inquiry later in 1968 resulted in a number of recommendations and circulars being issued by the government.

Broadly speaking, these meant that existing buildings with gas systems should be assessed to see if they could withstand static pressure of 5lb per square inch (psi) – and this was the minimum standard new buildings must meet. With widespread failures, councils were told that existing buildings where the risk of explosion could be reduced by removing gas supplies now had to meet 2.5 psi (if they didn’t already).

The inquiry also pointed out that system-built blocks might be liable to progressive collapse as a result of fire, although this was only briefly touched on and attention afterwards chiefly focused on gas. No one ever made sure councils appraised their blocks, however. Years later in 1984, the then-housing minister Ian Gow admitted “the ministry did not ask authorities to inform it of the appraisals or specific action taken”.

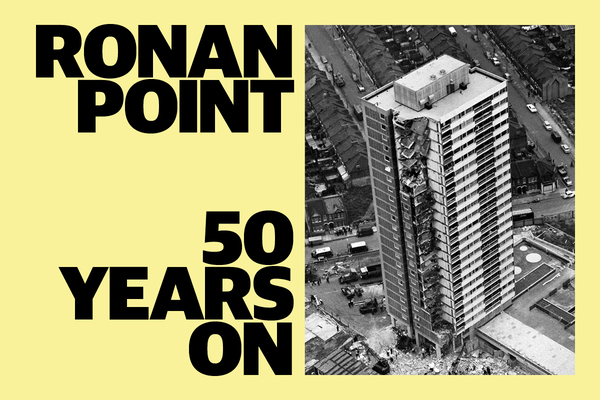

Aerial view of the collapsed flats in Newham, London

A busy period followed for Mr Webb, working with Paul Foot, a journalist at Private Eye magazine, to investigate Ronan Point and wider tower block safety failings.

This led to the uncovering of a notorious corruption scandal involving architect John Poulson that resulted in the resignation of home secretary Reginald Maudling in the 1970s.

It was in the 1980s though, when Mr Webb – by then lecturing at the Kent Institute of Art and Design – really made his name.

The National Tower Blocks Conference in 1983, where he spoke, was a turning point. Ronan Point tenants were there, along with Fred Jones, who chaired Newham Council’s housing committee. Ronan Point had been reoccupied, with the collapsed corner rebuilt. Tenants told Mr Webb about large gaps between the walls and floors in the block, and Mr Jones invited him to conduct a survey of it.

During the survey, Mr Webb tore off a strip of paper and dropped it through a gap in a tenant’s wall. It disappeared completely, indicating substantial gaps in the structure.

“One of the tenants said: ‘What have you done?’” Mr Webb says. “And I said: ‘I have just killed Ronan Point.’”

Mr Webb tore off a strip of paper and dropped it through a gap in a tenant’s wall. It disappeared completely, indicating substantial gaps in the structure.

He was right. By 1984, based on surveys carried out by Mr Webb and his students, the council had evacuated the block. Mr Webb insisted the block was dismantled rather than knocked down, to evidence exactly what had gone wrong. Just as importantly, he wanted to conduct a fire test on the empty building, feeling that there had been little focus on the potential impact of fire on large panel structures. He got his way – despite much official opposition – and a fire was lit in one of the empty flats. The test was meant to last 20 minutes.

“I stood on my own in front of the building thinking, ‘S**t, if I’ve got this wrong, they are going to nail me to the outside’,” Mr Webb laughs. “But I knew I was right.”

After 10 minutes, the dark smoke coming out of the flat “suddenly turned to white smoke, like a new pope had been elected”, indicating the fire had been put out early.

Mr Webb walked over to the building and was “met by these panic-stricken engineers from Newham and the Building Research Establishment who [were] all running out of the building”. When Mr Webb tried to enter he says he was told, “You can’t do that, the building’s going to fall down.”

The then-housing minister Mr Gow later admitted that safety limits on how much load-bearing ceiling panels could safely move because of the heat were reached after 10 minutes of the fire starting. He told MPs in 1984 that “the test was stopped although the severity of the fire was beginning to decline and it is unlikely that further structural deformation would have occurred”. Mr Webb, however, says he knows what he saw on the day, and the movement recorded was potentially “very dangerous”.

In any event, councils were asked to appraise all their Taylor Woodrow Anglian buildings “to establish whether joints between panels can resist the spread of fire and fumes accurately”, and whether the joints provided adequate margins of safety.

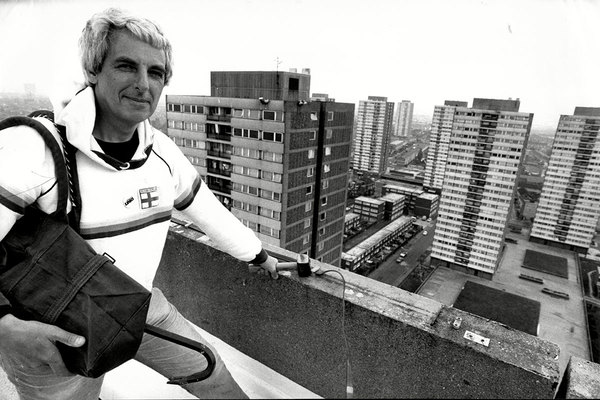

Sam Webb on the roof of Ronan Point after exploring defects in the structure, 1 May 1984

Readers can probably guess by now what happened next – in fact, they will have to, because yet again the government didn’t track what, if anything, councils did. The article I wrote after meeting Mr Webb for the first time in 2005 was headlined ‘Lack of central checks leave flats in danger of collapse’. It came as Southwark Council removed the gas supply to some blocks on its Aylesbury Estate. Similar issues had been discovered on the Packington Estate in Islington in 2004. Then-housing minister Keith Hill admitted there was a “possibility” some LPS blocks had not been checked for robustness in accordance with either the 1968 regulations or 1987 guidance from the Building Research Establishment.

Inside Housing has carried out additional research into the current state of play with LPS blocks – and a number of problems have been discovered in the past year.

“I remember us all discussing Lakanal and saying, ‘If they don’t change the regulations and this happens at night, the death toll will be massive'" Sam Webb

As Mr Webb suggests, it’s depressingly like Groundhog Day. “After Ronan Point was knocked down, the general official attitude was ‘game over – mission accomplished’,” Mr Webb states. “But it wasn’t.”

Possibly the toughest point of Mr Webb’s career came, however, when he acted as an expert witness for the families who lost loved ones in the 2009 Lakanal House fire. This involved a trip around the tower block, looking at the evidence in 2011. It still haunts him.

“Nothing in your education can prepare you to go into a room, a tiny room – 2 by 2.5 metres with a bath, a toilet and a sink. Nothing can prepare you to go into that room and see the imprints of all these tiny feet and other feet and realise five people died in there.”

Sadly, the coroner’s recommendations following Lakanal House, such as updating building regulations and installing sprinklers in blocks, went virtually ignored until Grenfell.

“I remember us all discussing Lakanal and saying, ‘If they don’t change [regulations] and this happens at night, the death toll will be massive’,” Mr Webb says. “And they didn’t.”

Mr Webb is clear in his mind that there are serious central contributing factors to the Grenfell Tower tragedy, in which 72 people lost their lives.

“The political philosophy which drives all of this is the political philosophy that sees regulations as being a burden on industry,” he states. “That is where you get [former prime minister David] Cameron’s war on red tape. What does he think those laws are for? They are to protect people.”

Clippings from Inside Housing and Housing Today

Mr Webb has again been heavily involved in calling for change following Grenfell. At the end of April this year he was one of the signatories to a letter to the government stating that “10 months on, we are deeply concerned that so little has been done to prevent another fire”.

It called on the government to urgently implement changes, including making sure that only non-combustible cladding and insulation be installed on high-rise buildings. Other signatories included the chair of the Royal Institute of British Architects’ expert advisory group on fire safety.

Fifty years after Ronan Point, Mr Webb says his 30-year-old self “would be horrified” at how little has changed.

Despite, or perhaps because of, this Mr Webb shows no sign of backing away from the fight. He thinks that’s exactly what successive governments have done, though.

“This is a national problem and it cannot be solved by local authorities,” he states about the current state of play for LPS blocks. “It can only be solved by government stepping in with money.”

Ronan Point: 50 years on

We have published a series of articles to mark the 50th anniversary of Ronan Point:

Are tenants being listened to on building safety? Tower block safety campaigner Frances Clarke questions whether Dame Judith Hackitt is really listening to tenants

The tower blocks that time forgot Fifty years ago councils were told to assess high-rise buildings that were similar to Ronan Point and strengthen them where necessary. So why are problems with some of the blocks still emerging?

One man’s 50-year battle to improve tower block safety Meet architect Sam Webb, who has been campaigning on safety in tower blocks since the disaster at Ronan Point

The worrying legacy of a disaster Jules Birch reflects on what we can learn from the Ronan Point disaster

Watch a new film about Ronan Point Filmmaker Ricky Chambers, whose grandparents and mother lived in Ronan Point, has made a film telling people’s stories of the ill-fated block. Watch the film and read Mr Chambers’ comments on why he made it

The dangers of large panel system construction Building safety expert Sam Webb explains why the system of construction used at Ronan Point was flawed, and how it was used in other buildings still occupied today

The Paper Trail: The Failure of Building Regulations

Read our in-depth investigation into how building regulations have changed over time and how this may have contributed to the Grenfell Tower fire:

The Hackitt Review

Photo: Tom Pilston/Eyevine

Dame Judith Hackitt’s (above) interim report on building safety, released in December 2017, was scathing about some of the industry’s practices.

Although the full report is not due to be published until later this year, the former Health and Safety Executive chair has already highlighted a culture of cost-cutting and is likely to call for a radical overhaul of current regulations in an interim report.

Dame Hackitt’s key recommendations and conclusions include:

- A call for the simplification of building regulations and guidelines to prevent misapplication

- Clarification of roles and responsibilities in the construction industry

- Giving those who commission, design and construct buildings primary responsibility that they are fit for purpose

- Greater scope for residents to raise concerns

- A formal accreditation system for anyone involved in fire prevention on high-rise blocks

- A stronger enforcement regime backed up with powerful sanctions

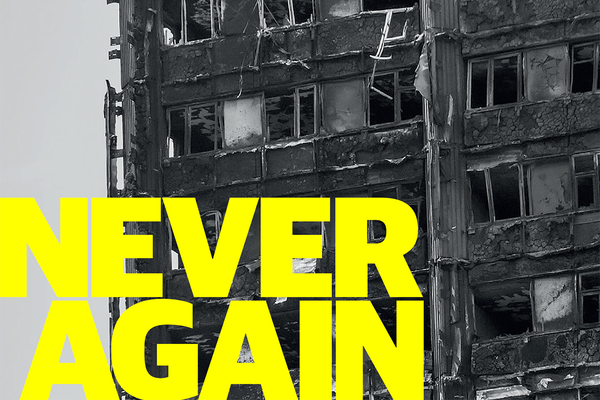

Never Again campaign

In the days following the Grenfell Tower fire on 14 June 2017, Inside Housing launched the Never Again campaign to call for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

One year on, we have extended the campaign asks in the light of information that has emerged since.

Here are our updated asks:

GOVERNMENT

- Act on the recommendations from Dame Judith Hackitt’s review of building regulations to tower blocks of 18m and higher. Commit to producing a timetable for implementation by autumn 2018, setting out how recommendations that don’t require legislative change can be taken forward without delay

- Follow through on commitments to fully ban combustible materials on high-rise buildings

- Unequivocally ban desktop studies

- Review recommendations and advice given to ministers after the Lakanal House fire and implement necessary changes

- Publish details of all tower blocks with dangerous cladding, insulation and/or external panels and commit to a timeline for remedial works. Provide necessary guidance to landlords to ensure that removal work can begin on all affected private and social residential blocks by the end of 2018. Complete quarterly follow-up checks to ensure that remedial work is completed to the required standard. Checks should not cease until all work is completed.

- Stand by the prime minister’s commitment to fully fund the removal of dangerous cladding

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

- Explore options for requiring remedial works on affected private sector residential tower blocks

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- Take immediate action to identify privately owned residential tower blocks so that cladding and external panels can be checked

LANDLORDS

- Publish details of the combinations of insulations and cladding materials for all high rise blocks

- Commit to ensuring that removal work begins on all blocks with dangerous materials by the end of 2018 upon receipt of guidance from government

- Publish current fire risk assessments for all high rise blocks (the Information Commissioner has required councils to publish and recommended that housing associations should do the same). Work with peers to share learning from assessments and improve and clarify the risk assessment model.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out. Ensure assessments consider the external features of blocks. Always use an appropriate, qualified expert to conduct assessments.

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in the light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

- Adopt Dame Judith Hackitt’s recommended approach for listening to and addressing tenants’ concerns, with immediate effect

CURRENT SIGNATORIES:

- Chartered Institute of Housing

- G15

- National Federation of ALMOs

- National Housing Federation

- Placeshapers