You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Jules Birch

Jules BirchHousing doesn’t seem to matter to ministers

Sooner or later the government will realise the importance of the housing minister job, says Jules Birch

Jules Birch

Jules BirchTheresa May said it herself. Twice. Polling since the election signals it. Housing matters.

Except that it doesn’t really. The delay in naming Alok Sharma as the sixth housing minister in seven years and the fifteenth in this century said it all.

As John Healey tweeted on Monday, if Labour had won, it would already have started creating a new housing department with a minister of cabinet rank.

Instead we are left with Sajid Javid still at the Department for Communities and Local Government despite the apparent determination of Theresa May’s team to move him and a new man taking his Buggins’ turn in the housing job.

“In one sense the lack of priority is understandable… in another it’s mystifying.”

And in place of Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill, the joint chiefs of staff to Theresa May who took the rap for the disastrous Tory campaign and manifesto, we have the ex-housing minister and (thanks to those three) ex-MP Gavin Barwell.

In one sense the lack of priority is understandable.

The Brexit negotiations start next week. The negotiations with the Democratic Unionists continue.

There are goats to be slaughtered so that the Queen’s Speech can be written down (not really).

In another it’s utterly mystifying.

It was noticeable that Ms May mentioned housing twice in her first TV interview about “getting on with the job”.

That seemed to signal housing as a priority and Mr Barwell making his influence felt.

But if that is the case why the big delay in naming the new minister?

Mr Sharma has been MP for Reading West since 2010 and is a former banker and junior minister at the Foreign Office.

From what I can see his track record on housing so far seems confined to voting in favour of welfare reform and changes to council tenancies and saying no to new homes in his constituency again and again and again.

However, I was told on Twitter that he put forward some new ideas on housing that were ignored by Gavin Barwell and George Freeman, the MP who chairs the prime minister’s policy board.

We shall see.

I wrote this blog before the awful fire at Grenfell Tower and the tragic news that at least six people have died.

As Inside Housing is reporting, that raises all sorts of questions about the safety and maintenance of England’s tower blocks.

“If the Conservatives lost this election thanks to a surge in the youth vote, then housing was surely a factor.”

The questions apply not just to actions taken by the landlord and contractors but also to decisions taken (or not) by previous ministers.

And that is only the top of an in-tray that also includes the new funding system for supported housing, the consultation on banning letting agent fees and what to do about the forced sale of council houses.

Another big question is whether he will build on the Housing White Paper with some of the ideas in the Conservative manifesto or whether those disappeared along with Mr Timothy.

But if you forget about the policy for a minute, it’s the politics that I really don’t get.

As I blogged last week, if the Conservatives lost this election thanks to a surge in the youth vote, then housing was surely a factor in that.

The best way to address that was surely to appoint a heavyweight politician of cabinet rank.

After an election that almost all of the pollsters called wrongly, some caution is needed in the interpretation of the results.

There is some evidence that lower turnout by older voters turned off by Tory policies like the dementia tax may also have been a factor.

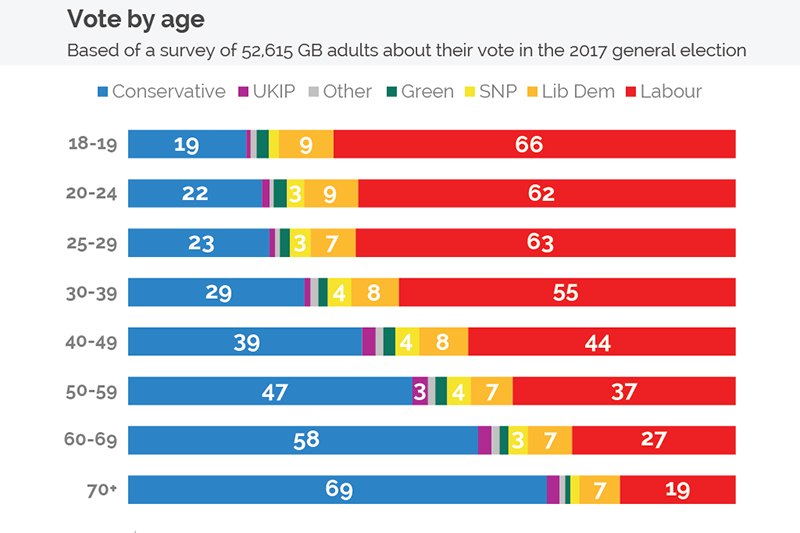

But if you look at YouGov’s poll of 50,000 people on how they voted, what leaps out is Labour’s lead not just among voters most likely to have been attracted by its pledge to scrap tuition fees but among older young people, too:

What should really worry the Conservatives for future elections is that they only ‘won’ on the votes of the over-50s – who are far more likely to vote than younger people.

Turnout among the over-70s was 84% compared to less than 60% among the 18 to 24s.

There could obviously be many reasons for that stark divide in voting by age but different experiences of the financial crisis and austerity could well be one, with housing an important factor.

After all, most people old enough to have bought a house 15 to 20 years ago – before prices really went out of control – will now be aged 45 to 50 and will have seen their mortgage costs fall as a result of low interest rates since 2008.

Younger people, by contrast, will have either stretched themselves to the limit to buy at unaffordable house prices, or be stuck in an unreformed private rented sector, or have waited years for social housing.

David Cameron and George Osborne perceived the political importance of housing.

They clearly saw the promotion of homeownership as the same thing as the promotion of voting Conservative and, according to Nick Clegg, they refused to invest in social housing because it would “create Labour voters”.

Under Theresa May and Gavin Barwell the Tories have rowed back on the obsession with ownership and have belatedly realised the need to do more to help private tenants, but those voting figures suggest it’s not nearly enough.

Does it matter who is the housing minister?

Maybe not when so much power rests with the chancellor and work and pensions secretary, but the job is now much bigger than it once was. And that was before the awful events overnight.

Every year or so the revolving door at Marsham Street swings round and a new housing minister steps through.

Sooner or later the government will realise the importance of the job socially, economically and politically. But clearly not yet.