The heat network bills crisis: how residents are affected and what can be done to help

Residents on older heat networks are still facing rising bills from the price shock of the war in Ukraine. James Riding investigates how they are being affected, and what more social landlords – and new regulations – can do to protect residents from escalating bills

Will Damazer’s leasehold flat in Southwark, south London, is connected to a communal boiler installed in the early 1960s. In the past two years, his heating and hot water bill shot up from £1,105 to £2,371. The shock led him to become a researcher and campaigner for heat network customers’ rights.

“I have a family friend, they’re a social housing tenant. They said, ‘Maybe I should move out, I can’t do this every year,’” he says. “It’s quite sad to think there are people who are pushed into that.”

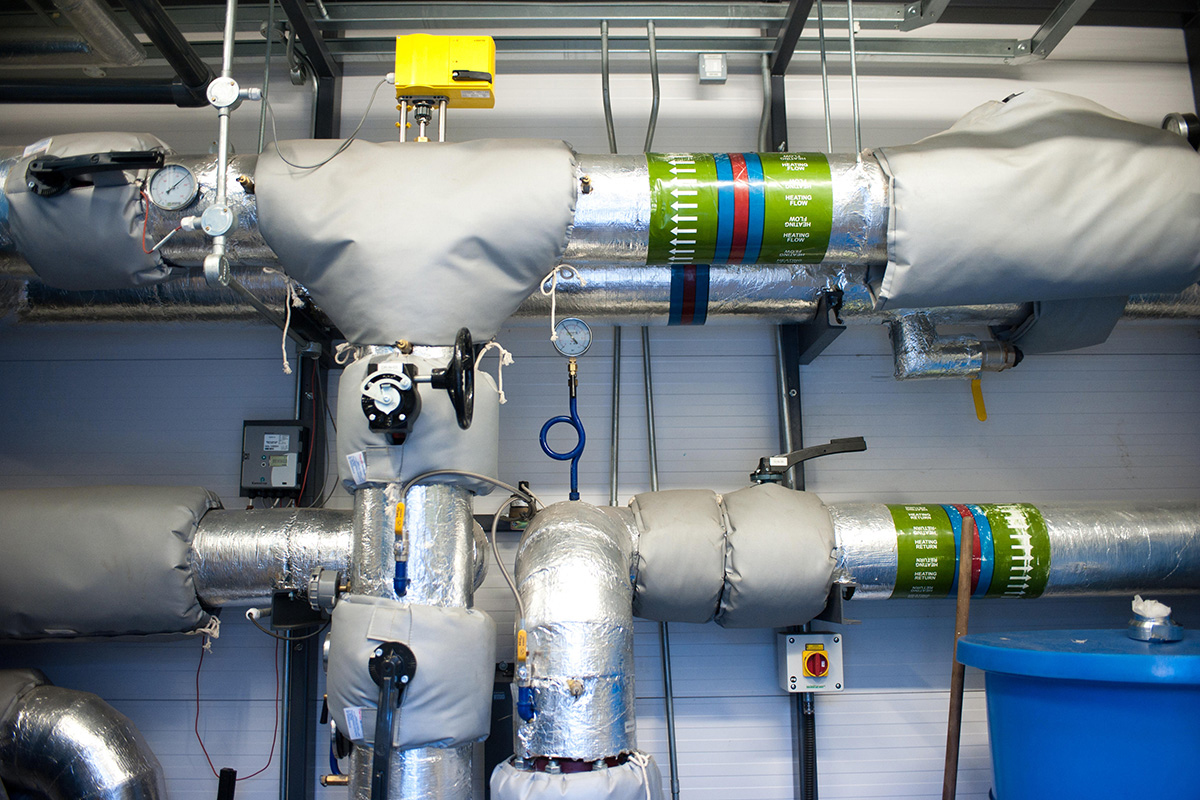

Heat networks carry heat from a central source to multiple homes. Newer networks tend to be powered by a big heat pump; the older kind, built during the council-led construction boom of the 1960s and ’70s, often uses a gas-powered communal boiler.

It is a growing sector – last month, the government announced six “heat network zones” in major English cities, with plans for a £1bn network in Westminster. But as the case for new heat networks builds, some residents connected to older networks are reporting sharp rises in their bills.

Energy prices are down since the initial spike of the energy crisis when Russia invaded Ukraine. But questions about the fairness of heat network pricing did not go away – particularly for older networks, which don’t have individual meters, rely mostly on gas, and may have leaky pipes and inefficient, older boilers. Ofgem is poised to intervene – with new regulations of heat networks being deliberated (see box).

So what are the challenges facing heat networks? How extreme have price rises been? And have social landlords made the most of government funding meant to protect residents from rising costs?

Mr Damazer wrote a report for the Social Market Foundation thinktank, which found that 900,000 UK households, or one in 25, are part of a heat network, rising to one in 12 in social housing. His research found that 57% of heat networks are not metered, rising to 85% in the social rented sector, so residents are billed a flat charge regardless of how much they use their heating.

Unlike retail customers, heat network residents did not benefit from the government’s 2022 energy price guarantee, because councils buy their energy on the commercial market.

Six months after the energy price guarantee came in for retail customers, the government made funding available to subsidise heat network customers’ bills and upgrade old heat networks. The Energy Bills Discount Scheme (EBDS) ran from April 2023 to April 2024 to give landlords a discount if their energy contracts were over a certain price. Meanwhile, the Heat Network Efficiency Scheme (HNES) has distributed over £30m since it was launched in 2023 to improve 190 existing networks.

Inside Housing sent Freedom of Information requests to all councils in the country. We asked for the amount charged to them by their energy supplier for energy on their residential heat networks in the past four years. We also asked if they had applied for the two government schemes – the EBDS and the HNES. We found gigantic rises in energy bills facing councils and their heat network customers. And we also found that many councils have not applied for these pots of money to offset the costs.

Retail gas bills are around 29% higher in 2024 than in 2021-22, according to the House of Commons Library. By contrast, councils have seen energy bills surge much higher (see table).

Stephen Knight, chief executive of Heat Trust, a consumer protection scheme for heat network customers, says: “Landlords haven’t been able to play the market. I don’t think your typical landlord is an expert in energy procurement.”

While some of the increase is down to adding new homes to the network, adjusting for this, the increases are significant. Wigan Council saw a rise of 301%, adjusted for new homes added. In most cases, these surging prices were a hangover from the 2022 energy price spike, which had been delayed because the councils bought energy for their heat networks in advance.

Stephanie Noyce is head of money and digital inclusion at Clarion Futures, and works on the housing association’s fuel poverty strategy, including its 180 heat networks. Clarion negotiated a three-year energy contract in 2021, which she says saved £54m for residents on heat networks. “When you look at it in that way, there is massive potential,” she says, although “we’re a big buyer”. When that contract ended, she says, Clarion has only bought energy for one year, because it is predicting that prices will come down.

Most of Clarion’s heat network homes have household meters and the landlord works with residents to assess their needs. As a result, she says, Clarion should be well prepared for the forthcoming regulation. “You might protect [residents] for the next two years, and then there will be a catch-up when that price is renegotiated,” she says. “I don’t know how we smooth that.”

The 10 councils with the largest increases in heat network costs

Source: Inside Housing research

Notes: Kensington and Chelsea, Cambridge, Newcastle and Wigan added new homes to their heat networks during the four-year period. Wigan provided a like-for-like figure, used here. Kensington and Chelsea said it connected 83 new homes to its heat networks over four years. Cambridge said £80,260.43 of its figure in 2023-24 covered electricity for newly developed heat networks

Rising costs

Inside Housing approached all 10 councils with the biggest cost increases, and their energy suppliers, for comment.

Cambridge City Council saw its total bill for seven sites rise by £98,869 or £14,124 per site. It procures its energy through the Eastern Shires Purchasing Organisation, which represents a large group of public bodies and makes multiple trades over a 12 to 18-month period to manage risk. Pawel Goc, energy manager at Cambridge City Council, told Inside Housing that the council has secured gas prices for 2024-25 that are down 20% on the previous year.

A Kensington and Chelsea spokesperson pointed us to a study which found that out of 404 public bodies (in general, not just on heat networks), 74 had higher electricity costs than the council and 239 had higher gas costs in 2023-24. Kensington and Chelsea uses Crown Commercial Service as its energy broker, which also buys energy for central government and NHS trusts.

Kensington and Chelsea and some of the other councils told us what action they have taken to mitigate bill rises for residents. Kensington and Chelsea successfully applied for the EBDS and has a tenant sustainment fund to support residents who are struggling financially.

Newcastle City Council currently subsidises the charge to residents for their heating.

Ealing Council’s utility provider has installed advanced meters to “provide even more precise data to inform future charge adjustments”, according to a spokesperson.

The increases were harder to mitigate for some than others. Cambridge, for example, may have seen bills rise by 350% in four years, but the rise in absolute terms is £179,130 – much less cost for the council to absorb than Southwark’s 199% rise, which amounts to £14.7m.

A spokesperson for Croydon Council says: “The council continues to work to provide the most economical energy deal for residents on heat networks. We secure all gas supplies through a public sector buying consortium.”

Bolsover District Council says it has only increased energy bills by the same Consumer Price Index as rent charges, rather than the percentage increase. In 2023, it entered a four-year agreement with Crown Commercial Service.

When is heat network regulation starting?

Ofgem was named the regulator for heat networks in 2023. Two consultations on regulatory oversight and consumer protections were launched in November and will close on 31 January 2025. Providers will be required to provide more transparency on pricing, and Ofgem is looking at cost benchmarking. There is a plan to introduce a register of customers in greatest need, and heat providers will have to provide data on unplanned interruptions to heating and hot water.

Only one in five (or 18 councils) told us they have already installed meters to every household on their heat networks. But this is likely to change. Household meters have been required on all new heat networks since 2014 and forthcoming regulations are likely to require more to be installed in older properties.

An Ofgem spokesperson says: “Heat networks will play a key role in delivering the government’s net zero ambitions. We are working with them to design a regulatory regime that will deliver protections for all consumers, and support government ambitions to attract investment and accelerate the deployment of reliable, decarbonised heating and cooling networks.”

Mr Damazer told us he feared that not all councils applied for the support that was available.

Inside Housing asked all UK councils if they had applied for the EBDS and the HNES. Of those heat network-owning councils that replied, just two-thirds (67%) had applied for the EBDS. It was a legal requirement for heat network providers to do so. However, Ofgem says it does not have the power to issue retrospective fines to councils as it was not responsible for compliance with the schemes.

Of the 10 councils with the highest energy price spikes, only High Peak did not apply to the EBDS; it did not respond when we asked why. The scheme has now closed.

Many older heat networks run on inefficient pipes. Mr Damazer worries cash-strapped councils will pass on the cost of underinvestment to residents through major works projects.

Mr Knight says some heat networks built in the past 10 years have issues with inefficiency and overheating. “Up until three years ago, when the commercial energy prices went through the roof, [builders] could get away with building inefficient systems because commercial gas was so cheap,” he says. “We’re now in a world where commercial gas is three times what it used to be.”

Just one in three councils applied for the HNES to update their heat networks.

Nicholas Doyle, a director of heat network advisory firm Chirpy Heat, says the EBDS was not well promoted by the government. He says “they were relying on residents to raise it” with their council.

Inside Housing’s numbers show that take-up was “very low” and that “there is a backlog of people who were due support who haven’t received it”, says Mr Doyle. “That’s money that is due to them, and that needs to

be passed on to them.”

Update: at 2:15pm, 08/01/25

This article was updated to clarify that Ofgem was not responsible for compliance with the EBDS and HNES, so it is unable to issue fines retrospectively to councils that did not apply.

Recent longform articles by James Riding

Dagenham fire: what happened and what we know about the building

A fire at a block of flats in Dagenham, east London, on Monday has sparked fresh debate about the slow progress of cladding remediation in the UK. James Riding runs through what we know so far

Peter Denton discusses the Homes England review and Section 106 jitters

Homes England’s chief executive tells James Riding that a new government review is a “call to arms” for the agency to take a more hands-on role in development

The man who runs Homes England’s Affordable Homes Programme

Shahi Islam speaks to James Riding about his new role as director of Homes England’s Affordable Homes Programme and his desire to be “more front-facing” in the sector

Sign up to our Best of In-Depth newsletter

We have recently relaunched our weekly Long Read newsletter as Best of In-Depth. The idea is to bring you a shorter selection of the very best analysis and comment we are publishing each week.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.