You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

How bereaved families are being stung by the costs of shared ownership

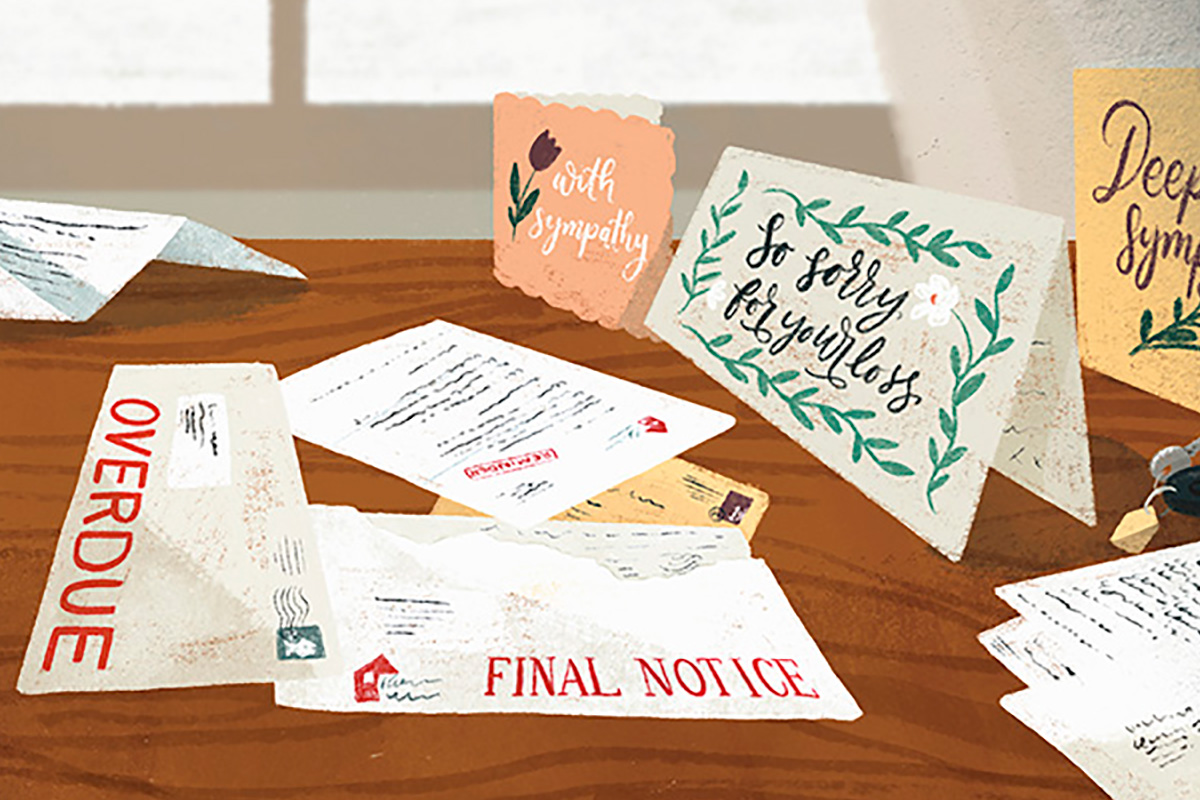

Housing associations are building more and more shared ownership homes. But if the owner dies, families may be left to foot the bill. Nathaniel Barker reports. Illustration by Becky Thorns

Death, unfortunately, has never been far from the headlines in recent months. Since mid-March, more than 42,000 people have died in the UK from COVID-19. At one point in April, the Office for National Statistics was reporting the highest weekly number of fatalities since records began 20 years ago.

Around the time of the outbreak, Penny Ashcroft contacted Inside Housing in distress. She was being pursued by housing association A2Dominion for £25,000 in unpaid rent on her deceased mother’s shared ownership flat.

The flat passed to her as executor of the estate after her mother, Lois Plowman, died in January 2018. Despite Ms Ashcroft’s best efforts, she was unable to sell it. Her requests for A2Dominion to buy back the equity share or allow her to sublet the flat came to nothing, leaving the arrears to pile up.

"I wouldn’t be able say, ‘I think this is the way organisations should do it.’ I think they should look at it case by case and find solutions for each person. You are having to navigate quite a complex legal scenario and the best way to do that is to use an approach agreed on a case-by-case basis”

A2Dominion has since apologised and granted Ms Ashcroft a £12,500 discount on the arrears. She was eventually able to sell the flat in April, paying back about £17,000 of the money raised to A2Dominion to clear the debt.

But the incident raises the question of just how common Ms Ashcroft’s experience is. The timing makes that question all the more pressing: COVID-19 continues to take its toll and shared ownership is becoming increasingly mainstream, so the case is unlikely to be an exception.

Inside Housing has investigated what happens when social housing residents – particularly shared owners – pass away and what landlords should consider when handling this most sensitive of scenarios.

Where rented homes are concerned, the situation is generally straightforward and the tenancy can simply be ended after a notice period. Tenancy succession rights are well-established, mostly through the Localism Act 2011 and the Housing and Planning Act 2016, as well as extensive case law on disputes that may arise.

“When one of our tenants passes away, we’ll usually get notified by the person dealing with the account,” explains Tim Millns, director of income and leasehold services at 57,000-home Metropolitan Thames Valley Housing (MTVH). “We’d expect to see the death certificate, then check that this is the same person involved in the tenancy. In some cases, there will be succession rights depending on the type of tenancy, the law on statutory succession and the contractual terms.

“Remaining at the property will depend on whether the property is fit for the residents staying there – if it’s a three-bed and there’s just a single person there, we would offer them a smaller property based on need.”

For leasehold properties, the inheritor will still need to pay service charges, but subletting or selling the property is relatively uncomplicated.

As Ms Ashcroft’s case demonstrates, it is in shared ownership where problems are likely to emerge. There is no dedicated national guidance on this issue; rent is also due in this tenure, while subletting is generally forbidden; and reselling the property can be more complex, as there are the interests of three parties to consider: the leaseholder, the landlord and the mortgage lender.

Inside Housing asked the UK’s 20 largest housing associations about what they do when a shared ownership leaseholder dies. A2Dominion confirmed in an email to Ms Ashcroft that it “does not have a specific policy with regards to the payment of service charges and specified rent in probate situations” – and based on the responses to our queries, it is not alone. Of the 16 organisations that replied, only five referred to policies, while the rest indicated they take a case-by-case approach.

Sarah Davis, senior policy and practice officer at the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH), says: “There are several very difficult things that could intersect here, including lease agreements or even potential cladding issues. I wouldn’t be able say, ‘I think this is the way organisations should do it.’ I think they should look at it case by case and find solutions for each person. You are having to navigate quite a complex legal scenario and the best way to do that is to use an approach agreed on a case-by-case basis.”

Some interesting points jump out from the responses to our straw poll of housing associations. None indicate that they would not expect the inheritor to take over service charge and rent payments, with a quick resale generally the preferred option.

“Within most housing associations with a lot of shared ownership, there will probably be a resales team and we normally have resale rights,” explains MTVH’s Mr Millns. “Generally, that gives us an opportunity to resell in the first eight weeks, as we essentially take the role of estate agent.”

He says that nine times out of 10, a buyer is found during those eight weeks, which is “the neatest solution”.

But as we saw in Ms Ashcroft’s case, sometimes things are not so neat and debt begins to rack up. Here, the housing associations’ flexibility may be tested.

Some of them have measures to ease the rent and service charge burden where necessary. For example, 43,000-home Orbit says: “No action is taken to recover these costs until the property is sold.” That means someone handling the estate of a loved one will not be hounded for arrears. However, it does not mean Orbit will waive those costs, so arrears could still build up to a large sum, even if they defer payment.

“One of the circumstances in which we allow subletting is where the need to sublet stems from a genuinely unavoidable need and is not primarily for speculation or gain. Cases where a leaseholder has died may fall under this criterion”

A schism emerges among the landlords over the question of buying back property and subletting. Clarion, the 125,000-home association, says its team will offer a range of options, including “support in selling their share of the home back to Clarion, selling to a nominated purchaser or living in the property themselves”. Platform, which has 47,000 homes, also considers buy-backs “where it is possible and feasible to do so”. Wheatley – a separate case, as it is a Scottish landlord with only a small number of shared ownership homes – operates a similar policy.

At the other end of the scale, 44,000-home Bromford says such a step is out of the question unless the lease contains “a mandatory buy-back clause”, which only applies to a tiny handful of its homes. However, the Midlands landlord takes “an open approach to subletting”.

Likewise, 65,000-home Notting Hill Genesis (NHG) says it is “very unlikely that we would buy back a property in these circumstances”, but lays out a clear “subletting procedure”.

“While our leases generally forbid subletting, we can consider requests on a case-by-case basis,” it explains. “One of the circumstances in which we allow subletting is where the need to sublet stems from a genuinely unavoidable need and is not primarily for speculation or gain. Cases where a leaseholder has died may fall under this criterion.”

Generally, NHG would permit the inheriting leaseholder to sublet only for 12 months, but it may review the situation if the property remained unsold after that time despite “genuine attempts” to sell.

Government guidance on shared ownership permits “leasehold repurchase” for most grant-funded homes where “the property is no longer suitable for the leaseholder’s needs”. The differing attitudes to buy-backs among providers may stem from wider business considerations. Having large numbers of unsold homes on the books can be financially risky and some organisations will feel more comfortable with that than others.

In addition, housing associations must sell shared ownership properties at a lower equity stake to keep them affordable – which some may be loath to do. That said, it is easy to see how someone inheriting 25% of the equity of a property that they have no interest in keeping might expect whoever owns the remaining 75% to take it over.

“We understand that the death of a friend or a relative is a very difficult time and when the person involved is actively doing everything that they can to meet their obligations, we will always do our best to help and support them in every way that we can”

There are also variations in approach to subletting. For example, unlike Bromford or NHG, L&Q says it will only permit the practice “in some very limited circumstances” following the death of a shared owner. Most respondents did not mention subletting at all.

In line with government guidance, a standard shared ownership lease forbids subletting except in “exceptional circumstances”. The rationale is simple: to prevent anyone profiting from affordable housing.

“I suspect how that’s interpreted may differ between organisations,” notes Mr Millns, whose own organisation would consider subletting where necessary.

Government guidance is clear it is in providers’ power to grant permission if they consider certain questions, such as whether the desire to sublet stems from “unavoidable need” rather than “speculation or gain”. But it is down to individual housing associations to decide whether struggling to sell a home you have inherited following a bereavement constitutes exceptional circumstances.

As Mr Millns sees it: “We understand that the death of a friend or a relative is a very difficult time and when the person involved is actively doing everything that they can to meet their obligations, we will always do our best to help and support them in every way that we can.”

From a strictly legal perspective, the situation is relatively simple. Neil Lawlor, a partner at Devonshires, explains: “Being completely dispassionate, the monetary obligations on a shared owner when they’re alive are significant. The thing to remember is those obligations don’t cease when that person passes away. Instead, it will fall with their estate.”

Complications usually tend to arise when it is unclear who is handling that estate, Mr Lawlor notes. If it isn’t stipulated in a will, there may be a long delay before anyone comes forward, during which time the lease liabilities will accumulate and the mortgage lender may try to repossess the property.

“Someone in the stressful situation of dealing with a loved one’s estate when they have passed away may see the demands as unreasonable”

“It’s not always clear what to do with a property when there’s no one to meet those obligations,” he says. “In those cases, we’d look at how we could get the property back to the housing association or whether it is best to work with the lender.”

But straightforward legalities do not always equal an easy process. “In practice, you’re dealing with people who may not have much knowledge about the terms and who may be grieving,” Mr Lawlor acknowledges. “Someone in the stressful situation of dealing with a loved one’s estate when they have passed away may see the demands as unreasonable.”

That certainly rings true for Ms Ashcroft, who insists the lease on her mother’s flat did not mention posthumous rent obligations and questions whether it is morally right that this should pass to an executor.

Her experience highlights why it is vital for housing associations to take an adaptable and supportive stance. “The answer is to have broad policies with the flexibility to deal with individual circumstances,” says the CIH’s Ms Davis. “You can understand why organisations have different approaches, but the important bit is how they respond to individual circumstances to reach an acceptable solution. Taking all the factors into account, it’s not easy.”

“It would have been great if someone had said, ‘We’re going to put you through to our bereavement team, they’re going to tell you what you need to do.’ It would have been useful if they could have offered help at a time that was really difficult”

Much of Ms Ashcroft’s complaint links to common criticisms of shared ownership – chiefly, that buyers may only own a portion of the property but essentially take on all the associated financial risk. Changing that would require legislative reform. But she also raises points that housing associations can consider now.

“I’d never dealt with shared ownership before, so it wasn’t that easy to work out what was required of me as executor to make a resale happen,” she reflects. “It would have been great if someone had said, ‘We’re going to put you through to our bereavement team, they’re going to tell you what you need to do.’ It would have been useful if they could have offered help at a time that was really difficult.”

None of the housing associations Inside Housing contacted mentioned having a dedicated bereavement team. Ms Ashcroft’s experience shows it may be worth thinking about whether it would be beneficial to train their staff in this area.

Shared ownership is still a relatively niche product – it currently represents only around 200,000 homes across the UK. But in a decade’s time, that figure is set to be significantly higher. These difficult questions about what happens after a resident dies will need to be settled sooner rather than later.

Sign up for the IH long read bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters