You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Gresham: how the housing market failed a community

During the summer, the National Housing Federation called for action on what it described as “left-behind places” in the North and the Midlands. As part of a series of reports from some of the most deprived areas in the country, Gavriel Hollander visits Gresham, Middlesbrough, to find out what market failure looks like. Photography by Gavriel Hollander

“There’s something about poverty that creates apathy,” muses Angela Lockwood as she crosses Union Street in Gresham, Middlesbrough. “When people are worried about how to put food on the table they don’t have time to be worried about housing issues.”

Ms Lockwood, chief executive of North Star Housing Group, has joined Inside Housing for a quick walk around the eerily quiet lunchtime streets in one of the most deprived areas of the country.

Empty homes proliferate, there are few shops other than the row of takeaways on the relatively bustling Parliament Road, and the streets are punctuated by people clearly drunk or high, studiously avoided by the occasional mother with a pushchair. Behind one boarded-up house we can hear a dog barking. When we go to investigate, two men appear from behind the door, looking furtive. There are houses openly used as hubs for drug dealers, while after-dark prostitution is rife.

Gresham is just across a main road from the shops and restaurants of Middlesbrough’s commercial centre, but it is an unwelcoming place. It is also almost unimaginably poor. Newport – the new name for the council ward that was previously Gresham – is in the bottom 1% of all wards across England on the government’s Index of Multiple Deprivation.

At the time of the 2011 census, unemployment in Gresham stood at 25.8% compared with 14.4% in Middlesbrough generally and 7.6% in England and Wales. The proportion of people classed as ‘economically inactive’ was 40.6% – almost double that of the country as a whole.

Those figures are nearly a decade old but walk the streets here or talk to the local people and it is hard to imagine that they will have improved by the time of the next census in 2021.

Explaining how Gresham got to this point is a complicated process. There is the long view, familiar to communities across large swathes of the post-industrial North East: as the traditional steel and shipbuilding industries of the region declined and were eventually killed off, jobs became scarce, people fled south and the economy stagnated.

But more recent events have also had a role – these centre on housing policy. In 2010, the coalition government pulled funding for the Housing Market Renewal (HMR) pathfinder programme (see box below), which left many areas – especially in the North and Midlands – with half-completed demolition jobs and little money to clear up the mess.

In Gresham, plans to bulldoze and redevelop dozens of streets were dramatically scaled back. For several years the council had been buying up properties in preparation but in the end only half of the roughly 1,500 homes originally earmarked were demolished.

A council report from September 2011 predicted what was to come: “The immediate cessation of funding has left residents in streets with many boarded-up properties,” it said. “In such circumstances it is difficult to revitalise such areas.”

A false dawn: the Housing Market Renewal programme

Picture: Rex Features

The Housing Market Renewal programme was launched in 2002 as the brainchild of then-deputy prime minister John Prescott (above). The aim was to encourage investment into places where there had been low demand for housing by embarking on a programme of demolition, refurbishment and regeneration.

Nine areas in the North and the Midlands were nominated as pathfinder programmes in 2002, with three more (including Tees Valley, which included Gresham) added in 2005.

The programme was highly controversial and attracted criticism for its focus on demolition. But when it was abruptly halted by the coalition government in 2010, some of the pathfinder areas were only halfway through their programmes.

The housing minister at the time, Grant Shapps, released £35m in a ‘transition fund’ for the councils involved but many of them had to subsidise this themselves in order to complete demolition work, while virtually none was spent on refurbishment.

Kevin Parkes, executive director of growth and place at Middlesbrough Council, was the author of that report. He remembers the thinking behind the demolition programme well.

“We decided that the time was right to intervene in the market,” he tells Inside Housing. “One thing you learn is that you sometimes get intoxicated by the environment around you. And so when the money was cut off in late 2010 we were mid flow in acquisition. We found ourselves in a position where we had partly acquired areas and partly unacquired areas.

“There was a perception that there would be another fund. Thinking about where we were then, I remember the chief executive in 2010 saying austerity would be a one or two-year thing and it’s been part of our lives for a decade now. With HMR, we had a false sense of security that there would be something that would pull us through to complete the programme.”

Nothing came along. Instead, in 2013 the council felt it had no choice but to row back on its plans. The scars from this period can still be seen today. On a patch of land to the south-east of Union Street, which cuts through the heart of Gresham, pairs of houses stand on their own, semi-abandoned – while around them a muddy wasteland has been turned into an ersatz car park.

While the HMR programme was intended to attract a new breed of homeowners to the areas in which it was deployed, what has happened instead in Gresham and elsewhere is that private landlords have taken over.

The quiet streets of Gresham in Middlesbrough

Census data shows that in 1991, owner-occupiers made up 78% of all housing in Gresham. By 2001 that figure was 50% and just 32% by 2011. Over the same period, private rented housing grew from 16% of homes in the ward to 47%. Most people here expect the 2021 figures to show private rented homes comfortably making up the majority. For some context, across the whole of Middlesbrough in 2017 owner-occupiers made up 57% of housing and private rent just 17%.

The effect of such a fundamental shift in property ownership into the hands of private landlords has been dramatic.

Earlier this year, the National Housing Federation’s (NHF) Great Places Commission released a report calling for greater government investment in what it described as “left-behind places”. Gresham was one of the stops on the commission’s itinerary.

“Of everywhere we visited, this is where we decided public money was most needed,” says Ms Lockwood, one of a dozen commissioners on the report.

It is a sentiment that is echoed across the community. “There has been zero investment in Gresham, literally zero,” agrees Bini Araia. “It is an ignored part of Middlesbrough.”

Mr Araia arrived in Gresham in 2001 as an asylum seeker from Eritrea. When he landed at Heathrow, having suffered malnutrition as a political prisoner back home, he weighed 35 kilos and had $100 in his pocket.

“There has been zero investment in Gresham, literally zero. It is an ignored part of Middlesbrough”

Now, he runs The Other Perspective – a community interest company that, among other things, helps local people find employment – and is an advocate for Gresham. He loves the community that gave him a second home but is not blind to its problems.

“It has been neglected for a long, long time and it needs a proper rethink in terms of housing, of community cohesion and the way that’s done at a grassroots level,” he continues as he gives Inside Housing a tour of the area.

Mr Araia found himself in Middlesbrough thanks to the Home Office’s asylum seeker dispersal programme. Because of the availability of cheap housing, the town has one of the highest proportions of asylum seekers in the country – and the new arrivals are now an integral part of the fabric of life in Gresham.

But the communities of Poles, Romanians, West Africans and others can be easy prey for often unscrupulous landlords. In a council survey of housing conditions in 2008, 49.3% of private homes in the Parliament Road area were found to be ‘non-decent’, compared with 24.6% in Middlesbrough as a whole and 27.1% in England.

Many homes are boarded-up and semi-abandoned in Gresham

“The rent is not necessarily cheaper but the quality is extremely poor,” explains Mr Araia, when describing the condition of the housing. “There are health hazards, roofs falling apart, major damp problems. But people don’t have a choice; if they cannot get into social housing then they have to go to private landlords.”

So where are the social landlords? The NHF commissioners were all drawn from the ranks of senior association executives. But the commercial pressures on many housing associations makes building in places like Gresham economically impossible.

North Star has around 100 properties in the ward and the other major local landlord – Thirteen Group – has just over 500. Thirteen is also partnering with the council to build another 179 homes as part of a development that includes a new student village for Teesside University. Welcome as this is, it is hardly transformative for an area of more than 5,000 properties.

Ms Lockwood is candid about why North Star is not adding to its stock in Gresham: “We cannot have any more properties here – it’s too expensive. Every house we took on, we would lose money on it from day one.”

Annual tenant turnover for North Star’s homes in Gresham is 40%, against 14% for the rest of its stock. The average tenancy is 36 months, compared with more than five years in other areas. Meanwhile, private landlords can buy a three-bedroom terraced house for as little as £40,000, allowing some to build large portfolios with relatively little investment.

“We need acquisition and demolition,” Ms Lockwood answers when asked about solutions to Gresham’s problems. “HMR had many flaws but it had the right focus on demolition.”

Gresham seems to be a symbol of what happens when social landlords are unable or unwilling to build homes for the people they were set up to help in the first place. If social housing is a safety net, this is a community where many residents have slipped underneath it.

“The best thing that could happen would be for Thirteen and North Star to build properties here,” says Kim May, operations manager of Streets Ahead, a charity that provides information and support to the Gresham community. “If you could get good rental housing here it would pull the area up.

“We’ve got landlords who own properties you wouldn’t want to walk into, let alone sleep in. And we have young people who have no option but to sleep there.”

Ms May has worked at Streets Ahead in Gresham since 2006. She believes the social problems that have always been close to the surface have got worse in recent years, particularly since the austerity-driven cuts to public services began to be felt.

Resident Bini Araia believes a rethink for housing community cohesion is needed

“People are openly dealing from street corners and from houses,” she continues. “I put it down to the fact that there’s not as many police officers around. Dealers feel emboldened.”

Her theory has some evidence behind it. Earlier this year, Cleveland Police became the first force in England and Wales to be rated inadequate. That followed a 37% reduction in staffing and £25m budget cut over eight years.

Calling somewhere like Gresham “left behind” has almost become a cliché, but Ms May says it is a fair reflection. “That is how people feel. They think everything happens in London – and there’s no point in voting because what difference will it make? There are people here who are completely disillusioned – they’ve lost all hope.”

Not far away from Streets Ahead, Susan Gill runs a cafe for the homeless on Princes Road. Round a couple of corners, designer clothes shop Psyche sells hoodies for £150. But here, Ms Gill hands out free meals to around 60 people a day – mostly men and mostly current or former addicts. She shows Inside Housing photos on her phone of the 10 people whose funerals she has attended since April.

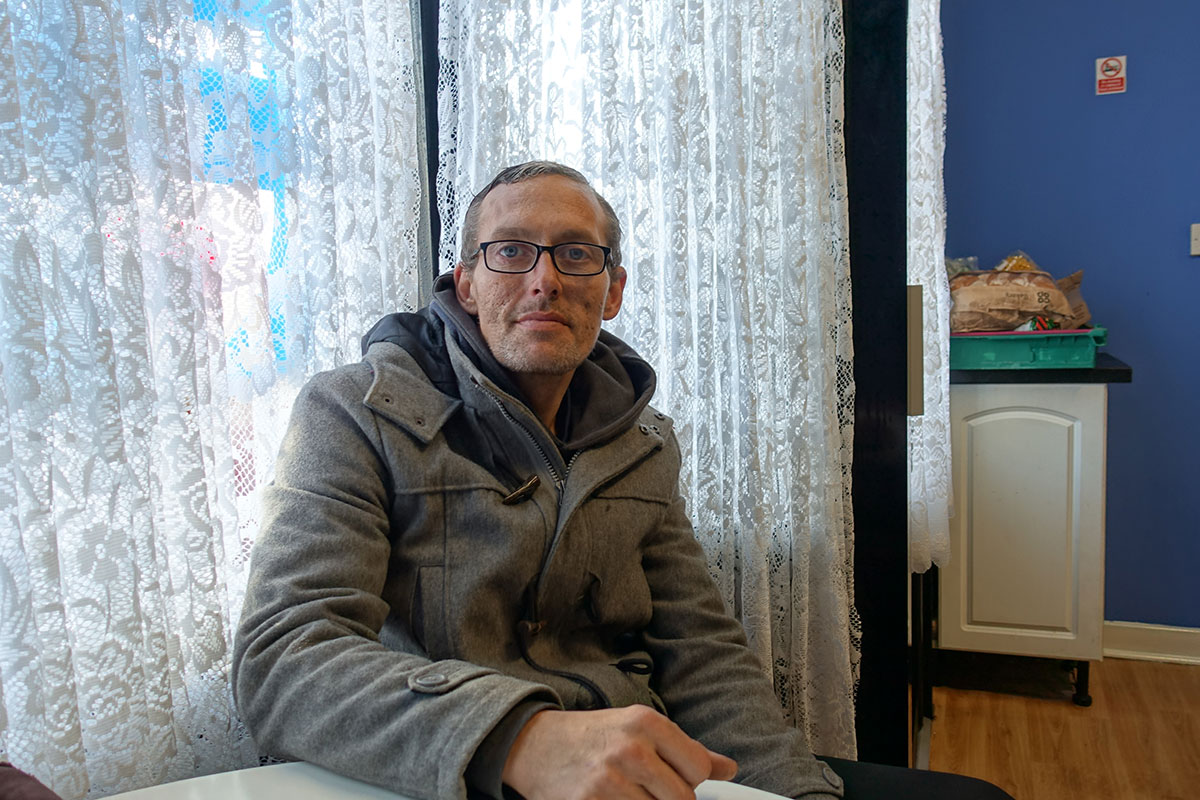

Gary Bilton, 44, was an addict for 16 years but has been clean for the past seven. He is from Gresham and is a regular at the cafe, although he has now found a place to stay near The Avenue in the neighbouring ward of Linthorpe.

“That is how people feel. They think everything happens in London – and there’s no point in voting because what difference will it make? There are people here who are completely disillusioned – they’ve lost all hope”

“It’s horrendous,” he says, recalling his time as a tenant in Gresham. “Most people would rather be on the streets. There are lots now who just hang around taking drugs and getting smashed off their face.

“You would phone up to say you had a leak and four weeks later no one has come and it’s through the roof. Landlords are just taking advantage of the vulnerable.”

The vocabulary of Gresham is bleak. People talk of giving up hope. Drugs and crime are clearly a huge problem, and they are the things that the town’s new mayor, Andy Preston, has put at the centre of his strategy.

“I’ll be blunt: it’s in a shocking state,” he says. “Gresham is what differentiates Middlesbrough from other post-industrial towns and cities. To have that scale of dereliction, deprivation and despair abutting the shopping districts is highly unusual and completely unacceptable.”

Mr Preston was elected in May as an independent, and his plan for the area involves the recruitment of what he calls “an army of street wardens” to patrol the neighbourhood and the introduction of public space protection orders, outlawing anti-social behaviour such as begging.

Former Gresham resident Gary Bilton is a regular at the cafe for homeless people

The plans have been criticised by human rights organisation Liberty as attacking homeless people. But Mr Preston is adamant that tackling drugs and crime is the priority, and it has been ignored by previous administrations.

“Politics here have behaved like an addict with its refusal to accept the scale of the problem,” he explains. “You cannot recover until you admit the scale of the problem and that it’s out of control. Politicians here – the MPs, the councillors and the prevailing powers – never talked about it. It was the unspoken issue.”

He also points to the new housing being built with Thirteen and the student village as signs that Gresham can turn a corner. Meanwhile, a pilot selective landlord licensing scheme has been brought in with the hope of curbing some of the excesses of the private sector, although there have been few prosecutions so far.

For many of the people of Gresham, it is to be hoped that such projects bring about real change. And quickly.

At Streets Ahead, Ms May sums up the prevailing mood: “If you did a mental health survey, I think you would be scared by the results. The one in four would go out the window. A lot of people round here think it’s just part and parcel of life.”