You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The fall and rise of social rent

Will the comeback of state-funded socially rented housing deliver the homes Britain needs? Peter Apps reports

In the 12 months to April 2011, at the height of the recession, a shade below 40,000 new socially rented homes were built in England.

By April 2017 this figure had collapsed, undergoing an 85% fall to a negligible 5,900 units – 2.7% of overall housing supply and the lowest figure since records began.

See here:

But this, it appears, may be a nadir.

Social rented housing is making a comeback. The next set of government funding programmes – in London and the rest of England – will include homes for social rented housing, supported by grant rates of up to £100,000 of public money per unit.

Meanwhile, Homes England, the government’s delivery agency, will use its new strategic development partnerships with housing associations to actively push for increased levels of social rented housing in the tenure mix.

This marks a total reversal of the agency’s role (under its previous branding as the Homes and Communities Agency) when providers were required to commit to converting social rented homes to newer affordable rents in order to qualify for grant.

So as this new era of state-funded socially rented housing kicks off, Inside Housing looks back at how we reached this position and asks whether the new dawn will actually deliver the numbers we need.

The fateful decision to move away from social rented housing was taken in the very early months of the coalition government.

New chancellor George Osborne was preparing his first major cuts to state spending, and housing was in the crosshairs. It is understood the message from central government to the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) was that the Treasury’s intention was to end state funding for affordable housing altogether.

This would have come at a time when most housing associations had not developed the cross-subsidy businesses they run today and could have had fatal consequences for the sector’s development.

“The counter option to affordable rent was nothing at all,” says one sector source. “That would have resulted in a very different position. Some housing associations might have kept developing, by ramping up their outright sale, and others might have picked up a bit of Section 106. But many others would probably have wound down completely and once you stop it might have taken a generation to build that capacity back up.”

With this threat in mind, it was left to the DCLG to come up with a counter proposal. And what the department suggested was the ‘affordable rent’ regime. This proposal, worked up in a matter of days, was to crank up the rents charged in new rental homes to up to 80% of the market rate and convert old social housing units to this new tenure when they became empty.

This proposal was attractive. It didn’t require a new rent formula, so could be introduced swiftly and was compliant with rules about state aid due to being below market.

Crucially, for Treasury officials, it also meant a giant cut to subsidy could take place, with the additional rental income allowing housing associations to take on more borrowing to fund development.

Despite putting up rents in the social sector, the policy was actually pitched to the Treasury as neutral in terms of housing benefit, as the tenants who occupied these homes would otherwise have been claiming more in the private sector.

Mr Osborne went for this proposal, cut the housing budget by 60%, and ‘affordable rent’ was born.

There are those who say this was about more than economic necessity. As Steve Douglas, chief executive of housing consultancy Altair and former boss of the Housing Corporation – which ran government funding programmes – explains, it was also a question of ideology.

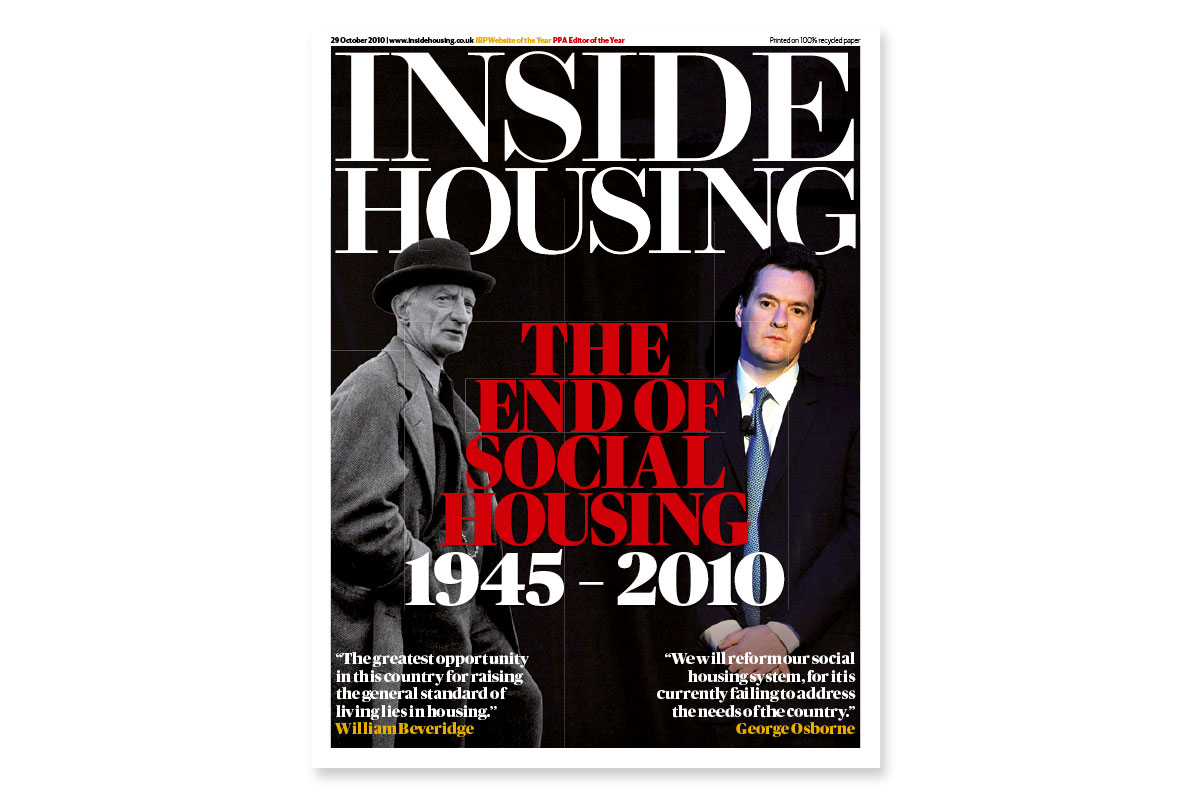

Inside Housing cover from 29 October 2010, when George Osborne scrapped grant funding for socially rented housing

“You need to see this within the overall debate about who social housing is for. So long as we don’t have enough housing supply, there’s always going to be a rationing of where public subsidy goes, that will always be driven by political ideas,” he says.

“The government and the particular ministers of the time that led the policy believed state-funded housing should be for a different client group – it shouldn’t be for people who are on the fringes of the labour market, and instead it was seen as an intermediate product for people to take a step up into homeownership.”

On one measure, affordable rent was a success. It certainly kept delivery going with 110,000 such homes built to date, and a peak of more than 40,000 in 2014/15.

For a policy developed against the clock, in the face of a government planning to axe affordable housing budgets entirely, this can be considered a not insignificant victory.

But on the other hand, it has been a disaster. In a labour market with stagnating wages and soaring rents, in many areas of London and the South East the rents are now out of reach for those on lower incomes. In London, they average around 65% of market rents – which would be at least £1,400 a month for a three-bed in most of the capital; across much of the South East it would be more than £1,000.

“The debate has changed to a view that it takes a variety of tenures to solve the housing crisis.” - Steve Douglas, Altair

Meanwhile, the policy of conversions combined with a Right to Buy scheme that allows socially rented homes to be replaced with affordable properties has seen around 150,000 social rented homes ‘lost’ since 2013, according to analysis by the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH).

Crucially, a series of welfare reforms have also undermined the policy. “What many of us didn’t realise [in 2010] was the impact planned welfare changes would have on people’s ability to pay these rents,” says Melanie Rees, head of policy at the CIH.

Most pertinently, the cap on overall benefit entitlement has left those reliant on benefit unable to afford affordable rents in much of London and the South East. This leaves them reliant on the bottom end of the private rented sector – with its lack of security, notoriously low standards and, ironically, higher rents which push up the overall benefit bill. Housing benefit spend rose from £16.9bn in 2010 to £21.3bn in 2017, with around £9bn a year going to private landlords.

So what of the current changes? What is clear is that the sector is happier with this position than the one it faced in 2015 when David Cameron’s majority government shifted funding away from even affordable rented housing to homeownership products.

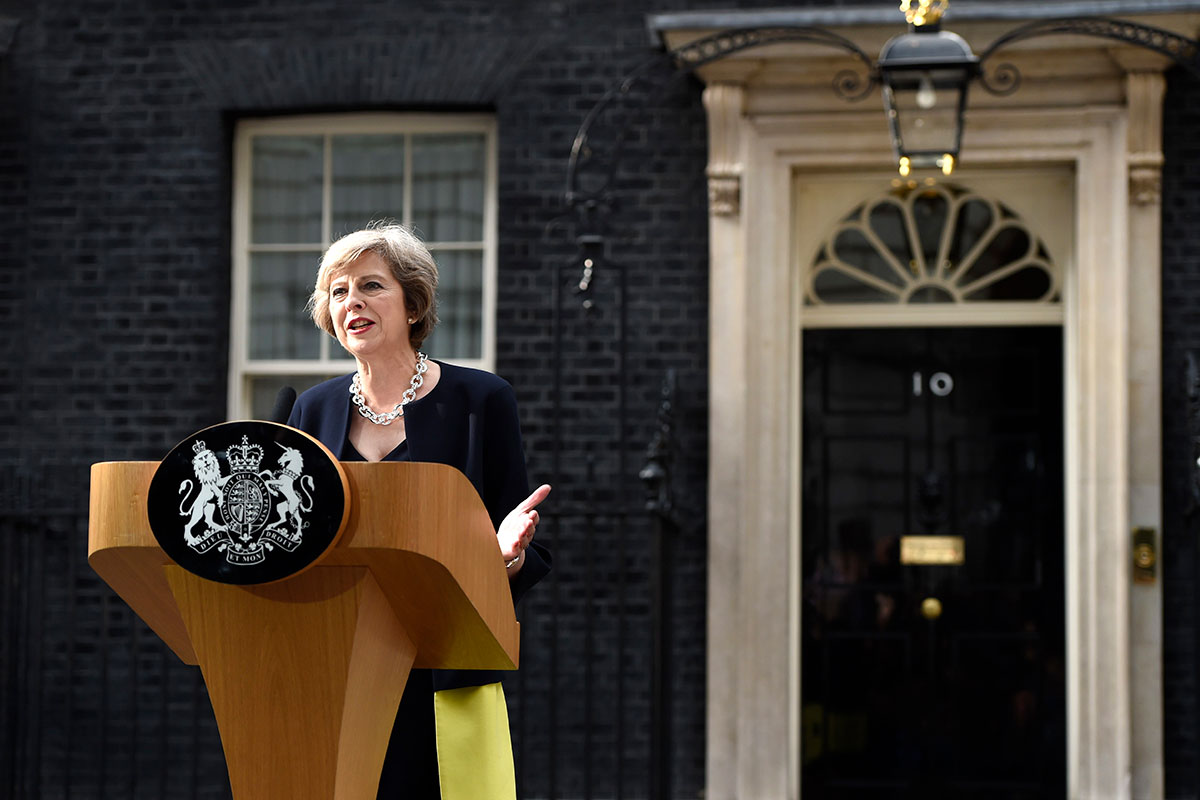

This position has been steadily chipped away at by Theresa May’s government – culminating in the announcement of £2bn which will at least partially fund socially rented homes by the prime minister in October, harvested from the defunct Starter Homes initiative, and the strategic partnerships announced last week.

Theresa May talks about her focus on “just about managing families” in her debut speech as prime minister (Picture: Getty)

London mayor Sadiq Khan will also be allowed to fund homes at ‘target rents’ (the rate social rents are converging towards) in his new grant programme. This would have been an unlikely option under Mr Cameron’s regime.

There are several driving factors here, which Mr Douglas identifies as changing personnel in the key positions and politics – particularly the shift in focus towards “just about managing families” instituted by Ms May and the increased pressure to take the housing crisis seriously driven by the rise of Jeremy Corbyn and the fallout from the Grenfell Tower disaster.

“The debate since the Housing White Paper has changed to a view that it takes a variety of tenures to solve the housing crisis,” he says. “The whole language and narrative at the top of government has become much more about recognising that there is a need for a variety of tenures.”

The initiatives themselves have been broadly welcomed. Chief executives of associations known for their commerciality, such as Elaine Bailey of Hyde and David Cowans of Places for People, tell Inside Housing that the new strategic partnerships will likely see them up the amount of social housing they are building.

“[Money] is still heavily weighted towards homeownership initiatives,” Melanie Rees, CIH

But the first criticism of the plans is that they still represent a fringe of the government’s £9bn housing budget, and an even smaller fringe of its overall spend on housing programmes, including Help to Buy, which the CIH calculates at around £40bn through to 2020/21.

“We still think they could go further – without necessarily spending any more money, but redirecting the way money is spent,” says Ms Rees. “It is still heavily weighted towards homeownership initiatives.”

The government – both City Hall and Westminster – has not committed to targets. But with the amount of money on the table this is not going to be a return to 40,000 social rented units a year. The low tens is a more realistic, but still optimistic, bet. The money is also earmarked only for areas of ‘high housing demand’ – calculated according to private rent levels – which means towns such as Sheffield with vast housing waiting lists will likely miss out.

Then there is the ongoing sale of homes under the Right to Buy (currently averaging between 15,000 and 18,000 a year) and the ongoing conversions, which mean this programme has to reach a substantial speed in order to simply stand still.

Nonetheless, for fans of social rented housing it is a small step in the right direction and not one that many would have predicted three years ago.