You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

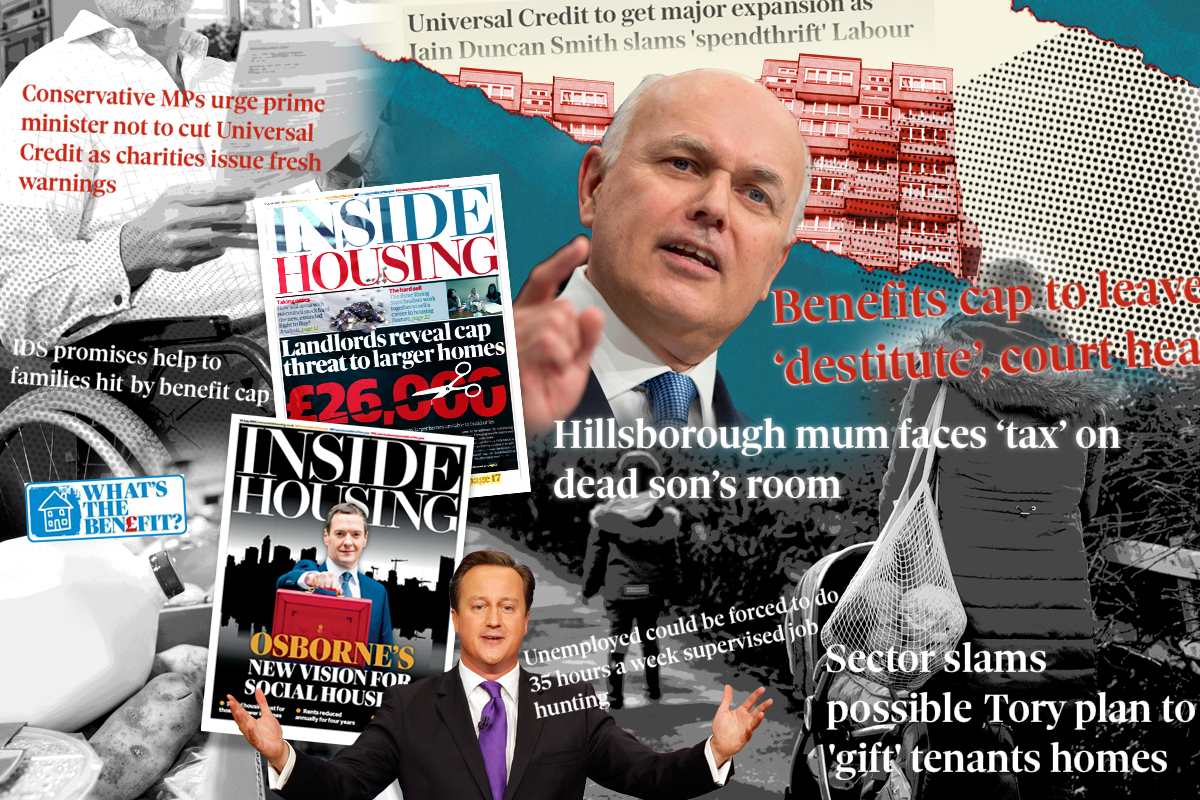

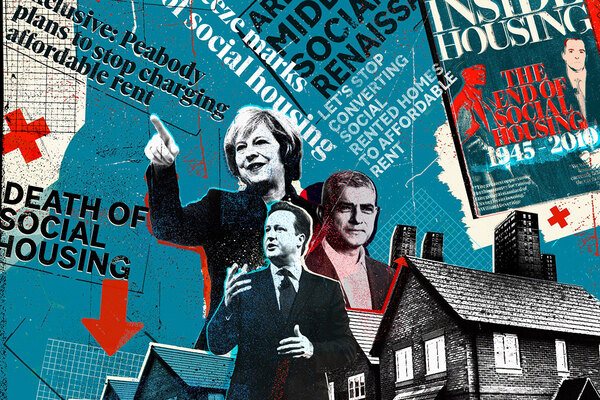

10 years of welfare reform

Yesterday we published our analysis of the impact of 10 years of affordable rent on social landlords and tenants. Today, we publish the second instalment in our series – examining 10 years of welfare reforms. Jess McCabe reports

When prime minister David Cameron unveiled the welfare reforms in February 2011, he called them “the most ambitious, fundamental and radical changes to the welfare system” since it was created.

A package of cuts and changes, this reset the benefits system. One aim was to cut £11bn from the welfare bill. The other was to reconfigure benefits for people of working age to incentivise employment. One of the key words used in many government communications at that time on these policies was “fairness”.

“Inside Housing reported the start of the bedroom tax in April 2013 as “the day so many people have been dreading”

There were many strands to the reforms – too many for us to detail here, including some significant ones such as radical changes to benefits for disabled people and hardening the regime of benefit sanctions.

But the most significant for housing were:

- The bedroom tax, which cut house benefit for social tenants deemed to be under-occupying their homes

- The benefit cap, which limited the total amount of benefits a household was entitled to

- The introduction of Universal Credit, to replace six working-age benefits, including housing benefit. This was to be a single payment per household once a month. Significantly, the housing benefit element of this would be paid directly to the nominated person in the household, rather than directly to their landlord

- Cuts to Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates, which limited the amount of housing benefit that a household could get from median local rent to the 30th percentile

To give a sense of how these changes were received, Julia Unwin, at the time chief executive of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, warned of a “decade of destitution”. Inside Housing reported the start of the bedroom tax in April 2013 as “the day so many people have been dreading”.

Stories from people affected quickly began to emerge, taxing the notion of “fairness” of the reforms. To give just one of countless examples that ended up in media reports when the bedroom tax began in 2013, there was Angela Hooper, a five-year-old disabled girl whose parents were charged the bedroom tax for her specially built bedroom.

A total of 350,000 people visited The Trussell Trust foodbanks in 2012-13, a three-fold increase. This shocked people at the time; by 2020-21, the number of foodbank visitors had reached a staggering 2.5 million people.

It was particularly feared that the bedroom tax would drive poverty among social tenants who would find themselves unable to move home, and create huge arrears for social landlords as their tenants couldn’t make up for the shortfall. The policy only lasted nine months in Scotland, after the government stepped in to cover the policy with a dedicated discretionary housing payment fund.

Lots of tenants did move to smaller homes, but in many places there simply weren’t the homes to move to. For some tenants this did lead to evictions. Inside Housing understands in the years since, many councils have just accepted that many tenants will need Discretionary Housing Payments (DHP) in perpetuity to make up the gap, and the cost to government has just shifted from housing benefits to DHPs.

Legal cases

A number of legal cases have also softened the blow for some specific groups of people moving forwards – in 2019 the Supreme Court ruled that a man who couldn’t sleep in the same bedroom as his wife because of her medical equipment should not have been charged for the ‘extra’ room. The same year, the European Court of Human Rights ruled the bedroom tax didn’t apply to panic rooms installed for domestic abuse survivors.

“Many customers report increased strain on mental health as they struggle to survive”

The bedroom tax was the most high-profile initial reform, and the one that had arguably the most immediate and direct impact on large numbers of social tenants. But over the long term, other reforms have hit hard as well. Glasgow’s Wheatley Group, for example, has not been impacted by the bedroom tax since the Scottish government stepped in. But it says of the other reforms: “We’ve seen a huge increase in customers seeking help because of food and fuel poverty and the five-week wait for first UC [Universal Credit] payment. More customers in rent arrears who hadn’t been in arrears before. Many customers report increased strain on mental health as they struggle to survive.”

Reflecting on the past 10 years, landlords say the impact of Universal Credit has been harsh, in particular the longer wait before the first payment (six weeks initially was reduced to five weeks in 2017). “The knock-on impact of this was that we saw more cases moving into escalation and court, as well as the increased level of evictions,” Cross Keys Homes told us, one of many to also talk about the mental health impacts on tenants increasingly worried about their finances.

Around 62% of Incommunities tenants are currently in arrears, and the landlord told us: “Many of our customers who are affected by welfare reform live below the poverty line or are just about managing. Income shocks for customers living in this way mean customers have to make a choice between heat or rent, food or rent, food or heat, etc, as well as learning how to manage a single monthly payment of Universal Credit. For many this is completely overwhelming.”

London-based housing association Catalyst says: “The five-week waiting time means many residents are requesting an advance, then the repayment impacts their budget, especially if they end up repaying arrears accrued early on via a third-party deduction. Single residents are often left with very little money for essentials.” It adds: “Frontline staff spend a lot of time submitting DHPs to pay for bedroom tax and benefit cap shortfalls.”

A Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) spokesperson says: “Universal Credit has delivered from day one and has gone from strength to strength. It stood up to the challenge of the pandemic, successfully managing claim volumes the legacy system wouldn’t have coped with.

“As a result, millions more people can access a welfare system which is fairer and more generous than the one it replaces.”

At the same time, though, the past decade has seen a rise in “in-work poverty”, with more people on low-paid and insecure work. Joseph Rowntree Foundation research from before the pandemic found that there were four million “workers in poverty” in the UK in 2017-18, and that once someone was in low-paid work it was harder to get out of it. This has posed significant problems for social tenants managing their income, landlords told Inside Housing.

“Work is the best route out of poverty and the changes we have made to the Universal Credit taper rate will see nearly two million working households better off by around £1,000 a year,” the DWP spokesperson says. “Combined with our work allowance increase, this represents an effective tax cut of £2.2bn. The taper rate is much fairer than the legacy system, where claimants faced a cliff-edge of support. Instead, benefit payments are now reduced consistently by 55p for every £1 of earnings, meaning claimants have certainty on their income and there is a strong work incentive.”

LHA reduction

The LHA rate reduction has undoubtedly hit hardest for private renters. Initial proposals to cap LHA for social renters, including people in supported and sheltered housing, were announced in 2015, and led to an almost complete halt in development of supported housing. The idea was abandoned before it was implemented.

The benefit cap is another policy which has been felt to the most extreme degree in the private rented sector.

“It is not because tenants have decided to rent houses above their financial means, it is because we are stuck here and we are being severely punished for that”

Set initially at £26,000 a year then cut in 2016 to £23,000 in London and £20,000 everywhere else, the aim of this policy was to avoid households receiving perceived high amounts of benefits in comparison to people in work. However, all analysis shows that the impact has been felt largely by single parents – of which 90% are single mothers – and disabled people, who have limited ability to find employment or move to cheaper areas.

Laura, a single mother in a private rented flat in London, shared with Inside Housing a screengrab of her benefits information, which shows the cap reduces her monthly income by £522.81. “It absolutely has worsened over time, and it’s not just the cost of housing that has increased. All household bills are rising all the time,” she told us.

“There really is no escape from it – as far as the local authority are concerned I am housed so they have no duty to me. Private landlords don’t want (or need!) to rent to me to attempt to reduce the burden of rent. I think it is the impact on well-being that I feel the greatest.” She adds: “It is not because tenants have decided to rent houses above their financial means, it is because we are stuck here and we are being severely punished for that.”

“Council housing tenants in particular are relatively lucky – some of the greatest concerns are people who aren’t in the social housing sector,” notes one local authority expert Inside Housing spoke to for this story.

“The benefit cap ensures fairness for hard-working taxpaying households and a strong work incentive, while also providing a much-needed safety net of support for claimants,” the DWP spokesperson said, while also noting that people struggling with costs can apply for DHPs from their council.

Social landlords know of only small numbers of their tenants having their benefits capped: Beyond Housing, for example, has nearly 15,000 homes, and knows of 66 having their benefits reduced because of the cap. Notting Hill Genesis told us 473 of its tenants are capped, out of more than 66,000.

The true numbers could be much higher, however. Laurinda Hornblow, strategic head of income at Sovereign, says: “We do not know who receives what. We’re in the dark until we fall over the fact that they stop paying their rent.”

In response to the welfare reforms, landlords have staffed up and set up numerous initiatives aimed at helping residents navigate their way through the benefit system, maximising what they can claim, and helping access other support.

Citizen, a 30,000-home social landlord, is completely typical in having hired people to provide advice on money management, benefit applications and employment coaching. It says: “We feel this is essential support for our customers and a significant element of our income-recovery strategy.”

“There’s always something we can do,” says Ms Hornblow of Sovereign. Behind the scenes of housing associations and councils, job roles have changed significantly in response. “It’s completely changed the whole approach to what the traditional income officer would do 10 years ago – make sure the housing benefit was being put in place, go and collect the rent,” she adds.

Over time, the government has made further changes to welfare.

When the Conservatives won an overall majority in 2015, a further tightening of rules and cuts quickly followed. Iain Duncan Smith, the architect of these changes, dramatically resigned in 2016, citing the level of cuts to Personal Independence Payments to disabled people. His resignation talked about frustrations over the “salami-sliced” benefits policies.

But government has also softened the edges of the system for some claimants. Initially it was quite difficult for social landlords to apply to get the housing part of Universal Credit paid directly to them – that is now described by practitioners as relatively straightforward. “Several years down the line, it’s now very straightforward for a council or landlord to recommend an APA [Alternative Payment Arrangement],” one local authority source says.

Into this situation came the pandemic. Huge numbers of people went onto Universal Credit during the first lockdown, with a peak of six million. This had gone down slightly to 5.8m by mid-October. The housing benefit bill is predicted to be £30.3bn in 2021–22.

The government responded by adding £20 a week to Universal Credit, but there was outcry when it was cut again. Most recently, the DWP announced a reduction in the “taper rate” for Universal Credit, increasing the amount a household can earn before their benefits start being cut, which will benefit those claimants in work.

Other changes include the creation of a £500m support fund through which, the department’s spokesperson noted: “The most vulnerable, including those who can’t work, can get additional help with essential costs.”

There are also more impacts expected in the years to come. While most benefits are increased in line with inflation each year, the benefit cap has stayed the same since 2016. Housing consultant Joe Halewood notes that under the benefit cap, adult and child benefits “are deducted from the cap limit, which then leaves a maximum residual amount that can be paid in housing benefit (and Universal Credit housing cost element). Each year, the ‘other’ benefits increase by Consumer Price Index, leaving an ever reduced maximum housing benefit that can be paid because the cap limit does not get uprated.”

“It means shortfalls against your rent will become a permanent feature of the benefit system”

As social and affordable rents increase, more and more tenants will be left with a shortfall on their rents. Mr Halewood has already identified many local authority areas across London, the South East and some of the North, where a family with two children receiving benefits would start to be capped if they’re on social rent, with this expected to grow to spread even further if benefits and rents continue to increase with inflation, while the cap is kept at levels set in 2016.

Jules Birch, who has been following the changes in depth since the beginning, says: “It means shortfalls against your rent will become a permanent feature of the benefit system. You will have to make up your rent from your other benefits or help from family and friends – a further drift into destitution.”

Looking back on the impacts of the past 10 years, many people raised to Inside Housing the mental health impacts, as well as the financial impacts, on tenants. Optivo, for example, highlights: “There was the mental health impact given the pressures that this posed and the decisions that had to be made and a high number having to move away from family homes they had lived in for a considerable number of years.”

The past 10 years has also raised questions about whether the reforms have succeeded on their own terms. The changes were “all part of the view that the solution to poverty is work. And I think the past 10 years have demonstrated that’s not always the case”, Mr Birch says.

That has been particularly apparent given the increasing number of tenants who are working and still reliant on benefits to pay their rent and survive. The growth of low-paid, insecure work and zero hours was raised repeatedly by housing associations Inside Housing spoke to for this story. Meanwhile, council spending on temporary accommodation soared to £1.19bn in 2019-20, and the numbers of homeless households in this accommodation has almost doubled to 96,600 since 2010.

High housing costs are combined with low-paid, insecure work, meaning that getting a job is no longer a direct path out of poverty. The undersupply of affordable homes also comes into play. There is, as one analyst put it to Inside Housing, a “toxic relationship between under-investment in affordable housing and the benefit system”.

The future

What does this mean for the future? This is incredibly hard to predict. James Prestwich, director of policy and external affairs at the Chartered Institute of Housing, wonders if there is an opportunity for “a renewed dialogue” with government now. Times have changed – for example, the pandemic has highlighted the importance of extra space in a home, and perhaps could open a wedge for removing the bedroom tax.

On the other hand, Mr Birch worries that rising costs could instead bring back into play some of the harsher ideas of welfare reform that were abandoned in the past 10 years – like the original idea of cutting Jobseeker’s Allowance after a year of unemployment. He warns: “Looking to the future, you wonder, with the housing benefit bill still high, will there come a new drive from the Treasury to save money and will some of those old ideas get dusted off again?”

Sign up for our tenancy management newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters