How social landlords are responding to high-rise window danger

Last month, two children fell to their deaths from the upper floors of two blocks of flats. The cases are under review, but are already sparking questions about window safety and landlord responsibility. Hannah Fearn reports

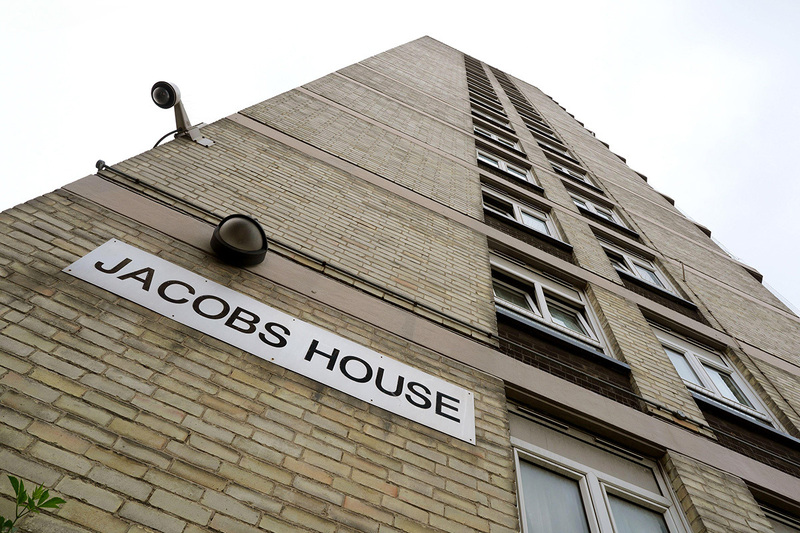

On 16 May, five-year-old Aalim Makial Jibril fell to his death from the 15th floor of his high-rise home in Plaistow, east London. The coroner found his death was a tragic accident caused by a fall from a window. Aalim’s family told journalists his mother had complained about the window to Newham Council about five times, warning that it was unsafe with young children in the home. Newham is now carrying out a full investigation of the tragic event.

Just days later, a 12-year-old boy, Renoy Ellis, died after falling from an upper-floor flat in a tower block in Kennington, south London. Police said there was “nothing to indicate the incident was suspicious” and investigations are continuing into whether the fall occurred from a window or balcony.

Both cases are still under formal review, which will involve a close look at the repairs records and risk assessments for those properties. But with two deaths of a minor in such quick succession, how likely is it that we will see another?

Very likely, warns Eleanor Solomon, a partner at Anthony Gold Solicitors who regularly acts on disrepair cases on behalf of social tenants. The reason, she says, is two-fold: there is no regulation in place to require social landlords to do routine maintenance to prevent window disrepair that can lead to dangerous situations that precede a tragedy; and the management of repairs services is another source of risk.

Poor record-keeping

In Newham, the coroner’s inquest will not get under way until October. However, early indications suggested the council’s repairs register said the job had been completed when that wasn’t the case, despite the mother’s repeated complaints. If that is true, it would not be an outlier, Ms Solomon says. On the contrary, it is a common finding present in most disrepair claims she handles.

“Almost throughout my entire career of working in disrepair cases, it’s an incredibly common thing to look at records and it will say it’s been done when it hasn’t been done,” Ms Solomon says.

“It happens in every single case. Sometimes people will come, but haven’t done anything; sometimes nobody has come and the computer will say something was done. As for falls, there’s not much routine checking of window safety at all. There’s a void check, and sometimes that’s done well and sometimes things are missed – and that’s it,” she says.

The situation on repairs record-keeping has worsened as funding cuts have tightened finances in the past decade, she adds. Many already large landlords have merged with other big providers to seek financial efficiencies. They have often outsourced their repairs in the process. That means multiple agencies and computer systems are involved in the logging and tracking of every repair. Repair records also rarely use data to highlight where there are multiple complaints of a similar nature in the same block, indicating that the problem is a potential risk for every tenant.

“There is not one person overseeing it and saying, ‘I can see this is a recurring problem,’ or, ‘Everyone in the block has been complaining about this,’” Ms Solomon says.

The situation means both councils and housing associations are often unaware of the state and security of their windows – even in high-rise blocks – and turning to their own datasets won’t necessarily illuminate them. It makes it almost impossible for them to quantify how much it would cost to retrofit windows with security devices, even if they wanted to do so.

This matters because, soon, they may be forced to do it.

In May last year, a coroner issued a warning to the housing secretary over window security after an adult man fell to his death from the 16th floor in Stretford, Greater Manchester. Alison Mutch, senior coroner for Greater Manchester South, wrote to Michael Gove to say she found it “a matter of concern” that only education and healthcare buildings, as well as those provided for vulnerable adults, required window restrictors to be fitted in high-rise developments. For general needs social homes, she confirmed, “there is no current requirement to retrofit fixed window restrictors”.

With the Decent Homes Standard under revision – and a change of government to factor in, too – this intervention may prove critical.

Over the years, some housing associations have revised their repairs and management processes to try and get a better handle on safety issues. As far back as 2010, Stevenage Homes, an arm’s length management organisation, spent more than £100,000 fitting restrictors to every window on the second floor and above of its 75 developments of three storeys or higher. Its environmental health officer at the time concluded windows should open to a maximum of 100mm.

Clarion Housing Association has a process in place so that every high rise above seven storeys has a named building safety manager, providing a single point of contact – and, ultimately, overall responsibility – for security issues, including window operation.

However, the picture across the sector is very opaque. Inside Housing contacted 16 large housing associations to ask them about their plans for monitoring and managing window repairs in light of these deaths, including whether they were considering retrofitting window security measures. We were looking for some examples of best practice to share with the sector.

The response painted a bleak picture. Every single one declined to participate; many stated they would share more when there was confirmation of a new Decent Homes Standard.

Behind closed doors, there is much concern about the impact that huge cuts in funding for social housing are having on routine repairs, particularly as the political agenda is focused very heavily on issues of fire safety and damp and mould. Many housing associations are still focused on submitting their own reports on safety to the new Building Safety Regulator.

We spoke to councils during the pre-election period, which restricts how much local authorities can say in public during a general election campaign. However, one building safety officer working in local government confirmed there was currently “no workstream” specifically in place for window safety in social housing, and there was even confusion about overlapping expectations between regulators, with the Regulator of Social Housing and the Building Safety Regulator both covering high-rise developments.

In this environment, “windows just aren’t getting looked at in large order”, he said.

More official guidance needed

The lack of appetite for large retrofit window safety programmes may also be based on a sensible reason: climate change is leading to temperatures inside high-rise flats increasing every summer, meaning window restrictors, for example, may not be proportionate or desirable, or even perform their intended function, given they can often be forced (overridden).

During the pandemic, there was one death and other incidents after air conditioning units broke down in hotels housing refugees and windows were forced open, overriding safety catches, to make the temperature inside each room safe.

“There can always be human error. There isn’t a huge amount that councils or building owners can do if tenants themselves force open those windows,” he said.

“But if you’re a building owner or local authority that is concerned about your individual safety cases, then it does make you think, ‘When are we going to get around to those matters?’”

A spokesperson for London Councils said boroughs’ “top priority” was ensuring that all residents were safe in their homes.

“As social landlords, boroughs are committed to taking prompt action on building safety concerns raised by tenants. These recent incidents have highlighted the importance of window safety as part of boroughs’ ongoing work to review and improve standards in their housing stock.”

But residents who are members of the London Tenants Federation (LTF) disagree that action on their complaints, particularly around issues that affect safety, are prompt.

LTF support worker Joseph Jones says that although the recent highly publicised deaths have not led to an immediate rise in complaints about window safety, the tenants he represents are aware that the focus on damp and mould is leading to other repairs being classed as less important or urgent. For the tenants’ comfort and safety, that may not be the case.

“When a council or a landlord has limited funds and then is being told by central government, ‘You must do this’ and there is no additional funding coming in to do that, then they’re looking for how best to allocate those limited funds.

“Like the whole public sector, since 2010, landlords have been starved of cash in a way that has not been experienced in decades, and that has a knock-on effect,” Mr Jones says, with some sympathy.

After the Grenfell Tower fire, recommendations were made in Phase One of the inquiry that personal emergency evacuation plans should be drawn up for every social tenant with a disability. After a private meeting with landlords, the government scrapped that recommendation because it was too expensive for cash-strapped councils and housing associations to deliver.

Mr Jones believes, similarly, window improvements will not follow from these recent tragedies. He also warns, like Anthony Gold’s Ms Solomon, that extensive sub-contracting leads to higher risk and longer delays. “It leads to non-repair and it could lead to, unfortunately in some cases, the tragic death of people. Bringing market forces into the social housing sector has made things worse, not better.”

Social landlords would like more guidance. As we enter a new political period, the National Housing Federation (NHF) says the government “has a clear role to play” in setting regulation to keep tenants safe in their homes. Alistair Smyth, its director of policy and research, says NHF members would support a review of whether window restrictors should be required as a basic minimum safety standard for upper-floor properties and whether any new requirement should be introduced through a revised Decent Homes Standard.

“We fully support the review of this and encourage whoever forms the next government to prioritise moving this forward after the election,” Mr Smyth says.

He adds that “housing associations have been increasing the frequency of their stock condition surveys’’ and employing other methods to carry out regular checks inside all properties.

Landlords seem unwilling to share these methods publicly, and changes in regulation will, inevitably, take time, as a new government settles in.

New legislation may not even be desirable or proportionate, Ms Solomon says, warning it may simply cause new complications. Window restrictors across a full block could create new fire safety concerns, for example. The reduction of risk has to come from within the organisation, she says. If a tenant warns there is a potential issue, why isn’t it being acted on?

“It’s so cheap and quick to fit or replace a window restrictor. That is just one person going round and it costs almost nothing. It’s easy.”

Recent longform articles by Hannah Fearn

A timeline of housing history – the 2010s to present day

In our final trip back in time to celebrate Inside Housing’s 40th anniversary, Hannah Fearn, Jess McCabe and Faima Bakar revisit the 2010s and 2020s, and look at how we reported on the big stories

Andy Hulme moved from the banking sector to head up Hyde Group. He talks to Hannah Fearn

An app that connects homeless people with donated postal addresses sounds like it would be simple and helpful for people to set up benefits and do other life admin. It was more of a success than anyone could have expected. Hannah Fearn reports

Sign up for our asset management newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters