You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

How the housing crisis is affecting the sector’s own staff

A lack of decent, affordable housing is also affecting social landlord employees. Jess McCabe investigates. Illustration by Nick Chaffe

Social landlords are proud of their social mission: to provide decent and affordable housing. So what does it mean if some of their own staff – tasked with that very mission – are struggling to keep a roof over their heads?

Earlier this autumn, the chief executive of a large London housing association made a passing comment during an interview with Inside Housing. She had discovered that members of her own staff were living in insecure housing.

“If they were in the social sector we would consider them homeless.”

“They’re all in shared houses, or even shared bedrooms, or living in places that are disgusting,” said Kate Davies of 32,000-home Notting Hill Housing. “If they were in the social sector we would consider them homeless in those circumstances.”

It sounded shocking that a housing association’s staff could be considered effectively homeless by its chief executive.

Inside Housing wanted to investigate if this was a one-off, perhaps focused on the struggles of London life. Or was it a widespread phenomenon? We launched an anonymous survey to find out more.

What we discovered was startling. Members of staff in housing associations, councils and homelessness charities are going into work every day to contribute to the running of Britain’s social housing – and then coming ‘home’ to face the hard realities of the modern housing market (see below).

In the words of one housing manager, “I have been street homeless while working in the sector, which made me feel close to a nervous breakdown.”

Stories told anonymously to Inside Housing (see quotes below) include eviction, homelessness, being stuck in large flat shares, and adults living with their parents well into their 30s, along with numerous struggles to pay the rent or move on with life decisions, such as having children, because of housing costs.

In total, 561 housing staff responded to Inside Housing’s survey, one of the highest ever responses to such a request by this magazine. Respondents ranged from junior administrative staff to chief executives, on salaries from £9,000 to more than £100,000, and included many mid-level housing officers and managers. Responses flooded in from every region of England and every country in the UK.

First, we must put into context that such housing problems do not affect the majority of respondents. A full 68% said they are satisfied with their housing situation. Indeed, 59% of respondents own their home, while a small number (2.5%, or 14 individuals) are in shared ownership. Another 12% live in social housing themselves. This is not always a cakewalk – particularly for staff whose employer is also their landlord – but these respondents are, by and large, happy with their lot.

Most of the problems were reported by the remaining one in five housing staff who live in privately rented homes, temporary housing, shared housing, or with friends or family. Some of these respondents were at the beginning of their careers on salaries well below the national average salary, which is £27,271 this year.

“We have members who rely on food banks and mini cabbing in the evening.”

But earning above this average, and having a managerial job, was not an absolute protection either. Even homeowners on a high income are affected by housing problems: one chief executive reported that their own child was sofa-surfing.

The majority of housing staff spend more than 30% of their salary on rent or housing costs, while 7% spend more than half their earnings on putting a roof over their head.

Many respondents told us of struggling to pay the rent – or prioritising their rent but struggling to afford food as well as things that, while not essential, are part of a satisfying life. “Some months I’m not left with much or anything after my rent goes out,” one told us. Another simply said: “I just go without everything else.”

It’s a story that is familiar to John Gray, a housing officer in east London who is Unison’s National Executive Committee member for the housing sector. “We have members who rely on food banks and mini cabbing in the evening and weekends to support their families,” he says.

Staff in the capital are particularly affected, and some are “fleeing London” for less expensive parts of the country, Mr Gray adds. He has submitted a motion calling for action on this issue to Unison’s community conference in February 2018.

Several respondents admitted to feeling despondent and even depressed about their housing. “Good housing makes for a good family life,” one noted. Of course, the converse is that a lack of good housing is not conducive to good family life.

“Depression, unable to imagine a future, no possibility of raising a family,” summarised one manager in the East of England.

When shown the results, Alison Inman, president of the Chartered Institute of Housing, said: “I wonder what the consequences are when staff feel that the tenants they are working with are housed more securely, and in far better maintained homes than they are able to access themselves?”

“I feel like people [living] in social housing should be more appreciative of what they have.”

When we asked housing staff about how their own housing conditions affect how they feel about their job, a minority simply said: “It doesn’t.” But for most there is a direct connection.

Some of this is good, such as for one staff member who commented: “My job keeps reminding me of how lucky I am to have a safe, secure home, unlike others who do not.”

But the feelings stirred up are not all positive. Two respondents simply said they felt “angry”.

Others admitted resentment. “I feel like people [living] in social housing should be more appreciative of what they have, rather than expecting the housing association to fix every little thing that goes wrong,” said one administrative staff member, who lives with their mother. “If I was a resident, I would be grateful.”

Another said: “I love my job and what we do is so important but it’s frustrating that at 35 I still can’t afford something more permanent than a house share and because of my circumstances will never qualify for any useful help.”

Yet another comment was: “Sometimes you see residents who have [a] higher standard of living than you yet [are] still getting state aid in the form of social rents.”

Those who had experienced housing problems and been directly refused help by their employer were particularly disillusioned.

Speaking to Inside Housing about these results over the phone, Ms Davies of Notting Hill Housing is not surprised. But what can landlords actually do? Is the answer higher pay?

On the one hand, Ms Davies says that London employers in particular may struggle to retain staff if they can’t afford to live in the capital. The problem is real, she says, with “people in couples and even with kids in shared housing”.

But it may not be possible for landlords to solve their staff’s housing problems by raising salaries alone. “If the average salary is £26,000 to £27,000, that only sustains £700 a month [on housing costs]. Wages would have to be doubled to make any difference whatsoever,” Ms Davies notes.

If that is unlikely to happen, should employees despair of their employers doing anything to help?

Ms Davies argues not, pointing out that Notting Hill runs a tenancy deposit loan scheme for staff, which can help with one large cost of housing in the private rented sector.

Since April 2015, 19 employees have taken up the loan, with five currently making repayments. Landlords also should ensure that their staff are not excluded from renting or buying, or applying for schemes their employer runs.

Even if these measures are not going to be enough to solve all the housing problems of staff, they might help people working in housing feel less excluded, and as if the sector has no answer to their housing woes.

The results of this survey are in many ways a challenge to social landlords.

Knowing that their own staff members are suffering from the housing crisis, what – if anything – are they going to do about it?

Housing staff speak out

The below are all quotes from staff working in the social housing sector:

“I suffer from mental health problems after being served so many Section 21 notices when a landlord is ready to sell. I live in London and have had 14 addresses in 13 years. I have had to seek counselling for this and was medicated in the past. My two-year-old daughter has had four addresses already.”

“I always have low-level anxiety about security. I feel unable to better my situation – trapped, it exacerbates my depression and feelings of dependency.”

“My job makes me appreciate how lucky I am and how fragile housing security can be.”

“I ended up on antidepressant tablets for depression and anxiety. I was breaking down in tears and my company didn’t support me or help to rehouse me when I asked for help.”

“I’m not paid enough to afford a decent home event after working full time. It makes me realise how close I am to the people I support (one month’s salary away from homelessness).”

“It affects all aspects of your life, because you do not have your own personal space or privacy, especially when you’re living in an overcrowded flat.”

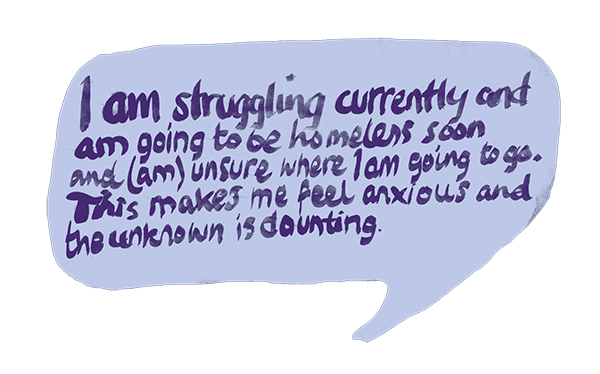

“I am struggling currently and am going to be homeless soon and am unsure where I am going to go. This makes me feel anxious and the unknown is daunting.”

“It makes me appreciate the work housing associations do for people, but I’m annoyed at government for ignoring housing as an issue to be dealt with.”

“I feel sad that I have very minimal rights in relation to those we serve – I see the contrast between the rights of social and private tenants to be worlds apart.”

“Of all the people that promote and lobby for more social housing, few live in it and are often homeowners despite being disparaging about those who aspire to have this choice.”

“I have moved to cheaper accommodation (sharing with seven people) in order to reduce costs.”

“I am always looking at things from a customer’s point of view and find myself empathising with their financial struggles. It can be difficult to then turn these emotions off and think of the needs of the business first and pursue arrears when tenants are struggling, often through no fault of their own.”

“I feel unable to complain about occasional poor service as my landlord is my employer.”

“I am a grown adult living with parents.”

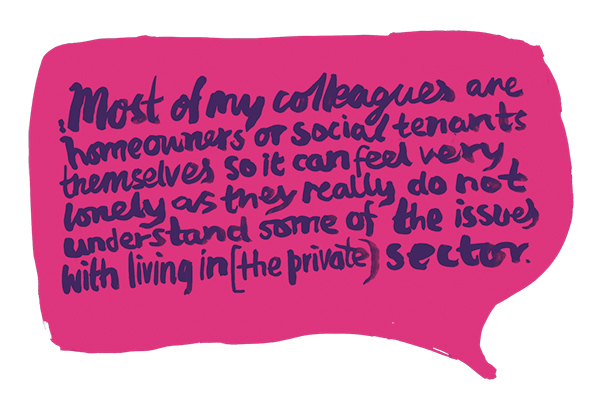

“Most of my colleagues are homeowners of social tenants themselves so it can feel very lonely as they really do not understand some of the issues with living in [the private] sector.”

“Very frustrated sometimes. I am helping people all the time but there is no help for me and my situation.”

“I live on a mixed-tenure estate and think that’s an incredibly positive experience for my family.”

“My housing association is rubbish and penny-pinching when it comes to repairs. They are also quite arrogant.”

“My relationship is fine but I couldn’t afford to stay on if we separated.”

“Other people are in a much worse situation, and without housing associations would end up homeless. I am frustrated that my own housing situation isn’t better, but I think this is the result of government housing policy.”