How social landlords are failing to prepare emergency evacuation plans for disabled residents

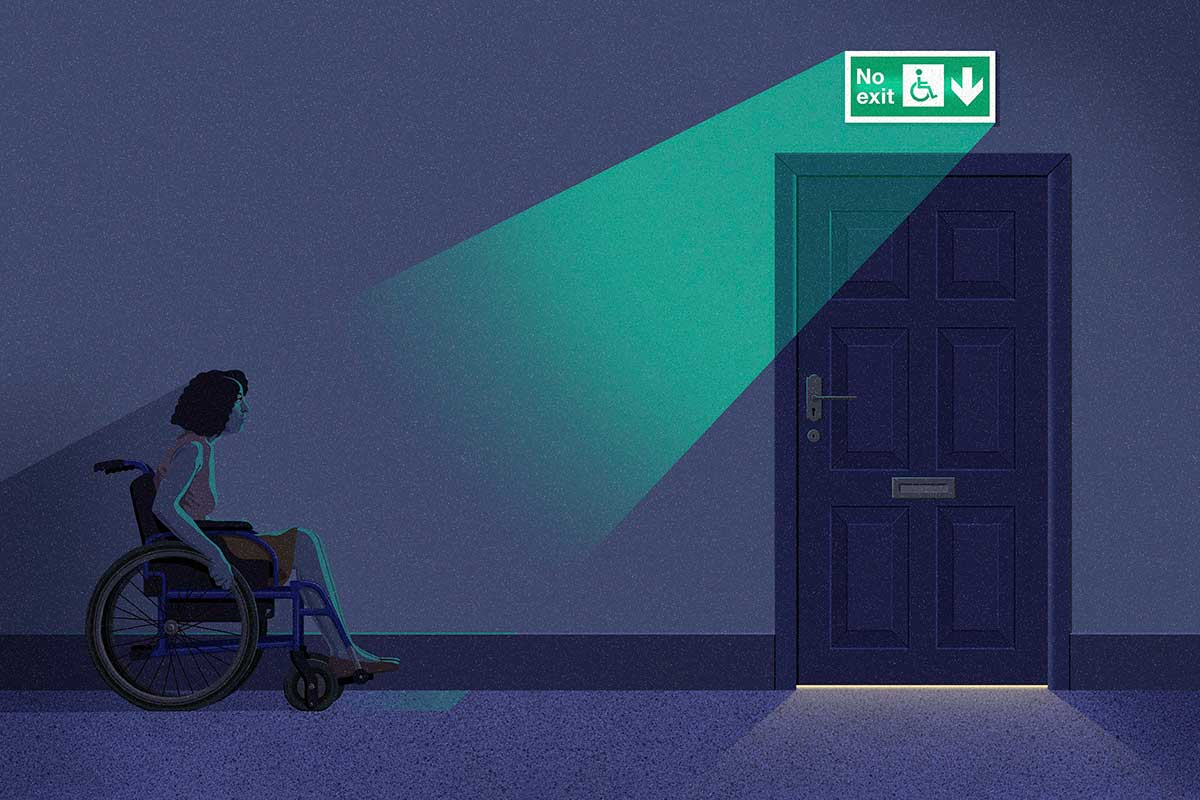

Almost two years after the Grenfell Inquiry recommended personal emergency evacuation plans (PEEPs) for disabled residents in high rises, most councils still do not provide them. Peter Apps looks at what should be done. Illustration by Pete Reynolds

What would you do if a fire started in a block of flats you were in? Stick to the ‘stay put’ advice or get out? How about if it was on your floor and you could see the landing starting to fill up with smoke? Or if your own kitchen was on fire?

Now imagine being in that position but unable to leave. This has been the default position for thousands of disabled people around the country for decades. Despite a legal requirement for all residents to be able to exit a building in an emergency, for many disabled flat occupants, nothing has been done to ensure this is met.

All this might be about to change. The housing sector’s previous total reliance on stay put advice – to stay in your flat in the case of a fire, unless it affects your home or you are told to leave by the fire service – was deeply shaken by the Grenfell Tower fire, which threw the plight of disabled people into particularly sharp relief.

Among the 72 victims of the Grenfell tragedy, 15 were disabled. They died at a higher rate than any other group of people present in the tower. The first phase of the inquiry subsequently recommended the adoption of personal emergency evacuation plans (PEEPs) for all disabled residents of high-rise buildings.

“It’s a scandal really that disabled people are being left without protection. The inquiry recommendations were made in October 2019. What made them think that they still didn’t need to do anything?”

The government was initially reluctant to implement this, after a group of industry lobbyists called it “totally impracticable”. But it relented following legal pressure from bereaved relatives of Sakina Afrasehabi, a disabled woman killed in the Grenfell Tower fire.

It launched a consultation on the issue, which closed over the summer, and new statutory guidelines are expected in October. Ahead of this, Inside Housing looks at what the sector is already doing and what should be done to deliver this complex but crucial policy.

We sent Freedom of Information Act requests to all of England’s stock-owning councils to ask how many purpose-built blocks of flats they owned; how many residents had disabilities which would mean they struggled to escape; how many PEEPs they had prepared; and what their policy was on doing so.

The results show that most local authorities still do not make PEEPs for residents who need them. Of the 67 to respond – owning close to 40,000 blocks of all heights – two-thirds (42) did not provide PEEPs in general needs housing. Of these, 25 did not provide them in specialist housing either.

“We strongly believe that there needs to be a common approach to introducing PEEPs across London. We would like to see a system whereby residents alert us if they require evacuation assistance”

These include large London boroughs with thousands of buildings, such as Westminster, Camden and Greenwich, as well as some large councils from around the country such as Stoke, Norwich and Portsmouth.

Is this a surprise? It is certainly indicative of common practice before Grenfell (supported by government-endorsed guidance which called evacuation plans for disabled residents “usually unnecessary”). But it is also almost two years since the Grenfell Tower Inquiry recommended the adoption of PEEPs.

Fazilet Hadi, head of policy at Disability Rights UK, calls the figures “shocking”. She says: “It’s a scandal really that disabled people are being left without protection. Even if you think that the guidance misled [social landlords], the inquiry recommendations were made in October 2019. What made them think that they still didn’t need to do anything?”

Capital problem

Camden, which has the largest number of blocks of any council in our survey not to have a policy for PEEPs, says it believes a consistent approach is needed across London and that the borough is considering its approach at director level.

“We are working closely with the London Fire Brigade, London Councils and the [Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities] to address the practical challenges housing authorities will face when putting these in place,” says Meric Apak, cabinet member for better homes.

“We strongly believe that there needs to be a common approach to introducing PEEPs across London. We would like to see a system whereby residents alert us if they require evacuation assistance. We would work with residents to ensure this information is kept up to date and amended if their circumstances change.”

“The idea that our employees can manage an evacuation in a live incident is false. So the important thing for me is that the fire service has got access to that information and can act on it”

Even where policies are in place, many produced fairly few plans. Redbridge Council, for example, responded to say it makes referrals to the London Fire Brigade and completes PEEPs in conjunction with the authority. But it had just one plan in place across 5,200 flats in its stock.

In total, the local authorities were able to identify just 4,042 PEEPs across the 40,000 blocks of flats. These will likely hold well over half a million residents.

What about the councils that are producing PEEPs? Bob Porter is director of housing and planning at Thanet Council in Kent, which has 61 PEEPs in place across six high rises. The authority updates them when a new tenant signs up and checks them on a monthly basis.

“The plans are developed in conjunction with the fire service,” he says. “We keep copies of the plans on the ground floor. In the event of a live incident, the fire service can see straight away who is in need of rescue.”

The PEEPs Thanet Council has produced rest on the idea that if the block requires evacuation, it is the fire service which will carry out the rescue. This means the issue of not having staff present is irrelevant, which was one of the objections the sector raised to say that PEEPs are impractical.

“In a live incident, the only people that really are confident and equipped and trained to go into a building are the fire service,” Mr Porter explains. “The idea that our employees can manage an evacuation in a live incident is false. So the important thing for me is that the fire service has got access to that information and can act on it.”

“If the flat of the disabled person is on fire or the one next door is, they have to be able to move away from the fire. And if they have a problem moving vertically, they can’t. After 20 minutes in the near vicinity of a fire, the chance of a fatality is extremely high”

He says the major challenge has been identifying residents who need help. “Being clear about who leads on that is crucial,” he says. “You’ve got to have the resources in place to do that upfront.”

It is a similar story in South Tyneside, where the authority has developed 220 PEEPs. Paul Mains, managing director at its ALMO South Tyneside Homes, explains: “[After Grenfell] we did an assessment of every single person and talked to them about how quickly they could evacuate. For us it was [about asking], ‘Can you get out and can you get out safely?’”

Its arrangement with the local fire service means that information on any disabled residents will be deployed electronically to crews en route to an incident. “They know when they arrive that Mrs Smith in Flat 7 needs to be evacuated,” explains Mr Mains. “But they know what the issues are as well. They know exactly what they need to do to evacuate the building, if it becomes necessary.”

Collecting this information is a crucial step, and the councils are acting on the advice of the fire brigade. But reliance on the fire service for rescue is not a PEEP. Guidance – for example British Standard 9991 – is clear that residents must be able to evacuate without the assistance of firefighters for compliance with legal duties.

“The law is black and white: everyone needs to be able to leave the building,” says Elspeth Grant, a PEEPs expert and trainer at Triple A Consult. “When you consider it will be 28 or 29 minutes before the firefighters will be in position, you cannot have sole reliance on firefighters.

“If the flat of the disabled person is on fire or the one next door is, they have to be able to move away from the fire. And if they have a problem moving vertically, they can’t. After 20 minutes in the near vicinity of a fire, the chance of a fatality is extremely high.”

In numbers

15

Victims of Grenfell who were disabled

42

Councils surveyed which did not have PEEPs

2019

When the Grenfell Inquiry recommended PEEPs

Help from friends

How to solve this problem, then? For Ms Grant, the answer is those already in the building: family, friends, carers and neighbours.

“There is nothing in the law which says the person assisting with the evacuation has to be an employee. They just have to be competent and trained,” she says. “Family, friends and neighbours support disabled people all the time, and they are not going to leave them in an emergency situation.”

“We got an evacuation chair for me and training for my personal assistants so they can use it. But I’m one of the only disabled people who actually has a PEEP – everyone else is being flatly refused one”

This is a fact that was borne out by the Grenfell Tower fire. A number of victims were relatives who stayed behind, unable to leave their loved ones.

There are also PEEPs that will not require a buddy. For deaf residents, it may be a case of vibrating alarms, for those with arthritis, it may be about low-pressure door handles, for those with learning difficulties, it may be voice-recorded alarms and regular practice.

But where buddies are required, it is likely that an informal system is already in place. “If you are severely disabled, you have to have support to live in a tower block,” says Ms Grant. “My view is that this is about reducing the risk as much as you can, but there is no such thing as risk-free.”

“A good plan is short, understandable and proportionate,” says Ms Hadi. “It’s fully understood and agreed to by the disabled resident. It’s a recorded conversation about some proportionate measures in the event of a fire to leave the building.”

Sarah is a wheelchair user in a block with dangerous cladding in Birmingham. She is also a founding member of Claddag, a support group for disabled residents of high rises known to have fire safety issues. She believes she is one of the only residents of such buildings to have a PEEP. “We got an evacuation chair for me and training for my personal assistants so they can use it. But I’m one of the only disabled people who actually has a PEEP – everyone else is being flatly refused one,” Sarah says.

“The position for the past couple of decades was totally out of step and irresponsible and, frankly, ableist”

Along with Ms Hadi, Sarah has contributed to working groups on the government’s new approach, but she has some major concerns. First, she is worried that this will only kick in for buildings taller than 18 metres.

“You could be a wheelchair user on the second floor of a 20-storey building and get a PEEP, but a wheelchair user on the fifth floor of a six-storey building [would] not be entitled to one,” she explains.

Sarah has concerns that ‘self-identification’ may result in landlords not being proactive enough. “We don’t like the idea of the trigger being self-identification because if you don’t know how things work, you’re not going to raise it. Landlords should be contacting residents to ask if they would struggle to escape the building,” she says.

She also worries that the consultation was silent on cost. Not all PEEPs cost money, but some do – and the question of who will pay for them has been left hanging.

Overall, the sector is going to have to get to grips with an issue that some have been reluctant to tackle. “Some of the comments made in the workshops suggested social landlords were resistant to change. It felt like there was quite a big chasm between where they were and where some disabled people were,” says Ms Hadi.

“The position for the past couple of decades was totally out of step and irresponsible and, frankly, ableist,” says Sarah. “It is time for change.”

Sign up for our fire safety newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters