You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

How Birmingham became the centre of a supported housing controversy

Exempt accommodation houses some of the most vulnerable people in society, but a lack of regulation means many are being forced to live in horrendous conditions. Jack Simpson investigates

Content warning: the following piece contains references to sexual assault, rape and murder, which readers may find distressing

“Look, there it is, that’s the blood-soaked carpet,” says Joey (not his real name), as he scrolls through images on his phone of the place he has called home for the past eight months.

“They stabbed him a few times and there was enough spray to reach that wall,” he explains, recounting the night a housemate entered his room with stab wounds from another tenant.

He scrolls down to a photo of doors with machete marks, the remnants of a rampage by a housemate and his friends.

The next one shows the full contents of Joey’s room dumped in the back garden. This was the night he was unceremoniously evicted from his previous property by his support worker.

“We’ve had fungi growing through the floors because of the damp, our washing machine didn’t get replaced for months, and we’ve had maggots and flies,” he tells me, pointing out an image of large mushroom-like organisms growing out of a door frame.

The images are shocking, but for people like Joey who live in non-commissioned exempt accommodation (EA), they are becoming all too familiar.

EA is supposed to provide homes for those hardest to house, such as domestic abuse survivors, recovering addicts and refugees. It should be a safe haven, giving support to help these people make the next step in their lives. And often it is.

However, in an increasing number of cases, providers are benefiting from the high housing benefit for which these homes are eligible, but are not providing what is needed.

The result is tenants being forced to live in horrendous conditions, while the government pumps millions into these properties, with a lack of oversight or regulation of whether it is being used correctly.

Nowhere is EA more abundant than in Birmingham.

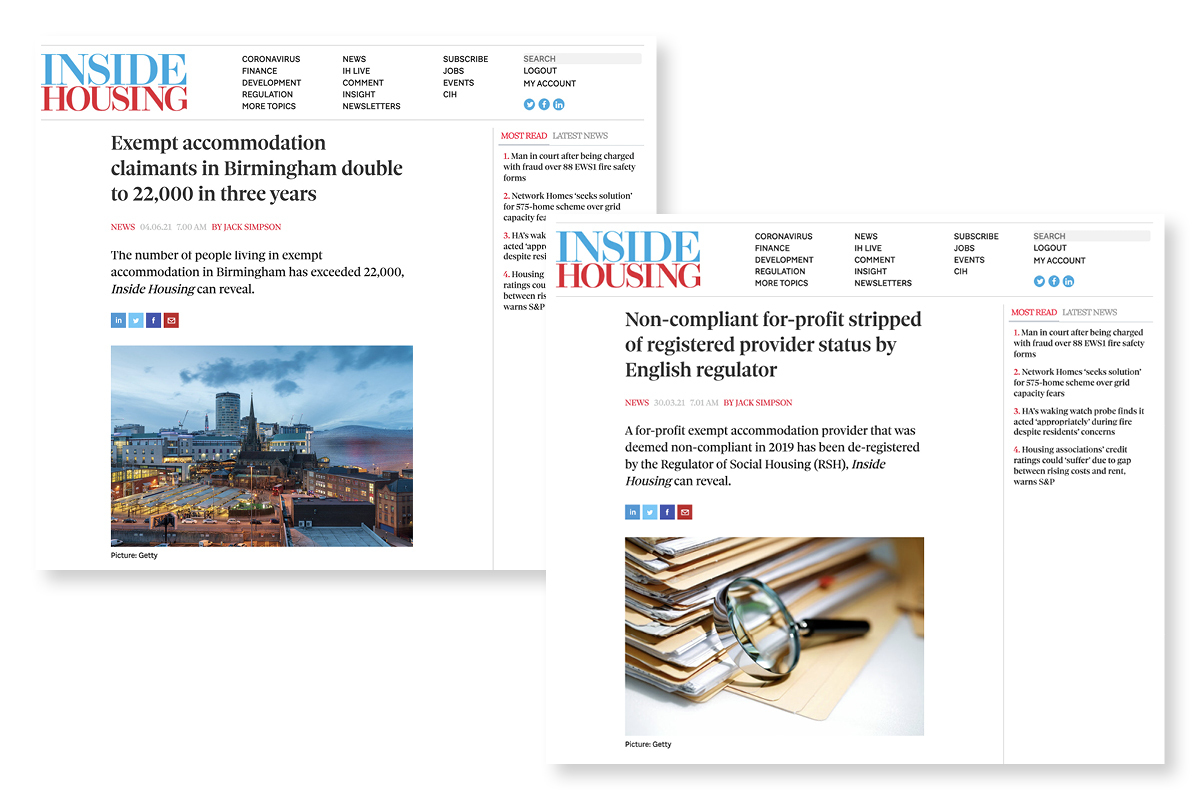

Over the past eight years, the numbers in the city have ballooned seven-fold to more than 21,000 claimants.

With this has come an influx of problematic EA properties that are causing misery for those living in them.

The growth of EA

EA is a form of supported housing not widely known about or understood.

Provided by housing associations, often through managing agents, charities or community interest companies (CICs), it is offered to people with few other housing options, such as migrants, those fleeing domestic abuse, prison leavers and recovering addicts.

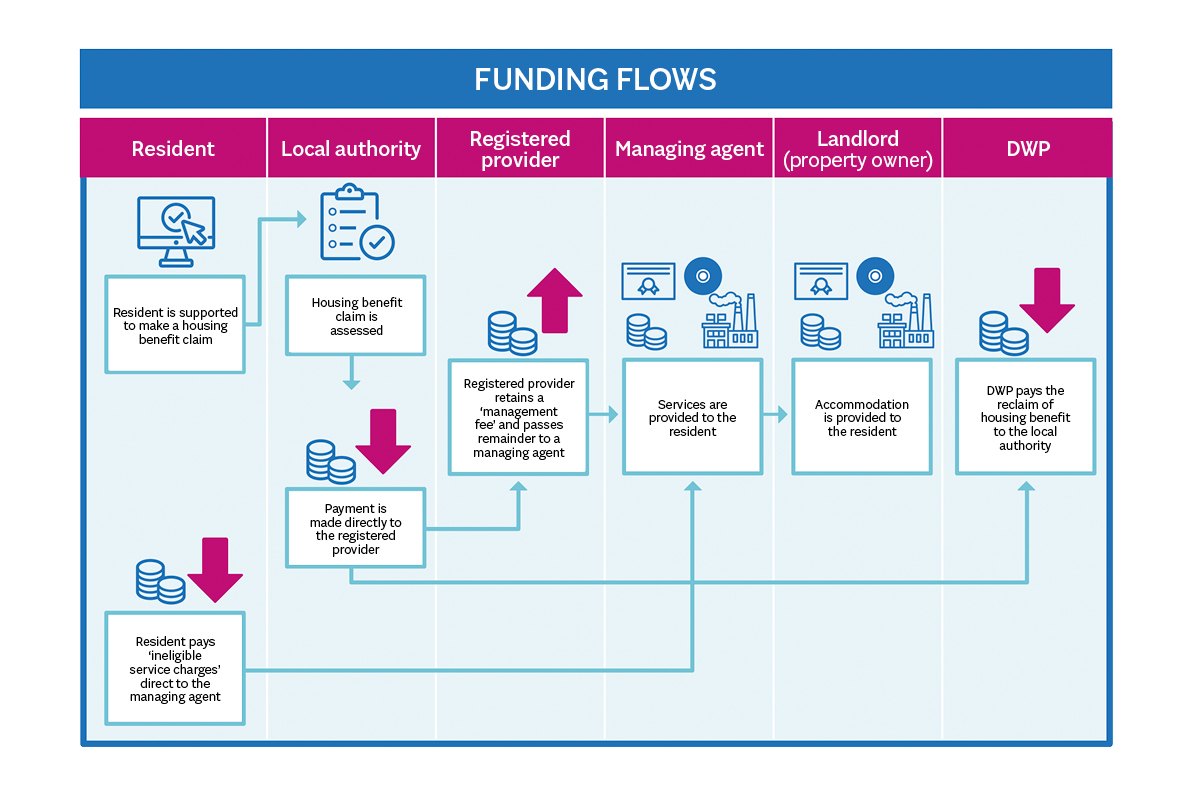

If a provider gives a small element of care, support and supervision, it is ‘exempt’ from usual rules which limit the amount of housing benefit tenants can claim to Local Housing Allowance rates.

The additional rent is supposed to cover the ‘intensive housing management’ that needs to be provided by landlords. And providers often demand an additional ‘service charge’ to cover the support.

This means payments are usually extremely high.

In Birmingham, the maximum amount of housing benefit that can be awarded for someone living in a shared room in a traditional house of multiple occupancy (HMO) is just over £291 a month.

In exempt accommodation, it is over £850. An extra £60 in service charge can also be taken.

While in many cases this is justified due to the additional costs of managing these properties, in some, the care or intensive management is non-existent.

“People came to Birmingham because housing benefit was easy. If you go to neighbouring councils, like say Walsall and Dudley, you can’t get anywhere near the rates that you can in Birmingham.”

Instead, some providers secure the high rents, invest little in the homes or support, and cream off the huge margins.

This is possible because of ambiguity around the definition of how much care must be provided, legally set as “more than minimal” or “trifling”.

Some supported housing is commissioned by councils, giving them more oversight of providers and conditions. However, Birmingham, like many other councils, has seen its commissioning budget slashed since changes to the government’s Supporting People fund for supported housing.

It has now halved to around £24m for commissioned services, whereas when Supporting People was ringfenced, it was over £50m.

This has led to it becoming reliant on non-commissioned EA, which does not have council oversight.

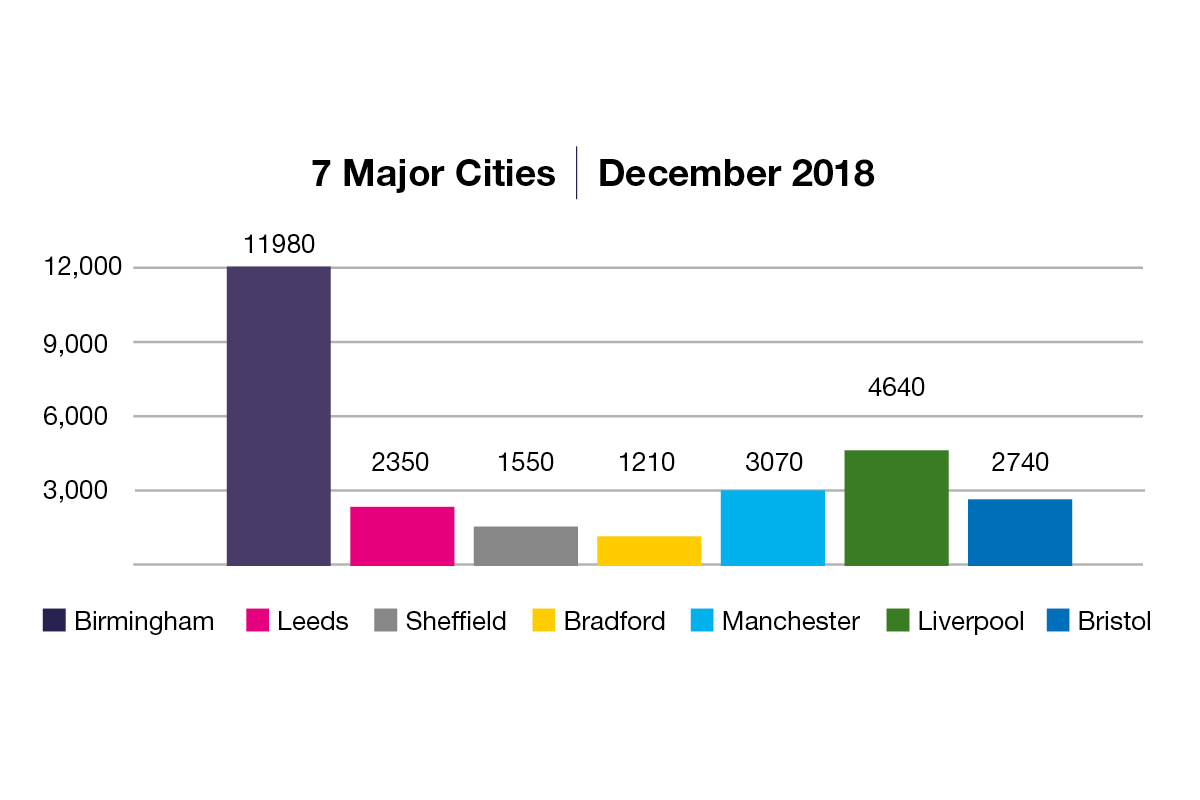

Go back to 2014 and Birmingham, with only 3,679 EA claimants, had a similar amount to other UK cities. But by 2018, exempt claimants had hit 11,980, nearly treble those in Manchester, and quadruple those in Leeds.

There are now more than 21,000 claimants in Birmingham, 15% of all the 150,000 UK claimants. Birmingham houses 6% of the UK population.

And the vast majority of these homes, and the providers that supply them, provide desperately needed accommodation with essential support.

Birmingham has provided fertile conditions for this growth. The city has its own constant demand for housing, with a housing waiting list of 17,000 households – including its large Victorian properties, which are ripe for conversion into HMOs, the ideal type of housing for EA. But it is the council’s housing benefit regime that has really fuelled this growth.

“People came to Birmingham because housing benefit was easy,” says one person in the exempt sector who has worked for managing agents and housing associations. “If you go to neighbouring councils, like say Walsall and Dudley, you can’t get anywhere near the rates that you can in Birmingham.”

Birmingham says that it applied the benefit rules strictly to government legislation and that it has an extremely robust application process.

It told Inside Housing that the Department for Work and Pensions reviewed its processes and said it had “extremely good practice.”

But our anonymous source adds that in neighbouring councils, it is more difficult to get EA claims through, with longer wait times and more chance of being rejected.

Some working in the housing sector in Birmingham have said they feel that the council applies the housing benefit regulations fairly but is hampered by the lack of detail in the definition of care and support.

This, they argue, means that Birmingham does not have a choice legally but to accept claims.

And as Birmingham’s housing benefit reputation as a good place to provide EA grew, so did the number of exempt properties.

EA providers are not only housing homeless people from the West Midlands, but also the rest of the UK. Recent assessments by the council found that of the over 21,000 current claimants, fewer than 9,000 units were needed for local groups of vulnerable people, with a large proportion coming from outside the city.

When Inside Housing visited Birmingham, we spoke to people from as far afield as Winchester, Cheshire, London and Hereford, who ended up in the city because of the availability of exempt housing.

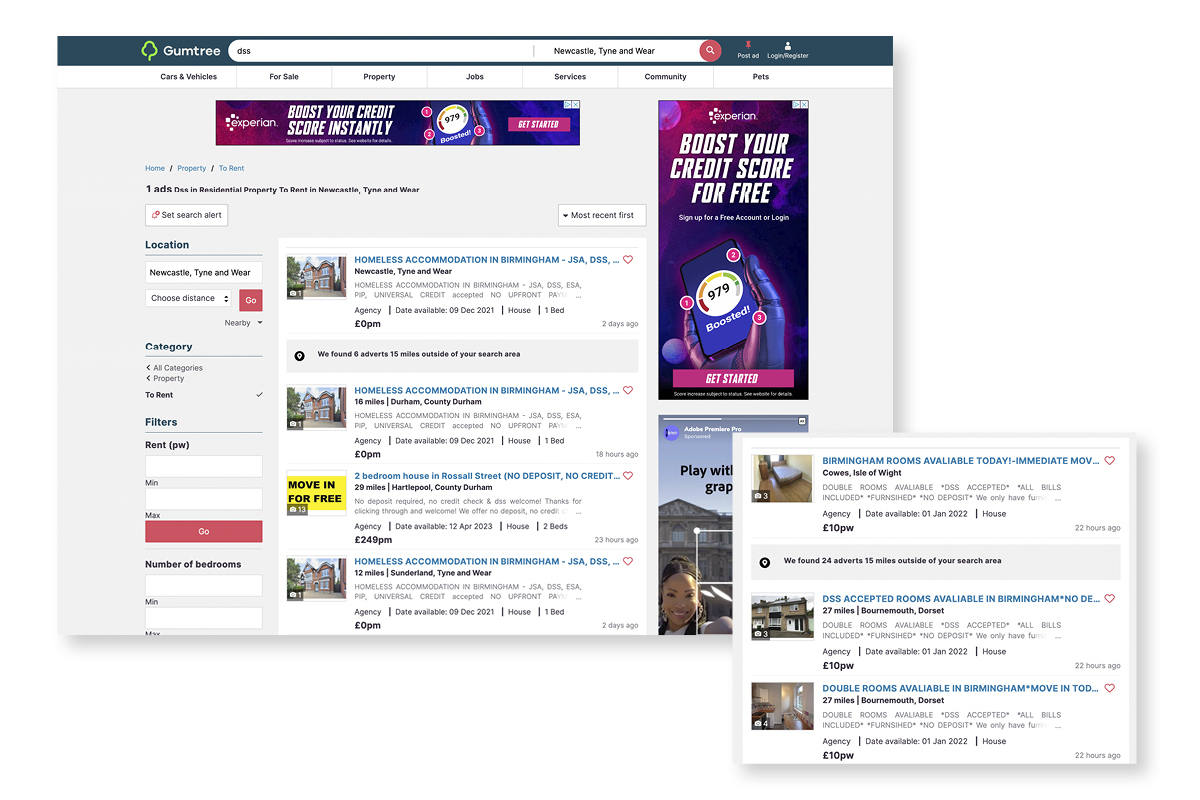

Some have self-referred, attracted by adverts posted by Birmingham landlords on local Gumtree pages, which promise cheap or non-existent rents, and call for those on benefits to get in touch.

Meanwhile, councils in other parts of England are sending people to Birmingham. Inside Housing has heard of exempt providers forming close links with councils or other referral agencies and even employing drivers to pick up tenants from the train station.

Dominic Bradley, chief executive of housing provider Spring Housing, explains: “At an operational level, we know that people presenting to other councils are, overtly sometimes, but also less explicitly, being directed to providers in Birmingham.”

Many prison leavers are being advised to travel to Birmingham because of the housing situation.

“What is the hardest thing for prison resettlement teams? It’s housing. If you have got providers saying we will take whoever you have, they jump at that,” explains Mr Bradley.

But demand needs to be matched by supply. So, who are the providers driving the growth?

To understand which organisations have driven the exempt accommodation boom, it is worth looking at the biggest providers in March 2021, when the biggest boom happened.

Of the 22,000 claimants recorded at the time, 73% were being housed by just seven providers.

There are two things they all shared. One, they operate a lease-based model and often use managing agents to deliver housing and support.

Two, they all have been deemed non-compliant by the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH).

The lease-based model, which was adopted by Birmingham’s big providers, has become synonymous with the city, with 93% of provision coming through this model.

The housing association is the head landlord, has a licence agreement with the tenant and has the Universal Credit paid directly to it.

It will then hold dozens, in some cases hundreds, of lease and management agreements with a network of managing agents that provide the housing and support.

The association retains a management fee, often around 13%, but then transfers the majority of the payment to a managing agent. The sums involved in Birmingham are huge. Birmingham City Council told the The Independent and Open Democracy that it had paid £555m, including some to general needs housing, to 18 exempt providers since 2018. There have been no complaints against these providers and we have no reason to believe that the accommodation they provide is in any way unacceptable.

EA can also be provided directly by a managing agent. However, the managing agents would often have to go through certain planning laws that associations do not, and some of the funding comes from the council’s budgets when an association is not involved, making it more difficult to get claims accepted in some cases.

The properties are either bought by the registered provider or managing agent, or leased from individual landlords. These landlords are offered guaranteed rent, with no management responsibilities in some cases, under four-year lease agreements.

But the RSH has been able to use its powers over providers’ governance to criticise the lease-based model used by all of Birmingham’s biggest exempt providers, which sees them effectively sub-contract care and support of vulnerable tenants to managing agents, which they have no power to regulate or intervene on.

Prospect was given a G4 rating, the lowest rating for governance, after reviews by the RSH discovered weaknesses in controls over services provided by third-party managing agents in relation to two safeguarding events, including the murder of a tenant.

But the RSH also has concerns about how the managing agent model can be used as a way of filtering money to linked companies.

In several cases, it raised concerns that providers had failed to ensure, or in some cases demonstrate, that arrangements “do not inappropriately advance the interest of third parties”.

In 2019, the RSH raised concerns over conflicts of interest at exempt provider Sustain, where it was later revealed that £1.3m had been paid to companies that were linked to directors. Sustain said that the directors in question left the business last year, all conflicts are now resolved and as of September 2021, it was compliant with all areas other than the Rent Standard.

Similar concerns were raised about New Roots. A “forensic audit” commissioned by new management would later discover a series of payments to companies owned by members of New Roots’ senior staff or family members.

This would include the former chief executive using company funds to buy a motorhome off a previous spouse.

Prospect has now closed down after a new management team took over, while new leadership at New Roots withdrew from the sector and voluntarily de-registered as a housing association.

The new management of New Roots had the most stinging assessment of the model, with its chair Andy Howell labelling the lease-based model “intrinsically unsafe”.

Another large provider, Green Park, was also forced to close after having its exempt accommodation status stripped by Birmingham City Council.

But the exit of three major players has not led to a drop in exempt numbers.

This is because once a provider shuts down, the managing agents, more often than not, just move under another provider. This has concentrated the stock between fewer providers.

Now 13,565 claimants, 64% of the 21,179 claimants, are housed by just three providers: Ash Shahada, Concept and Reliance.

All three providers started life outside of Birmingham, but moved to the city ahead of the exempt boom.

There is no suggestion of malpractice against the specific providers above and we have no reason to believe the accommodation they provide is unacceptable.

Concept said that providing the best support to residents is its priority and that its board decided to suspend plans for further growth until it was assured that any future growth could be managed appropriately. Ash Shahada has been contacted.

The biggest is Reliance Social Housing CIC, which is the lead provider for 8,034 claimants, more than a third of all bedspaces.

This is remarkable growth for an organisation that was a dormant association based in Gravesend, Kent, just a few years ago, and only secured its first supported housing scheme in August 2018.

An investigation by The Independent and Open Democracy found that it had been paid £161m in housing benefit in the past four years.

As it has grown, it has not escaped the gaze of the regulator and local politicians. In October 2021, it was deemed non-compliant with the RSH’s Governance and Financial Viability Standard, with the RSH saying it had not been able to demonstrate that it is managing its affairs with an appropriate degree of skill, independence, diligence, effectiveness, prudence and foresight.

“I’ve felt like a complete prisoner in my own house at times”

Last month, Sharon Thompson, Birmingham’s cabinet head of housing and a councillor in North Edgbaston, wrote to Reliance raising concerns about the conditions of some of its properties, saying she had seen photographic evidence showing some “shocking living conditions, as well as a lack of support”.

Reliance told Inside Housing that it was working with the council and the regulator to ensure the quality of service and support is meeting the required standards, and that it had implemented a robust action plan to ensure it is fulfilling strategic objectives and regulatory compliance.

It also criticised Ms Thompson’s decision to publish her letter without contacting Reliance, and added that as an organisation, it will continue to prioritise the welfare of tenants, and regularly review and seek to enhance its complaints procedures.

Many EA properties are good quality, providing essential support and a roof over the heads of thousands of people who would not otherwise have this.

“There are a lot of really good providers across the city, where they absolutely provide good levels of support,” says Preet Gill, MP for Edgbaston.

However, Ms Gill, who last year carried out a series of unannounced visits to exempt hostels in her constituency, says she believes that in too many cases, providers are not doing this and conditions are sub-standard.

Inside Housing has spoken to a number of exempt accommodation residents who have described some of the situations they have had to endure.

These ranged from damp problems and pest infestations, to space issues, with landlords putting up partition walls in already small bedrooms to squeeze in additional bedrooms.

Another consistent complaint was not being provided with basic amenities.

This includes tenants who had gone months without internet, electricity and gas, even in the colder winter months.

Inside Housing spoke to one resident who suffers from a condition that affects his mobility and sometimes has to use a walking stick or a wheelchair. He has lived in three exempt properties, none of which have been adapted to help him. In the current one, his bedroom is at the top of a flight of stairs. “I’ve felt like a complete prisoner in my own house at times,” he says.

There are also significant repairs issues on many properties.

In one case Inside Housing was told about, a broken waste pipe left human waste collecting in a back garden during the recent heatwave.

Despite complaints to the landlord, it took over a month to fix, with the pool growing every time a toilet was flushed.

Out of 431 property inspections carried out by Birmingham between November 2020 and September 2021, it found 1,120 Category One hazards in EA properties. These are hazards that pose a “serious and immediate” risk to a person’s health and safety.

And many residents are afraid to complain, with landlords often threatening them with 24-hour evictions if they do. Joey spoke of one incident he had seen where a new tenant was evicted after only a couple of days, just because they raised concerns about the key situation.

“Residents are generally terrified because they know that they’re on excluded licence agreements. If they say something bad about the managing agent, they know that they could be booted out,” says one person who has worked in exempt accommodation.

To access the higher level of housing benefit, providers must supply more than minimal care for tenants, but there are questions about whether this is being provided in some cases.

Inside Housing spoke to several exempt claimants whose care consisted only of a support worker coming around once a week, getting them to sign a support plan and then leaving.

“They are supposed to spend an hour with you, help you with prescriptions, take you to appointments and stuff, but you don’t get that support,” says Princess Morton-Wade, who has lived in six Birmingham EA properties. She says: “Standards of care don’t exist. As long as you have a National Insurance number and can claim, that’s what they care about.”

‘Shocking cases’

This stretches to duty of care, too.

EA in Birmingham has become a magnet for what are called ‘risky mixes’. Speaking in parliament in February, Jess Phillips, MP for Yardley, told the story of a constituent who was a young victim of rape but had been placed in EA as the only woman in a property exclusively filled with men, including convicted offenders and abusers.

Ms Morton-Wade says she has seen the effects first-hand, recounting a story where a woman was so scared to leave her room that she would use her bin as a toilet.

“She had Crohn’s disease, it was awful,” she explains. “A guy was trying to get into her room and the support workers didn’t step in. We had to manhandle him out of the house.”

Case studies supplied to a select committee investigation into exempt accommodation by the police outlined incidents where a female resident was sexually assaulted by a staff member, while in another case, a tenant was raped by a landlord under threat of eviction.

The Domestic Abuse Commissioner’s submission to the select committee highlighted a number of “shocking cases” in recent years, which have seen “potentially preventable homicides take place in exempt accommodation”.

This includes the murder of Phoenix Netts, who was killed by Gareeca Gordon – her housemate in a Birmingham exempt property – after she turned down Ms Gordon’s sexual advances.

Ms Netts’ body was found in Gloucester dismembered, burned and packed into a suitcase.

EA is growing outside of Birmingham, too.

Research by homelessness charity Crisis showed that numbers in EA had grown by 62% in Great Britain, from 95,149 claimants in May 2016, to 153,701 in May 2021.

Reflecting on the statistics at the time, Jon Sparkes, then chief executive at Crisis, called the sector “dangerously unregulated” and said “stronger regulation is needed to keep the wrong people out”.

And this is where the issue of exempt accommodation lies.

Despite housing more than 21,000 claimants in Birmingham, and 150,000 across the country, there is very little regulatory oversight. For those providers that the RSH does regulate, currently it can only assess them on their governance and financial performance.

At the moment, it cannot inspect housing conditions and take action unless there is a threat to health and safety.

The regulator is also further hamstrung by the fact that most of the housing and care is provided by managing agents, which it has no power to regulate. In many cases, landlords and staff within EA do not even need a criminal record check to operate as a managing agent.

Outside of Birmingham’s managing agents, CICs and charities provide the care and housing, sometimes under the remit of the Care Quality Commission or the Charity Commission.

Jonathan Walters, deputy chief executive of the RSH, says: “The recent select committee investigation has highlighted that no one body could say that they regulate all of the exempt accommodation providers. It was clear they consider that to be an issue.”

This has led to calls for local authorities to be given more powers. A letter sent earlier this year by the Local Government Association, and signed by 41 other organisations, called for local authorities to be empowered to assess the need for housing-related support and develop a new ‘exempt accommodation strategy’ so councils can be actively engaged in oversight of this sector.

Stemming the rise

In the past two years, Birmingham has managed to stem the rise in claimants, with numbers largely plateauing around the 21,000 mark. Inside Housing understands this is partly down to a more challenging environment for providers to get through housing benefit claims.

Nationally, there seems to be more meaningful action to gain control of EA. This pressure has forced the government to listen. Last year, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities set up an inquiry into EA and is set to publish a report next month.

In March, rough sleeping and housing minister Eddie Hughes announced that the government was launching a crackdown on unscrupulous exempt accommodation with a raft of proposals.

These included new powers for local authorities to manage their local supported housing market; changes to the housing benefit system to better define care, support and supervision; and the introduction of minimum standards for tenants.

“They say, ‘But you’ve got a roof over your head.’ Yeah, but what if that roof leaks, your housemates are scary, I mean really scary, and you have rodents crawling all over the place?”

The Social Housing Regulation Bill will also give the regulator more powers to intervene when it comes across poor housing conditions or repairs issues.

But it is important to point out that these will be powers only for social housing, and not necessarily for exempt accommodation.

Legislation within that bill will also include new ‘look-through’ powers for the regulator that would allow it to investigate money paid to managing agents.

But there is a tricky balance that new regulation and legislation needs to strike.

Any regulation could see a mass pull-out of the market, and this could result in the good providers withdrawing because it is not financially viable, and cause a major homelessness problem.

“That is the reason there is a lot of trepidation about when and how to change the sector, because if they disrupt the market too much, they are going to end up with a lot of people on the streets,” explains Thea Raisbeck, author of Exempt from Responsibility, a report looking into Birmingham’s EA.

This is something Birmingham City Council is all too aware of. “It is definitely a fear, and we recognised that early on because we had a couple of large providers that came out of the sector in Birmingham,” explains Guy Chaundy, the council’s senior manager for housing strategy.

He says that the council does not want to “kick people out of the sector” and that instead it has drawn up a five-year exempt strategy to “manage exempt provision down” over time.

But for those living in poor exempt conditions, having accommodation is one thing, but it can be detrimental if the conditions are awful.

“They say, ‘But you’ve got a roof over your head.’ Yeah, but what if that roof leaks, your housemates are scary, I mean really scary, and you have rodents crawling all over the place?” says Ms Morton-Wade.

She believes there needs to be more focused action on improving standards.

The government appears to agree. Speaking in the final session of the select committee’s investigation into exempt accommodation, Mr Hughes said the government “completely accepted” that there is a problem with EA and vowed that it would “do its damnedest to make sure it is addressed”.

But while the words will be warmly received by Ms Morton-Wade, Joey and the thousands of other exempt tenants in Birmingham and across the country, it is action that they need to see now – action to ensure that this type of housing, which can be such an important part of the supported housing mix, does what it is meant to do, and the exploitation of the system and those living in it stops.

If you live in or have been affected by exempt accommodation in Birmingham or elsewhere, please get in touch with me at jack.simpson@insidehousing.co.uk

Sign up for our care and support newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters