You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

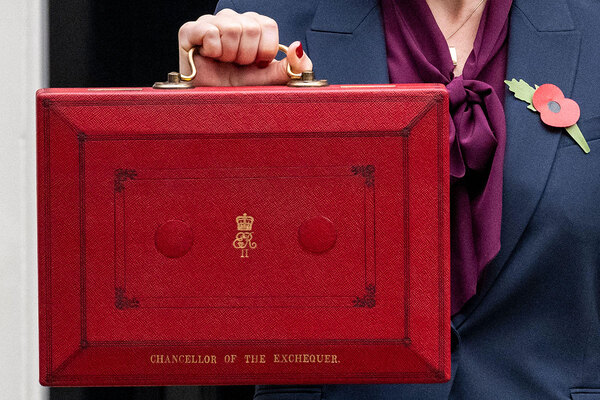

The housing sector’s post-Budget blues

The proposals in the Autumn Budget are nowhere near the radical steps the sector needs, writes Jonathan Cox, partner and head of social housing at Anthony Collins

It’s fair to say that Labour’s first Autumn Budget brought nothing momentous and provided no long-term solutions for the housing sector.

While welcome, the chancellor’s confirmation of additional investment for the Affordable Housing Programme (AHP) is little more than a drop in the ocean when taking into account how stock has dwindled over the years. With ambitious housing targets to meet in this parliament, the government must be aware that far more radical changes are needed to kick-start the delivery of social and affordable housing at scale.

The main reasons for the net loss in social housing, which has occurred every year since 1981, according to Shelter England, are well documented. Between 2022 and 2023, there was a net loss of 11,700 social rent homes. The Right to Buy scheme has led to the private sale of many council houses, and other factors, such as the rising cost of repairing and maintaining social rent properties and caps imposed on rents, have all had an effect.

No one in the housing sector thought that addressing the current shortfall in supply of social rent homes was going to be easy, but the measures announced in the Budget will have little impact overall.

The crown jewel in the chancellor’s housing pledges was its commitment to top up the AHP with £500m of new funding in 2025-26. This sum raises the annual budget for affordable housing to £3.1bn, the largest in over a decade. More funding is better than no funding, but the promised 5,000 additional affordable homes that the government claims will be created as a result of this capital injection is too few to make a difference.

It’s well known that a chronic failure from successive governments to drive affordable housebuilding has led to rapidly increasing levels of homelessness and overcrowding. While £500m is a step in the right direction, it doesn’t get close to addressing the social housing crisis that registered providers and vulnerable people are currently facing.

The government is well aware of this. The extra £233m to tackle homelessness and rough sleeping – therefore increasing that budget to £1bn – underlines its commitment to make a step change. However, if the government is going to truly make that step change in addressing the housing crisis in the long term, it must find other ways to increase funding.

“The Budget seems to have ignored the systemic issues that exist between housing associations and developers”

The Budget has at least acknowledged this by confirming the government’s intention to outline future grant investment, beyond the AHP, in Phase 2 of the Spending Review. This opportunity must be used to generate a sustainable funding stream for the sector that will make it possible to build 300,000 new homes per year.

Disappointingly, the Budget seems to have ignored the systemic issues that exist between housing associations and developers. Leaving the development of affordable and social housing exclusively to private sector property developers is creating more problems than it solves.

To explain, developers have historically operated on 40% profit margins when selling Section 106 agreements to housing associations, and few are willing to accept less. However, housing associations and other registered providers have limited means, and purchasing Section 106 agreements is often not financially viable or in the best interests of their organisation.

Why should registered providers, many of them not-for-profit organisations, be required to pay over the odds in this way for land to house some of the most disadvantaged and vulnerable people in society?

Many housing associations and other registered providers (RPs) believe Section 106 agreements should be sold at cost based on the cost of the build alone. The way things work currently means that private sector property developers are benefiting from a bidding war for development opportunities.

Rather than ramping up competition between registered providers in this way, wouldn’t it be better to introduce competition based on criteria that could improve tenants’ lives? For example, housing associations could compete for Section 106 agreements based on the added value that they are able to offer tenants, such as free energy for a period or other much-needed support.

As things stand, the government’s planning reforms, which include the removal of ‘hope value’ for development land, won’t make much difference as it is unlikely developers will voluntarily moderate their expectations when considering bids for Section 106 agreements.

If property developers were forced to sell Section 106 agreements at cost, if this figure couldn’t be agreed upon, an independent body could be appointed to adjudicate, as happens currently with fair rent legislation. Alternatively, local authorities could set the price that registered providers must pay for affordable housing in their Section 106 agreements.

“While the Budget has provided some good news in terms of funding and a commitment to providing a long-term rent settlement, it could have gone so much further”

Elsewhere, the Budget confirmed plans to consult on a new long-term social housing rent settlement. The proposed five-year rent settlement would be welcomed by housing associations and other registered providers as it would bring greater financial certainty. The government’s promise to consult on alternative measures, for example, a 10-year rent settlement, is also welcome as it could provide even greater certainty and enable registered providers to deliver larger, more complex schemes.

A commitment to multi-year funding settlements for local government was a notable omission from the Budget, but it could still get a mention in next year’s Spending Review or earlier, and could drive housebuilding activity further.

While the long-term nature of the proposed social housing rent deal is welcome, the value of it is no more than expected. It is proposed that annual rent increases should be capped at Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) plus 1% for 2025-26, which is well below build cost inflation. Housing associations are already operating on wafer-thin margins and expecting them to snap up development opportunities while being hampered by this restriction on rent increases is unrealistic.

Annual rent increases that track inflation won’t make up for years of underfunding and industry-wide rent caps that have prevented social landlords from investing in the properties they already own.

The housing shortage is at a crisis point and while the Budget has provided some good news in terms of funding and a commitment to providing a long-term rent settlement, it could have gone so much further. Only time will tell if the government recognises that more fundamental changes to the dynamics involved in social housing delivery is needed to address the housing crisis.

Jonathan Cox, partner and head of social housing, Anthony Collins

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters