You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

A guide to the history of council housing in 100 estates

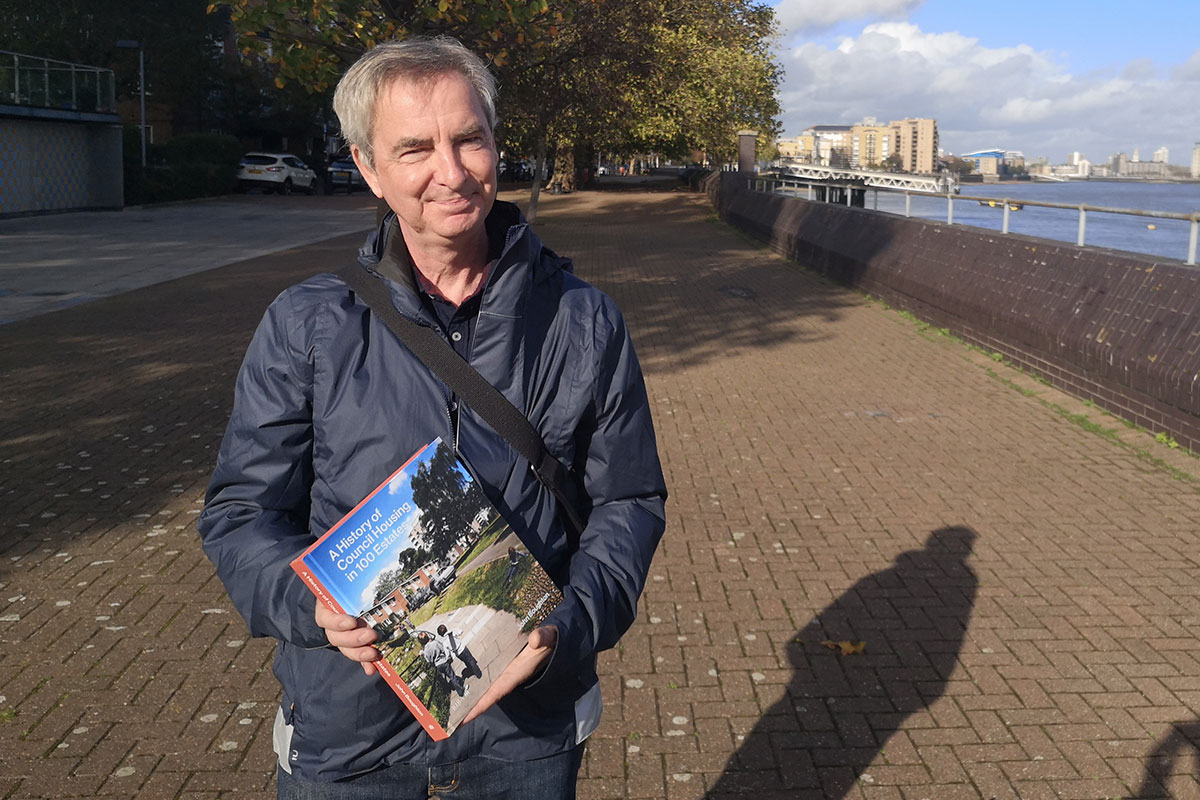

John Boughton has written a new book that looks at iconic council estates. Peter Apps meets him to find out more about this forgotten history

What are the buildings that tell the story of our history? Classically, the answer would involve monuments, castles, churches and other seats of religious and political power.

But the history John Boughton wants to tell is found somewhere else: the UK’s social housing estates.

“Local histories will tell you about the Georgian townhouse, but they won’t tell you about the neo-Georgian council estate,” he says. “But which was more important to the people who lived in that town? It’s been criminally neglected as part of our shared story.”

Mr Boughton’s new book, A History of Council Housing in 100 Estates, seeks to fill that gap.

A social historian, he has carved out something of a niche in this area. His blog, Municipal Dreams, was a passion project he started after a career as a teacher.

He says that while he had uncles and cousins who lived in social housing when he was growing up in Norfolk, he has no “lived experience” personally. Where, then, does the interest in public housing spring from?

As a social historian, he had grown interested in “the role of local government, which I think is undervalued particularly in the British context”, he says. “Housing is the largest intervention that local councils made.”

The Municipal Dreams blog later became a well-received book documenting the history of council housing. It was published in 2018.

This new work covers similar ground but approaches the topic differently. Each era of public housing policy is documented by entries on the estates which are that era’s legacy; running from an 18th century almshouse in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, through to Goldsmith Street in Norwich. The latter is the beautiful and environmentally conscious scheme of 100% social housing, which made headlines by winning the Stirling Prize in 2019.

‘Telling the longer story’

The steady, often faltering history of our efforts to provide decent housing to those who otherwise could not afford it, is recorded in the bricks and mortar that resulted from these efforts. Some were triumphs, others were disasters – many had moments of both.

Mr Boughton is an erudite guide through this story. He meets Inside Housing on the Pepys Estate (one of the 100) in Lewisham, south-east London, and takes us on a fascinating walking tour of a place that is a story of success and failure.

“With MMC, it’s perfectly possible this time we might get it right and we’ll do it better. But we need to be realistic about how it’s gone in the past”

The book (which has been published by the Royal Institute of British Architects and retails at £40) is more of a coffee-table tome than a casual read, but the images alone justify the cost. It is a tour of places unknown to those who do not live there and it is easy to lose several minutes every time you open the book and flip through the glorious mix of archive and contemporary images.

“I just thought it was a good way of telling the longer story,” Mr Boughton explains. “It wasn’t intended to be a collection of iconic estates or yet another celebration of brutalism. I really just wanted to sort of present council housing as it is, in its ordinariness and its diversity.”

Among many striking things which come across from reading it is a reminder that the debates in the sector today are often an echo of much older conversations. The conversation about whether modern social (affordable) rents are truly affordable sometimes feels like a very contemporary concern. In fact, the trade-off between cost of construction and the ultimate rent charged is one that has plagued the sector from the beginning.

“When you see the common sense of one era completely contradicted by the new ideas of the next, that makes you very humble"

“Rents ranged from 5s (30p) to 11s 6d (57.5p) per week,” Mr Boughton writes of the Burnage Garden Village in Levenshulme, Manchester, built in the 1900s. “At a time when the local working class were generally paid not more than seven shillings weekly (35p)… this sum clearly precluded most from benefiting from the new estate.”

Modern methods of construction (MMC) also appear to be a misnomer. Mr Boughton visits factory-built estates dating to shortly after World War I, such as the domed, barn-like curved roofs of the Nissen-Petren houses in Yeovil, Somerset, or the ill-fated ‘Boot Estate’ in Liverpool.

“I’m certainly struck by the fact that these kinds of ideas and questions kind of resurface every 10 or 20 years,” he says. “With MMC, it’s perfectly possible this time we might get it right and we’ll do it better. But we need to be realistic about how it’s gone in the past.”

One thing Mr Boughton is keen to avoid is any suggestion that a certain type of estate ‘works’ and others do not. Most, he says, have periods of success and harder times, which often result from factors far removed from the architecture or the planning.

“Most people will want some definitive judgement about how this work[ed], this didn’t and this is what we should be building now,” he says. “But when you see the common sense of one era completely contradicted by the new ideas of the next, that makes you very humble. I think the biggest lesson for me in this is humility. Obviously one wants architects to bring real care and attention to their designs, and planners likewise. But one also has a very powerful sense that they don’t actually determine the success or failure when there is so much going on that is external.

“Most people wanted a front door, a decent, secure and affordable home, and council housing in all its forms almost invariably provided that.”

Throughout the book, a similar quote keeps emerging. New residents who move into the homes describe it as “a palace”, “heaven with the gates off” or something similar. Mr Boughton includes these quotes for some estates where the reputation may – perhaps unfairly – suggest something different, such as Pollok in Glasgow or Creggan in Derry. Was he trying to make a subtle point?

“It’s interesting you noticed that… because I try not to repeat those quotes too often. They’ve become clichéd,” he says. “I could probably have found a quote like that for every one of the hundred estates. But that just goes back to the essential decency of council housing. People were moving from far inferior conditions and for most that was almost a revolutionary change, and that’s repeated more than five million times.”

There is much to take from this book. Each one of the estates could make an interesting feature for Inside Housing, and it raises some interesting areas of partially forgotten policy choices.

I did not know until reading it, for example, that the houses familiar to me from friends who moved out into West Essex in our teenage years were an example of the Radburn philosophy in the 1950s: homes that opened onto large greens instead of streets. And how this philosophy faded as the idea of ‘defensible space’ was imported from the US in the 1980s.

“There’s a lot of middle-class concern about how working-class people live their lives,” Mr Boughton says. “A lot of that stuff is well meaning, so you have from the 1930s, and again into the ’50s and ’60s, these various attempts to engineer community. But that almost never works; community arises through the dynamics of the tenants who live there.”

“I do think we are moving forward, moving to an era where public housing is going to be more important, more valued, better understood as a necessary component of a mixed economy of housing”

Having tracked this history, how does Mr Boughton feel about the future? There are reasons for optimism, but also – when you consider how far we have fallen from the days when one in three people lived in secure council housing and the stilted progress in so many areas despite a century of work – reasons for despair.

“I feel more optimistic,” he says. “It’s easy to be caught in the immediate political moment when there’s no reason to be positive whatsoever. But councils want to build. And I do think we are moving forward, moving to an era where public housing is going to be more important, more valued, better understood as a necessary component of a mixed economy of housing.”

One of the best ways to understand this is to simply look around at the estates that have risen from the ground over the past 100 years and the enormous role they played in increasing the living standards of the millions who have passed through them in that time. Mr Boughton’s wonderful book is a vital record of that.

The Pepys Estate in Lewisham, south-east London

A former 16th century dockyard on the banks of the River Thames, not far from maritime Greenwich, the estate wears its naval history proudly. John Boughton points out a plaque noting its opening by Lord Mountbatten and the ceremonial cannons placed by the waterfront.

The estate was sold to London County Council by the admiralty for housing in 1958, with the 1,500-home estate opening in 1966. Some old naval buildings, including rum warehouses, were converted at great cost into housing.

Originally a series of 10 eight-storey, medium-rise blocks and three 24-storey towers, the estate was designed with large open spaces for children to play and walkways that separated the community from traffic. “You could walk from Deptford Park to the river with your feet never touching the ground,” says Mr Boughton.

But things went wrong. There was a policy of nominating only white tenants to the estate in the 1960s and early 1970s – something a former housing officer has admitted was based on the assumption that “Black and white [people] would rather live separately from one another”.

As this discrimination softened, non-white families began to arrive and tensions rose. As unemployment soared and funds to maintain council housing dried up in the 1980s, some older, white residents began to blame emerging problems on their new neighbours.

In the 2000s, the estate was transferred to Hyde Housing. Several of the medium-rise blocks were demolished and new housing erected in their place, with a net loss of 366 social rent homes. Local councillors spoke openly of a desire to “break up” the “monolithic concentration of public housing… and bring in a different mix of incomes and people with spending power”.

Controversially, the 144-home Aragon Tower, one of the three tower blocks and the one located closest to the river, was emptied and sold to private developer Berkeley for a pitiful sum of £11.5m in 2002. It is now glossy, private housing with penthouse apartments added at the top. Two-bed flats here now sell for well over half a million each.

Today, the estate shows the scars of the modern building safety crisis: Aragon Tower was found to have missing fire breaks and residents were forced into a row with Berkeley about who should pay. Several of the blocks built in the 2000s are having cladding and insulation removed when we visit. The remaining concrete medium rises by contrast look calm and peaceful, with children playing on the remaining balconies and walkways as they have done for nearly 60 years.

Sign up for our Council Focus newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters