You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

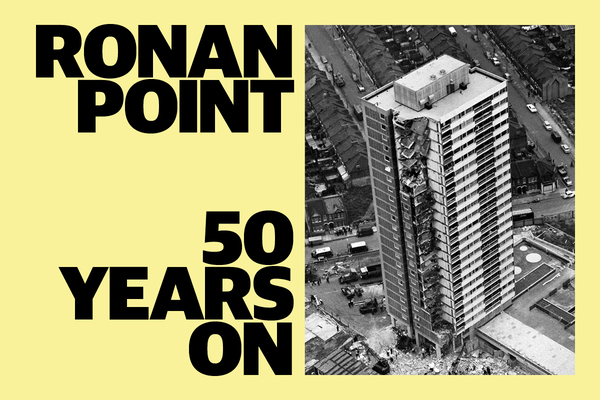

Ronan Point 50 years on: the dangers of large panel system construction

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the collapse of Ronan Point in east London, killing four people. Here is a piece from safety expert Sam Webb – originally published last August – warning about the construction method used in Ronan Point and in other blocks still in use today.

.

Throughout this week we will be publishing a number of articles on building safety to mark the 50th anniversary of the Ronan Point disaster

This piece was originally published on 16 August 2017

When World War II ended in 1945, Europe lay in ruins.

People needed homes. There was a need for radical new solutions and politicians seized on factory-made homes.

None more so than Sir Keith Joseph MP, minister for housing, whose family firm was Bovis.

A seven-minute standing ovation at the 1963 Conservative Party Conference assured acceptance of his programme to build 400,000 houses a year. These would be ‘system-built’ and would use unskilled, cheap labour, on site.

Sir Keith lured the London County Council with a serial housing contract of 1,800 flats.

“Large panel system (LPS) structures are like a ‘house of cards’.”

This Morris Walk Series contract was instrumental in encouraging the merger between Taylor Woodrow and Anglia Construction, which made precast concrete and specialised in high-quality concrete.

The new firm, Taylor-Woodrow Anglian, or TWA, bought a system safe to build up to four storeys. However, it modified the unreinforced H2 joints and took it up to 22 storeys at Ronan Point, a tower block in Canning Town, east London.

Large panel system (LPS) structures are like a ‘house of cards’ made of concrete panels. Floors and walls rest one upon the other, held together only by their own weight, until a lateral force is applied.

On 16 May 1968, a small gas explosion removed load-bearing flank wall panels, bringing down the south-east corner of Ronan Point, killing four people and injuring 17. The UK housing programme came to a shuddering standstill and it has never recovered.

A public inquiry was held. Work on all LPS sites stopped. Then, following a questionable test at Imperial College, work was allowed to restart.

In August 1968, a full-size loading test, ordered by Sir Alfred Pugsley, the engineer member of the public inquiry tribunal who was suspicious of the Imperial College test, revealed the critical H2 joint failed at 1.8 pounds per square inch of pressure.

The minister for housing ordered a complete shut-off of gas in all LPS blocks. We have been here before.

So too had the then-government. Two days after part of Ronan Point fell down, Cleeve Barr, chief architect, and Dr Chan, chief engineer, of the National Building Agency calculated that the H2 joint would fail at 1.4 pounds per square inch.

“All large panel system blocks suffer from bowing panels which create fire risks.”

Its secret report was sent to James Callaghan MP and the home secretary. To make this figure appear safer it was multiplied by 144 to give 200 pounds per square foot. That sounded so much safer – except they were the same force. Politicians and the building industry were in denial.

By the time the government report was published there were twice as many LPS tower blocks as there had been six months earlier. The report didn’t say how these blocks could be made safer; that wasn’t its purpose. Defined by narrow terms of reference, the main object of the inquiry was to keep politicians, of both parties, out of trouble.

An interim circular was issued. This stated if blocks could resist five pounds per square inch they were safe for gas. All failed.

“No one now knows with certainty who owns these blocks or where these blocks are.”

Politicians, faced with possible enormous compensation claims, lowered standards. If blocks could resist 2.5 pounds per square inch, then provided gas was removed they were safe.

There’s no doubt engineers at the time struck macho poses. Ledbury is no exception.

No one now knows with certainty who owns these blocks or where these blocks are. There is no definitive list.

All LPS blocks suffer from bowing panels which create fire risks.

In Ledbury, and other blocks, these gaps have been filled with mastic, masked by timber fillets. This is hardly cause for confidence.

For the tenants, this is a tragedy, and there is no magic wand to wave it away.

Sam Webb, member, All-Party Parliamentary Fire Safety and Rescue Group

Ronan Point: 50 years on

We have published a series of articles to mark the 50th anniversary of Ronan Point:

Are tenants being listened to on building safety? Tower block safety campaigner Frances Clarke questions whether Dame Judith Hackitt is really listening to tenants

The tower blocks that time forgot Fifty years ago councils were told to assess high-rise buildings that were similar to Ronan Point and strengthen them where necessary. So why are problems with some of the blocks still emerging?

One man’s 50-year battle to improve tower block safety Meet architect Sam Webb, who has been campaigning on safety in tower blocks since the disaster at Ronan Point

The worrying legacy of a disaster Jules Birch reflects on what we can learn from the Ronan Point disaster

Watch a new film about Ronan Point Filmmaker Ricky Chambers, whose grandparents and mother lived in Ronan Point, has made a film telling people’s stories of the ill-fated block. Watch the film and read Mr Chambers’ comments on why he made it

The dangers of large panel system construction Building safety expert Sam Webb explains why the system of construction used at Ronan Point was flawed, and how it was used in other buildings still occupied today

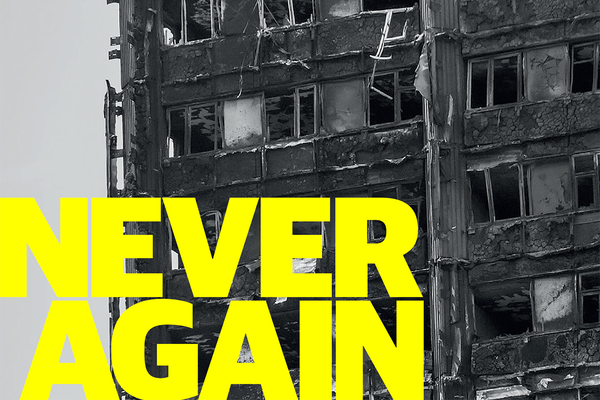

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.