Jules Birch

Jules BirchRonan Point 50 years on: the worrying legacy of a disaster

Fifty years on from what was once the worst disaster in social housing, Jules Birch looks at the legacy of Ronan Point and what we can learn from it

Throughout this week we will be publishing a number of articles on building safety to mark the 50th anniversary of the Ronan Point disaster

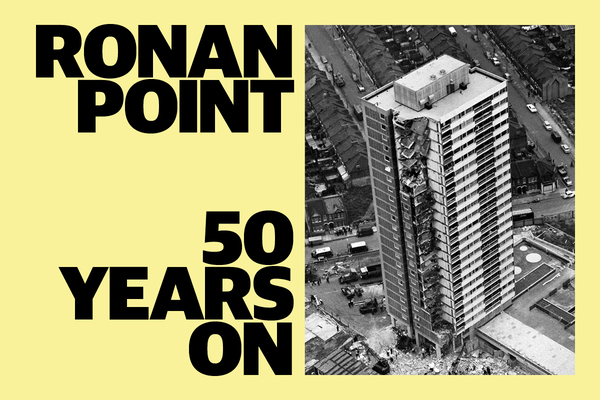

This week marks the 50th anniversary of what was, until recently, seen as the biggest disaster in the history of council housing.

At 5.45am on May 16 1968, a cake decorator called Ivy Hodge put the kettle on for a cup of tea.

A gas explosion triggered by a faulty connection to her cooker blew out the walls to her flat and triggered the progressive collapse of one corner of the 22-storey Ronan Point tower block in Newham in east London.

“A public inquiry quickly established fundamental flaws in the large panel, system-built design.”

Four tenants were killed and several more had miraculous escapes, but the fact that the explosion happened so early in the morning prevented an even worse disaster – most people were still asleep in the relative safety of their bedrooms rather than exposed to the collapse in their kitchens.

That aside, the most shocking thing about the disaster was that it happened in a new building and the first tenants had moved in two months before.

A public inquiry quickly established not just the fault in the gas connection, but fundamental flaws in the large panel, system-built design. The collapse could have been triggered not just by an explosion but also by high winds and fire.

That led to reform of the rules on gas safety and a shake-up of building regulations to ensure that the structure of tall buildings became more robust.

Over the years, Ronan Point came to be seen as the high water mark of both council housing and modernist architecture.

As time went on, the blame was increasingly laid at the door of architects, local authorities and even the whole idea of council housing.

“The construction of tower blocks was encouraged by central government ministers of both parties.”

It’s certainly true that some designs were flawed and untested, and some councillors arrogant, self-aggrandising and even corrupt.

But some important factors are edited out of that account.

First, the construction of tower blocks was encouraged by central government ministers of both parties.

Conservative and Labour governments alike focused relentlessly on increasing the supply of homes – for understandable reasons.

As John Grindrod points out in Concretopia, Newham had built almost 15,000 new homes by 1968, a post-war record for a London borough, but there were still 9,000 slums to be cleared in the area.

Tower blocks were heavily incentivised by central government.

The Tory 1956 Housing Subsidies Act, for example, incentivised tower blocks by paying progressively higher subsidies for buildings over six, 15 and 20 storeys.

Second, most of the large panel system (LPS) blocks like Ronan Point were built by big construction companies using systems licensed from continental Europe.

Industrialised building methods offered the prospect of delivering homes more quickly without being constrained by skills shortages in conventional building trades.

“The disaster shook but did not break confidence in tower blocks, and they continued to be built in large numbers.”

That handed those firms enormous power, and contracts were often awarded with limited or no competition and with minimal design input.

The system used on Ronan Point and its sister blocks, for example, was developed in Denmark but had only been used before on buildings up to six storeys.

Third, the disaster shook but did not break confidence in tower blocks, and they continued to be built in large numbers, including the robustly designed Grenfell Tower in west London (designed in 1967 and completed in 1974).

And, as John Boughton points out in his excellent new book Municipal Dreams (an extract of which you can read here), even in 1968 the emphasis had already begun to shift to lower-rise development and rehabilitation, with the premium for flats above six storeys abolished two years earlier.

For all the part it played in the rejection of the mass housing model, Mr Boughton points out that “with lessons learnt and aspirations honed and tempered, the decade that followed would see the construction of some of the finest council housing ever built. Sadly, that in the end would prove to be its swansong”.

Following the inquiry, Ronan Point was rebuilt and strengthened, and tenants moved back into their homes in 1973.

Watch footage from the aftermath of Ronan Point:

But tenants and other campaigners continued to warn that LPS blocks were fundamentally unsafe, and shoddy building work meant that significant defects quickly emerged.

By the 1980s tenants at Ronan Point were reporting that they could smell food being cooked 20 storeys below them and hear people’s conversations in flats above and below them. Finally, the decision was made to demolish it and similar blocks.

After Ronan Point was taken down and inspected floor by floor, tests found that the building still had a weak structure that would have collapsed in a fire, high wind or explosion.

Newspapers and drinks cans were found in the joints between the panels rather than concrete.

At first glance the two disasters seem very different: Ronan Point was a newly built LPS block that suffered a partial collapse after an explosion, whereas Grenfell Tower was a newly refurbished, non-system block that suffered a devastating fire.

One became seen as a symbol of the failures of council housing, the other as a symbol of the way that poor people are treated in the richest part of the country.

But look a little deeper and the parallels become all too clear. The Grenfell inquiry is taking much longer than the one for Ronan Point, but it would be surprising if it did not highlight a whole series of common factors.

In the aftermath of both, it was clear that warnings were not heeded: partial collapses of other buildings’ windows being blown in on tower blocks in the case of Ronan Point; and a series of other fires, most notably at Lakanal House, in the case of Grenfell.

Both highlighted concerns about the way building projects are procured and carried out, how the quality of the work is checked and the adequacy of the building regulations.

“Perhaps the most worrying legacy of Ronan Point is that the story did not end when it was finally demolished in 1986.”

Both showed the dangers of not listening to tenants. As Frances Clarke put it in a piece for Inside Housing just after the Grenfell fire, how was it that we did not learn from the experience of Ronan Point, where shoddy workmanship meant that flats designed to withstand fire for an hour only lasted 11 minutes?

Both led to big problems for landlords rushing to make their homes safe: in 1969 the Greater London Council faced a financial crisis as a result of the £3m bill for strengthening its blocks; in 2018 the problems are spread across council, housing association and private landlords, and affect tenants and leaseholders alike.

And both point to the way that a focus on targets and cost savings and reliance on private contractors to deliver them can be a recipe for cutting corners on safety.

The pay of the largely unskilled workforce assembling Ronan Point’s panels onsite depended on the speed at which they built.

But perhaps the most worrying legacy of Ronan Point is that the story did not end when it was finally demolished in 1986.

The disaster did lead to an immediate overhaul of Part A of the building regulations to ensure that the design of tall buildings was sufficiently robust.

But in the wake of Grenfell, safety checks on LPS blocks revealed some where the strengthening work had never been carried out and the gas supply had not been disconnected.

It was a shocking reminder of the way that the balance between safety and cost can slowly tilt back following a disaster.

As the debate about combustibility, desktop studies and prescription in Part B of building regulations continues, we would do well to remember that.

Jules Birch, award-winning blogger

Ronan Point: 50 years on

We have published a series of articles to mark the 50th anniversary of Ronan Point:

Are tenants being listened to on building safety? Tower block safety campaigner Frances Clarke questions whether Dame Judith Hackitt is really listening to tenants

The tower blocks that time forgot Fifty years ago councils were told to assess high-rise buildings that were similar to Ronan Point and strengthen them where necessary. So why are problems with some of the blocks still emerging?

One man’s 50-year battle to improve tower block safety Meet architect Sam Webb, who has been campaigning on safety in tower blocks since the disaster at Ronan Point

The worrying legacy of a disaster Jules Birch reflects on what we can learn from the Ronan Point disaster

Watch a new film about Ronan Point Filmmaker Ricky Chambers, whose grandparents and mother lived in Ronan Point, has made a film telling people’s stories of the ill-fated block. Watch the film and read Mr Chambers’ comments on why he made it

The dangers of large panel system construction Building safety expert Sam Webb explains why the system of construction used at Ronan Point was flawed, and how it was used in other buildings still occupied today

The Hackitt Review

Photo: Tom Pilston/Eyevine

Dame Judith Hackitt’s (above) interim report on building safety, released in December 2017, was scathing about some of the industry’s practices.

Although the full report is not due to be published until later this year, the former Health and Safety Executive chair has already highlighted a culture of cost-cutting and is likely to call for a radical overhaul of current regulations in an interim report.

Dame Hackitt’s key recommendations and conclusions include:

- A call for the simplification of building regulations and guidelines to prevent misapplication

- Clarification of roles and responsibilities in the construction industry

- Giving those who commission, design and construct buildings primary responsibility that they are fit for purpose

- Greater scope for residents to raise concerns

- A formal accreditation system for anyone involved in fire prevention on high-rise blocks

- A stronger enforcement regime backed up with powerful sanctions

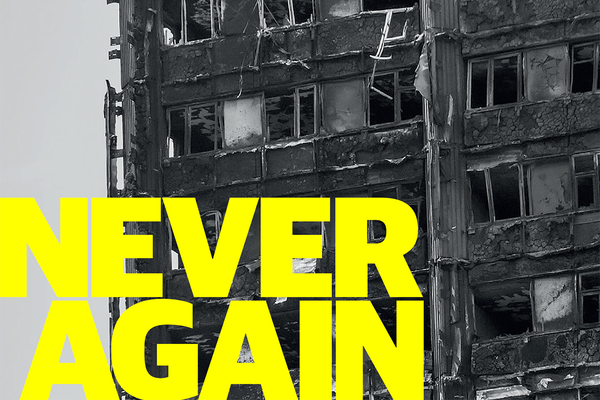

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.