Invisible children: how poor conditions in temporary accommodation are damaging young lives

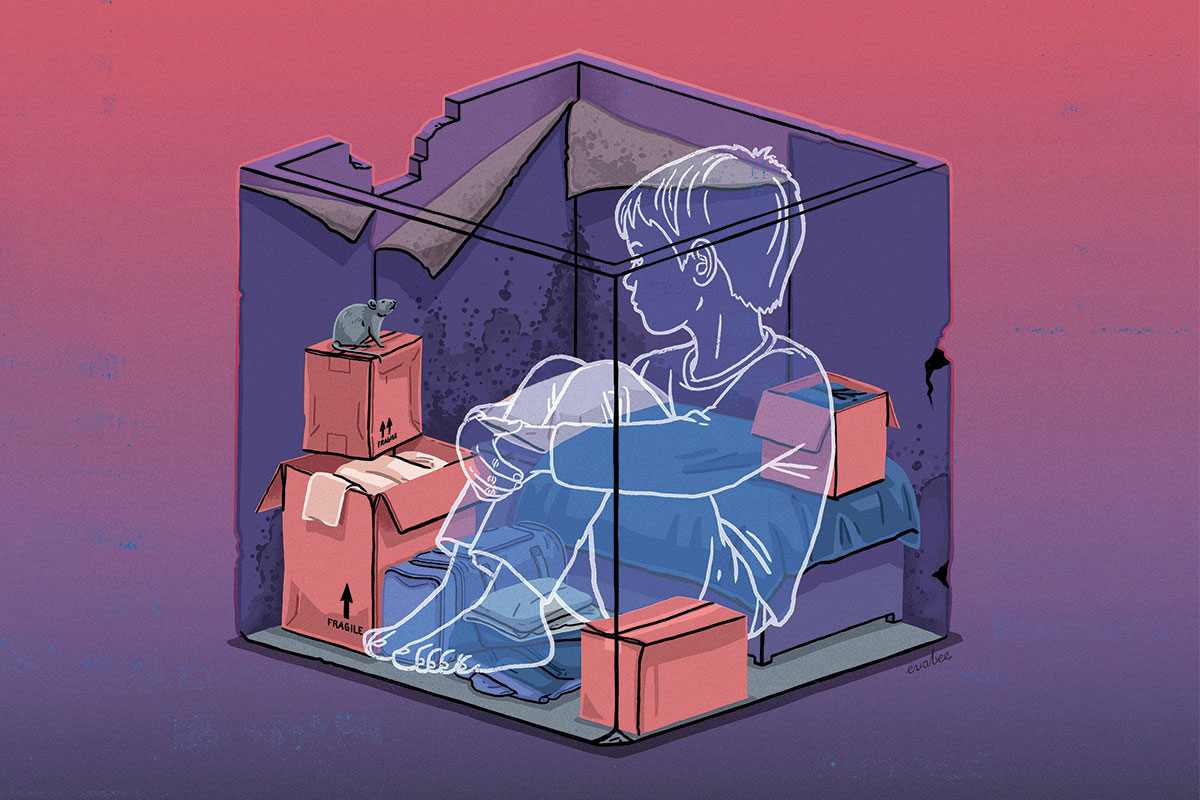

The number of children in insecure temporary housing is growing. But the impact this is having on their health, development and life chances still remains largely unknown and unrecorded. Keith Cooper reports. Illustration by Eva Bee

When thousands of children start school next month, an alarming number of them will arrive dirty, tired and underdeveloped, far from ready for that vital first year. These children will all have one thing in common: they will have spent their early years in temporary accommodation, arranged by a local authority’s homelessness department.

Some will have grown up confined to a small room, shared with the rest of their family, with no space to play, walk or socialise with other children. Others might live in mixed housing blocks alongside drug users, where their older siblings prefer to use a potty in the cupboard rather than queue in the corridor for a shared toilet.

And while the government can put a figure on the total number of children in temporary accommodation – 131,370 at the last count – the impacts on their health and lives remain largely unknown and unrecorded.

“Nowhere in the healthcare system do we ask whether kids are in temporary accommodation or track them,” says Laura Neilson, a medical doctor who founded and now heads the Shared Health Foundation (SHF), a charity funded by The Oglesby Charitable Trust to help homeless families in temporary accommodation in Greater Manchester.

Developmental delay

What is known is that temporary accommodation contributed to 34 child deaths between April 2019 and March 2022, although the role housing played is found in the fine print of serious case reviews rather than in newspaper reports. This figure comes from an analysis by the National Child Mortality Database (NCMD) and, because of the way information is recorded, it is likely that there are more undocumented cases.

So what do we know about the impacts of temporary accommodation on the health of babies, infants and children? And what can councils and social landlords do about it? Clinician-led organisations like SHF and research group the Champions Project have begun gathering data, prompted in part by the pandemic and the lockdowns that kept us all in our homes.

“We realised that things were going to be a lot worse for children,” says Monica Lakhanpaul, professor of integrated community child health and honorary consultant paediatrician at the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health. She is the principal investigator of the project, which is run by UCL and De Montfort University.

“There would be increased poverty, people losing their jobs. It would have a long-term effect. But a lot of the interesting things that we found are not related to the pandemic, and our work has continued.”

“Children were often stuck in housing with not much space to play, leading to development issues. They can’t walk in such tiny rooms”

The Champions Project looked at children up to the age of five. Its findings are based on interviews with health professionals and 60 families in temporary housing, mainly in Manchester, Leicester and London.

One of its most concerning findings was malnutrition. “There’s this combination of poor housing and poverty,” Professor Lakhanpaul says. “It is difficult for families to keep food cold, because they don’t have fridges and they lack the facilities to cook. Food is put outside windows to keep it cold and they use Pot Noodles or biscuits for meals. They’re called ‘belly fillers’.”

Without washing machines and with long waits for bathrooms in shared accommodation blocks, families often find it hard to keep clean. Researchers found a lot of tooth decay in children in temporary housing, due to difficulties accessing dentists, as well as breathing problems stemming from damp and mould in tiny, poorly ventilated rooms. Cockroaches and vermin also put children at risk of asthma and skin infections.

Then there is the stark impact on child development. “Children were often stuck in housing with not much space to play, leading to development issues. They can’t walk in such tiny rooms. Parents are frightened to send their children to playgrounds, for fear of where some are located,” says Professor Lakhanpaul.

“Some children can’t even potty train in these sorts of houses,” she adds. “They are put in non-child-friendly accommodation with people who are drug addicts or other adults who they may find scary. Older children have been known to go to the toilet in a potty in the cupboard, because they can’t get to the shared toilet or have to wait in long queues.”

As a consequence of living in such conditions in their early years, young children in temporary housing often go to school tired, dirty or so poorly developed that they are not even ready to start reception, she states.

“The schools think they are neglected by their parents, when, in fact, it is the environment they are in.” Parents should be supported, not blamed, she adds. “We need to prevent these problems from happening, rather than the current system, which leaves us trying to unravel them.”

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities says the long-term use of B&Bs for families with children is unlawful and that its homelessness advice and support team offers help to councils to end the placement of families in such accommodation for longer than six weeks. However, at the last count, there were 1,840 families with children that had been living in B&Bs for more than six weeks in England.

“Health visitors are critical, because they can find out when a child is underweight or has developmental delay”

Professor Lakhanpaul hopes the Champions Project will increase the visibility of children in temporary accommodation, but fears that the national decline in the number of health visitors means fewer problems will be picked up. “Health visitors are critical, because they can find out when a child is underweight or has developmental delay.”

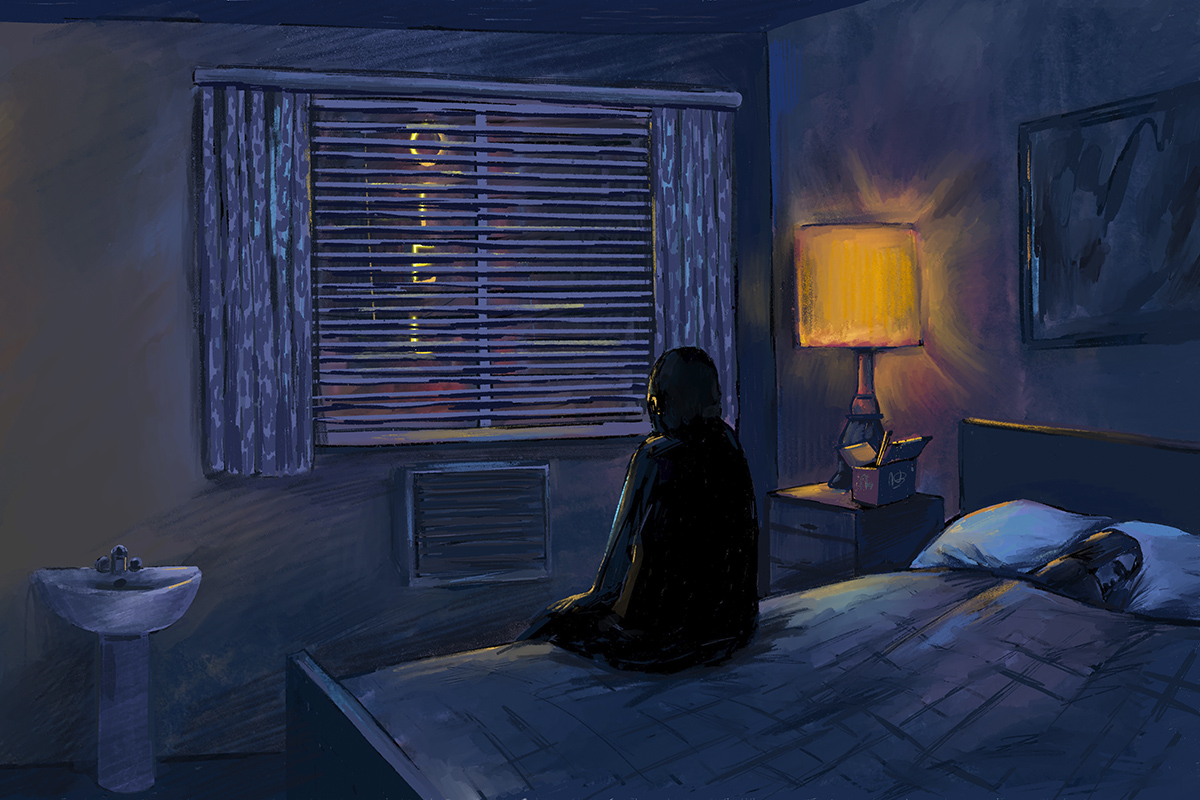

The psychological effects of poor housing conditions are even less visible than physical impacts such as bug bites and breathing difficulties. They show up in older children as they respond to constantly shuttling between hotel rooms, B&Bs and accommodation blocks, which has become part of the itinerant existence of so many homeless families.

Sofia* (name has been changed) and her teenage son were moved between seven different Manchester hotels in 10 days after she left her abusive husband and job earlier this year. A self-contained flat in a women’s refuge – a five-hour drive from her local area – was eventually found for them.

“It was a really difficult time,” she explains through an interpreter. “My son was really shocked when I picked him up from school and told him we were staying in another hotel. Before, where we lived, he had friends.

He felt fine with his peers. Now he is suffering a lot and I feel bad about his situation. I feel like it’s my fault.”

Sofia says her son is still out of school and that she wants to return to her local area for his and her own good. “But how can I do that? I don’t have any money. I don’t have a house.”

Making temporary accommodation better

Separate reports in January this year from the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Households in Temporary Accommodation and the Champions Project called for a legally enforceable minimum specification for temporary accommodation to include: basic kitchen appliances; beds for all members of a household, including babies; adequate, safe space for children to play and learn; and no mixed households in B&Bs, hotels and apartment complexes. Other recommendations in the reports include:

- Control of vermin, mould and pollution

- A notification system to inform health and education services about homelessness

- Checks on the maximum length of stay for children in unsuitable accommodation

- Community service navigation advisors and information packs to help families access information and support, especially when rehoused in unfamiliar neighbourhoods

Sources: All-Party Parliamentary Group for Households in Temporary Accommodation; and Champions Project policy brief

SHF hopes to increase the visibility of health problems related to accommodation by encouraging parents to report them. “We tell mums to show their children’s bedbug bites at their immunisation appointments, ask for them to be documented, and for it to be written on the notes that they’re living in temporary accommodation,” says Angie Ouattara, its maternal health lead. “We tell them it’s OK to complain, to say this is not OK, because so much of this is hidden and not talked about.”

However, many parents are reluctant to report problems. They fear being referred to social services for being a “bad mum”, Ms Ouattara says.

“Families in these situations have often not had brilliant experiences with professionals,” adds Dr Jen Davies, a clinical psychologist who also works for SHF.

To build trust, the foundation runs stay-and-play sessions at a GP practice in Manchester. “Lots of the accommodation has no communal space for parents to gather, so we give them opportunities for peer support,” says Dr Davies. “It’s also a space with toys, so it gives them a chance to delight in their children playing, and allows us to have more in-depth conversations with them. The key thing in this work is building up safe enough relationships for families to feel able to trust us.”

Unsafe environment

Ms Ouattara says the “chaos” of repeated displacement means healthcare “goes out the window” for many families.

“Nothing is permanent; there is no stability where they’re living. They have so many other priorities, in the sense of just feeling safe and having somewhere to be.”

The consequences of this situation are worrying: GPs remove families from their lists when they move out of catchment areas; children are discharged from clinics because they fail to turn up for appointments after letters are sent to old addresses; babies miss immunisations. “These kids just vanish, then reappear a year or so later,” says Dr Neilson.

SHF’s work focuses on the first 1,001 post-conception days of the lives of the children they see. It is a critical period that runs up to age two and sets the long-term foundation for emotional and physical well-being, according to experts and the Department of Health and Social Care.

But SHF is also very concerned about the risks to older children when they are rehoused in temporary accommodation with single homeless men. “We’ve got lots of evidence of teenage girls being propositioned and mums being asked if they’ll have sex,” says Dr Neilson.

“It’s just not a safe environment. We would never put kids in places where we hadn’t carried out [Disclosure and Barring Service] checks. I work in Oldham and Rochdale, where we’ve just had these grooming scandals. This looks like a recipe for the next one.”

Dr Neilson supports a ban on mixed accommodation for homeless households. It’s one of several recent recommendations to make temporary accommodation safer and healthier (see box above).

“Every local authority we have a conversation with tells me this is not a problem. They say, ‘It is all fine,’ so you just go round in a loop”

But there is an immediate health risk that frustrates Dr Neilson even more: the lack of suitable sleeping arrangements for babies and infants. “Cots are as cheap as chips, but we keep putting babies into temporary accommodation without providing them. That is a massive risk for sudden, unexpected death,” she says.

A “strong link” between SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome) and sleeping arrangements was identified last year in a study by the NCMD. It found that, in 2020, more than half (52%) of 124 unexplained deaths of sleeping infants had occurred when their sleeping surface was shared with an adult or older sibling.

“Every local authority we have a conversation with tells me this is not a problem,” Dr Neilson says. “They say, ‘It is all fine,’ so you just go round in a loop. They [say they] are not responsible; the landlords are responsible. But nobody takes responsibility.”

SHF hands out cots when it can. “When we see it, we’ll fix it, but this is just a sticking plaster. What we really need is a shift in policy and practice,” Dr Neilson says.

One thing that could help is finding a better way to record the type of accommodation these children are living in. Currently, researchers have to rely on respondents supplying information about accommodation in a free-text box. The NCMD is now considering adding specific questions about accommodation on their data collection forms.

While death is the most extreme consequence of poor housing conditions, it could also, tragically, soon become one of its most visible signs in babies, infants and children. “The chaos of temporary accommodation is hard for some of these families,” says Ms Ouattara. “And the tragedy of it all is that, sometimes, it does end in deaths. That’s why SHF is here.”

Aims of our Build Social campaign

For all political parties to commit to funding a substantial programme of homes for social rent in their manifestos at the next general election. This includes:

● 90,000 social rented homes a year over the next decade in England.

● 7,700 social rented homes a year in Scotland.

● 4,000 social rented homes a year in Wales.

Inside Housing commits to:

● Work to amplify the voices of people who need social housing, including families living in temporary housing and overcrowded conditions.

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters