You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Jules Birch

Jules BirchPaying the bill

Jules Birch

Jules BirchBlink and you may have missed it but significant housing legislation you may never have heard of passed its final stages in the Commons on Monday night.

Scant discussion in the housing press (including by me) of the Deregulation Bill is perhaps understandable when you consider that it is huge and it covers everything from the right to buy to outer space*. Several of the clauses involving housing were also not in the original Bill and have been added later.

However, here’s what will become law in England this summer as a result of Monday’s votes (there are other minor changes I don’t have room for):

- The qualifying period for the right to buy will be reduced from five years to three

- Local authorities will no longer be able to impose standards for new homes that go beyond the building regulations (mainly on energy efficiency)

- Legislation banning short-term lets of homes in London will be repealed

- The secretary of state will no longer have the power to require local authorities to produce housing strategies

The last of these may sound more important than it actually is because as I understand it the power has never actually been used but the other three could have major implications and there were last-minute attempts to amend all of them on Monday night.

The right to buy is obviously the big one for social landlords and tenants and the only one that has attracted the most attention. Effectively it restores the qualifying period to what it was before Labour extended it in 2004. Independent analysis for the Bill committee by the University of York found that it could mean extra 700,000 tenants are eligible for the right to buy. However, it found that a maximum of 56,000 of these are in work and earning enough to be able to buy.

Apart from the straightforward implications of those extra numbers – at a time when the right to buy is being abolished in Scotland, remember – the National Housing Federation raised concerns about the impact of the ‘preserved’ right to buy following stock transfer. Receipts are shared with the local authority but it has no obligation to spend them on new homes. It also wanted a reduction in the discount if the sales receipt does not cover debt secured against the property.

The government does seem to have moved on future transfers. The DCLG has published a stock transfer manual and solicitor-general Oliver Heald said on Monday that ‘the intention is that for transfers completing after 30 September 2014, net proceeds from preserved right-to-buy sales are, within three years, to be used to fund new affordable housing at no greater subsidy cost than under the main affordable homes programme’.

However, Green MP Caroline Lucas failed in an attempt to tighten up the rules on replacement homes. Her amendment would have forced ministers to publish a plan to replace homes sold under the right to buy and review the effectiveness of it within a year of the Bill getting Royal Assent. She argued that:

‘Currently, only one in every seven homes sold through right to buy has been replaced, and I find it astonishing that the Government are so complacent that they are not even monitoring the number of homes replaced following the preserved right to buy. Housing associations say that, in fact, the number is likely to be even less than one in seven. It is inexcusable that Ministers have not even consulted housing associations.’

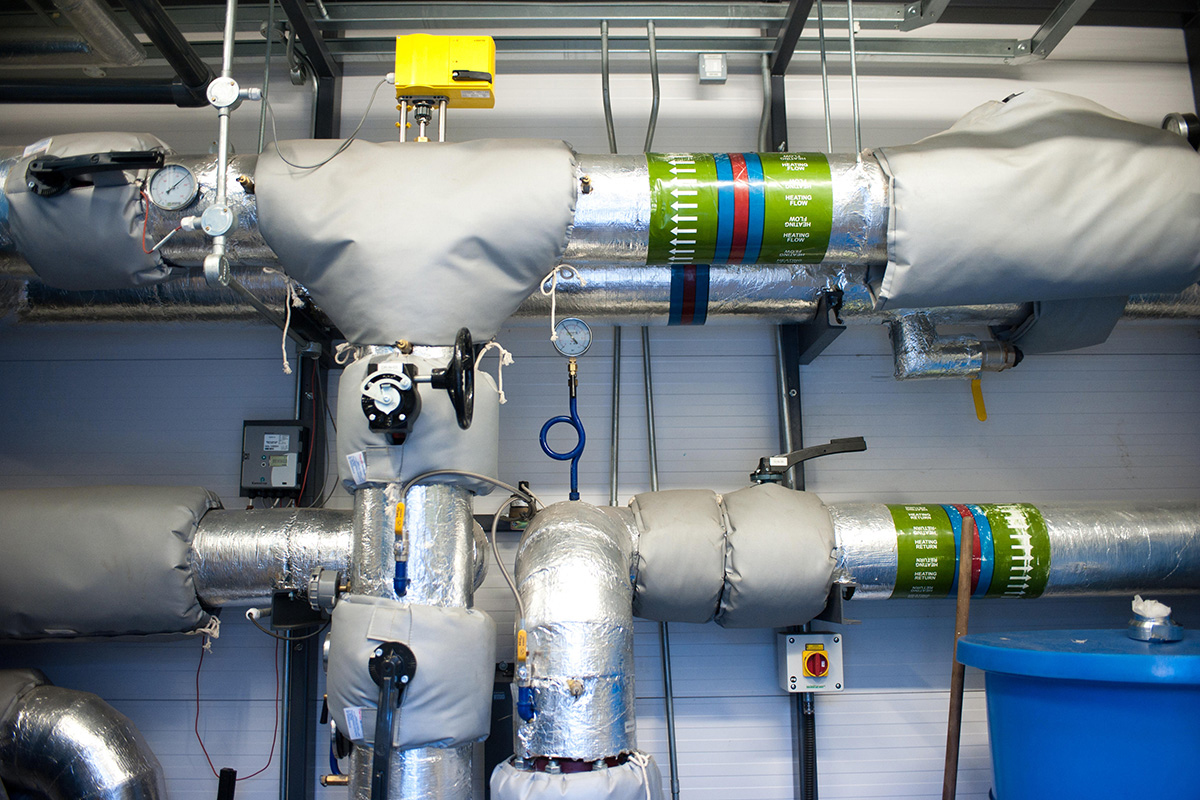

The second produced an unexpected last-minute concession from the government. The Deregulation Bill prevents local authorities from going beyond the building regulations when they set local energy efficiency requirements as part of its more general review of housing standards. As I’ve blogged before, a good case can be made that the government is simply replacing what it sees as ‘red tape’ with blue and yellow tape but this is what it sees as ‘deregulation’.

However, the Bill risked leaving energy efficiency policy in limbo in the run-up to zero carbon homes and in the wake of the abolition of the Code for Sustainable Homes. It would also prevent local authorities that have not already adopted higher energy standards (as in London, for example) from implementing them.

Labour’s Jonathan Reynolds attempted to fix that on Monday with an amendment stipulating that the deregulation ‘shall not come into force until the secretary of state has laid a Zero Carbon Housing Strategy before both Houses of Parliament’. He argued:

‘If the Government are sincere in backing zero-carbon homes, they have nothing to fear from my amendment—it would make no difference to a Government committed to delivering an ambitious zero-carbon homes policy in 2016.’

The amendment was voted down but after the third reading there was an unexpected intervention by Oliver Letwin, the minister for government policy:

‘We are aware that within that framework, the decision on the commencement date for amendments to the Planning and Energy Act 2008, which restrict the ability of local authorities to impose their own special requirements, must be made in such a way that the ending of those abilities to set special requirements knits properly with the start of the operation of standards for zero-carbon homes and allowable solutions. I hope that will make the hon. Gentleman—and, indeed, my hon. Friends who are concerned about the same question of timing—rest easy. ‘

That appears to allow local authorities to continue with their energy efficiency work in the meantime. However, as I’ve blogged before, it remains to be seen how ‘zero carbon’ new homes will really be after 2016 given the influence of developers on the dilution of the standard and an exemption for ‘small’ sites that could amount to a loophole covering a third or more of new homes.

The section of the Bill on short-term lets in London was presented as a classic piece of deregulation by communities secretary Eric Pickles when he announced the change two weeks ago. It would end ‘outdated rules’ from the 1970s preventing London residents from renting out their own homes on a short-term basis without getting planning permission for a change of use. These ‘archaic’ rules caused controversy during the Olympics and are ‘irregularly’ enforced, he said.

However, the measure faced criticism on Monday night from both Labour and Conservative MPs representing Central London constituencies. The worry is that it could lead to a rash of homes being converted into holiday lets. Conservative Mark Field complained that it was being rushed through before consultation was finished. Labour’s Karen Buck said that Kensington and Chelsea, Camden and Islington had all expressed strong reservations ‘precisely because of the fear that they will lead to a loss of residential stock in what are already highly stressed neighbourhoods’.

Oliver Heald said the government was working with London boroughs to try to achieve the right balance between freedom for Londoners and protecting housing supply: ‘We would not want that to be undermined. We are trying to ensure that speculators are not able to buy homes meant for Londoners and rent them permanently as short-term lets.’

However, Mark Field came back later to point out that the rules were introduced in 1973 at a time of acute housing shortage to protect the housing stock from being converted into visitor accommodation. He said the change would have significant implications for London’s stock of permanent accommodation and ‘may make it impossible for our local authorities to meet their targets for new homes’:

‘Above all, it threatens to make central London homes, already traded by many people as some sort of global currency, into little more than assets to be exploited for maximum profit.’

And Karen Buck argued that it would make it much more difficult for local authorities to enforce if they had to prove a property was in ‘habitual short-term use’. She said:

‘No one wants enforcement action to be taken against someone who lets their home for a few days or a couple of weeks, or who does a home swap, but there will be unintended consequences in a high-value, high-turnover and high- pressured area such as central London.’

I wonder if this little-noticed change in a little-noticed bill may turn out to be the most significant in the longer term because of the impact of new technology. Websites like offering short-term lets in major cities are booming around the world and allowing residents to turn their spare rooms into cash by renting them out to tourists by the night. It looks like a brilliant and irresistable use of the internet to bring people together. However, it’s not just rooms that are being let but complete homes.

A quick search of the best known site, Airbnb, reveals thousands of short-term lets available in London for a week from next Saturday. Most of these will of course contravene the existing law, though the lets seem to be happening anyway.

However, as I type this there are currently also 732 complete flats or houses in London available to rent next week. Some could be owners or tenants going on holiday themselves but how many are empty, available to rent to tourists but not to Londoners? And how many more will there be when the law is changed? How many other websites will there be? How many homes will be sub-divided into the smallest rooms possible for short-term lets? Who will pay the bill for deregulation?

* At first I thought the second bit was a joke made by a minister because the Bill has so many different elements but it turns out that it really does cover outer space too in a bit about satellites and liability insurance.