You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Judith Moran is director of Quaker Social Action, and Ashley Horsey is chief executive at Commonweal Housing

The forgotten generation of unpaid carers need housing and hope

Young adult unpaid carers have specific housing needs that have been overlooked for too long, write Judith Moran and Ashley Horsey

The transition from childhood to adulthood opens a new world of opportunities and independence. It is the period in which we first start thinking about jobs and careers, higher education, moving in with friends and all the excitement that entails.

But today, the riches that were offered to older generations may feel like a pipe dream to many making the transition to adulthood. Locked out of housing, struggling in low-pay job markets, astronomical university fees, rising inflation and cost of living: the youth of today are facing an ever more perilous leap into independence.

And for young adults providing unpaid care, the hurdles are even higher and the track they run even longer.

The latest census revealed there are more than 270,000 carers aged 16-25 in England and Wales. They alone save the country £3.5bn in unpaid care, and the cost to themselves are lower educational attainment and fewer job opportunities. Compared with their non-carer peers, young adult carers are three times as likely not to be in education, employment or training (NEET).

There is also a significant risk of homelessness, as addressed in We Still Care, the powerful new report by Nicola Aylward, head of learning for young people at Learning and Work Institute, which we, Commonweal Housing and Quaker Social Action (QSA), funded and commissioned. The toll of caring for a family member from an early age can understandably lead to tension and a breakdown in family relationships at times, and many young adult carers lack the financial means or social networks to move out of the family home.

“Government at national and local level, child and young people’s services, and housing providers and charities must now all step up, but they must do so in unison”

Despite the positive moves the government has made towards supporting carers, young adult carers are completely absent from policy.

It feels as if young adult carers are forgotten, invisible, wedged in between young carers and adult carers as if they do not have their own distinct needs. Housing is the pertinent one, and without it being addressed, homelessness is a risk for thousands.

In response to the distinct challenges this cohort faces, in 2017, Move on Up was established – an innovative and unique pilot housing project delivered by QSA and enabled by Commonweal. The project combined independent accommodation and specialist, tailored support for young adult carers.

Many young people that came to Move on Up were homeless, while others joined the project after recognising that remaining in their family home was affecting their mental health and life opportunities. Through the provision of accessible and affordable housing away from the family home, Move on Up clients were able to achieve independence and carve out a life of their own, as well as improve ties with their families and their mental health.

The project showed the importance of independent housing and how impactful vital support measures can be. And while this is true, Move on Up’s success is of little reward if young adult carers’ housing needs continue to go under the radar.

Government at national and local level, child and young people’s services, and housing providers and charities must now all step up, but they must do so in unison.

Each sector must take the relevant steps to ensure this group is recognised and identified. For housing providers, this includes ensuring caring responsibilities are identified among residents when assessing housing applications and supporting residents. Alongside this, the housing sector should develop links with local authorities and carer services to create specific referral pathways for young adult carers at risk of homelessness.

While developing these links is vital, evidence indicates local councils are failing to identify the housing needs of young adult carers. Under the Care Act 2014, local authorities have a duty to conduct transition assessments with young adult carers. But housing is absent in the requirements, and previous research from The Children’s Society found local authorities do not always carry out transition assessments, with more than half of young adult carers reporting they had not received one.

“Despite the positive moves the government has made towards supporting carers, young adult carers are completely absent from policy”

To this end, the government should issue guidance to local authorities to ensure transition assessments are routinely conducted and that housing needs are systematically discussed as part of the conversation. This new report is not asking for new provision or new activity, just that the current requirements are implemented properly.

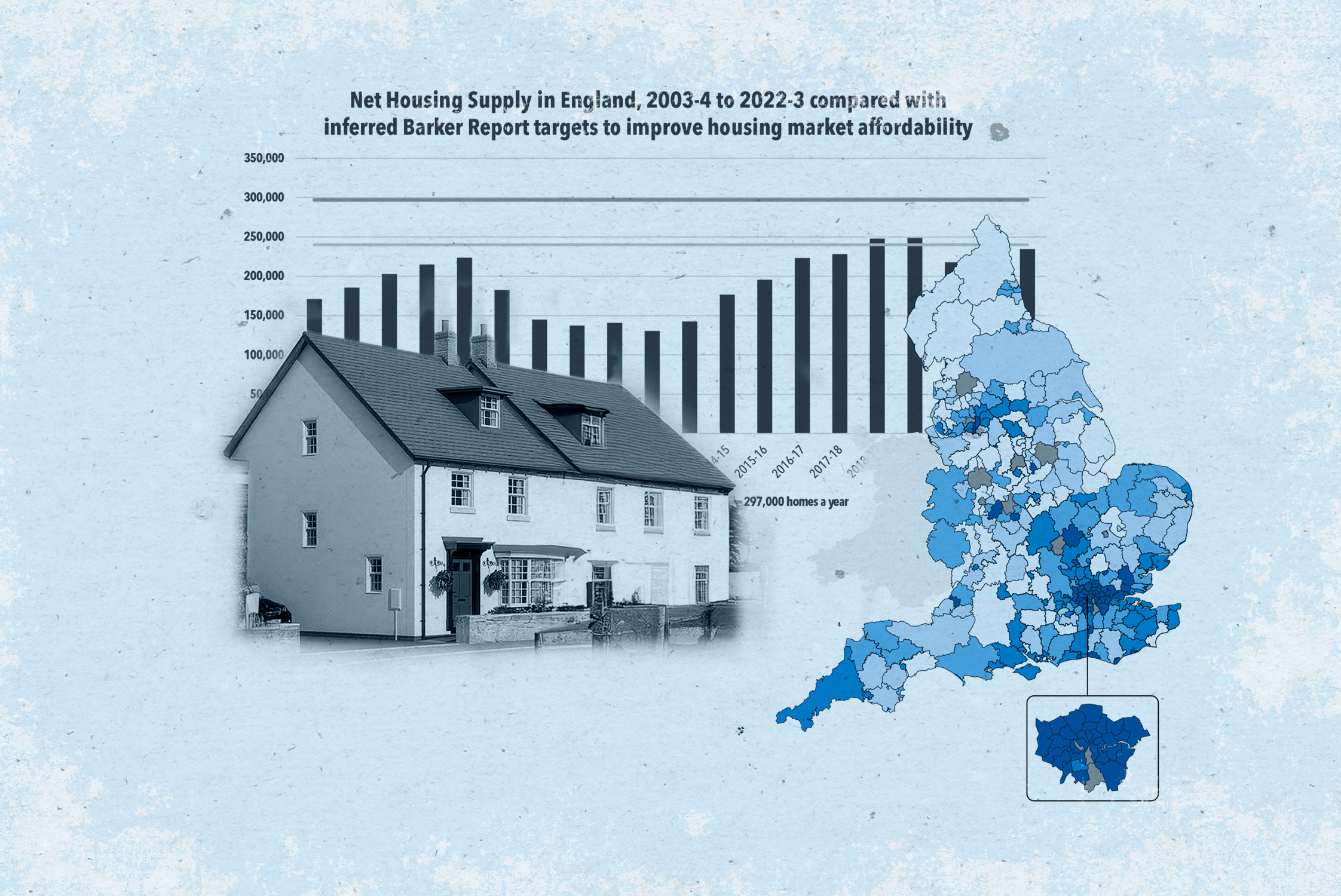

Alongside the direct challenges young adult carers face, the lack of affordable and accessible housing across the private rented sector and long waiting lists for social housing further exacerbate housing barriers.

Young adult carers are not typically a priority group for housing. As such, they can face the same wait as others on housing lists, which can stretch to a decade at some local authorities. To ensure housing needs are no longer overlooked, both local authorities and social housing providers need to classify young adult carers as priority need, because their need is a priority.

At the sharp end of the current crises this country faces are young and hopeful individuals, caring for loved ones without support or salary. It is time we all peeped behind the curtain and brought them centre stage.

Judith Moran, director, Quaker Social Action, and Ashley Horsey, chief executive, Commonweal Housing

UPDATE: 5.6.2023 1pm

This article has been amended to reflect that young adult carers save the country £3.5bn in unpaid care.

Sign up for our care and support bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters