How can the sector do more with less?

The government has asked social landlords to build more new homes, while juggling myriad competing pressures. Inside Housing pulled together a group of experts to share ideas on the best way forward. Photography by Jonathan Goldberg

In association with:

![]()

Housing sector leaders today are under unprecedented pressure. They are juggling a complex business environment – facing everything from rising costs to increased demands from government, to an economy which puts their customers at risk – and they are doing it at a time when the risks of getting it wrong are higher than ever before.

The sector is under close scrutiny from the government, public and media, putting landlords and their leaders in the spotlight. New regulatory regimes mean new compliance requirements, too. The Building Safety Regulator and the newly revised consumer standards have added new layers of complexity and raised expectations.

The government’s focus on building more social housing means there is pressure on the sector to help it deliver its promises to the electorate, as well as play its part in the drive towards decarbonisation as we hurtle towards the 2050 net zero deadline.

In short, housing providers are, once again, being asked to do even more with less – a familiar paradigm, perhaps, but nevertheless apposite today. How can landlords meet these competing demands, and what role will technology play in helping them to do it?

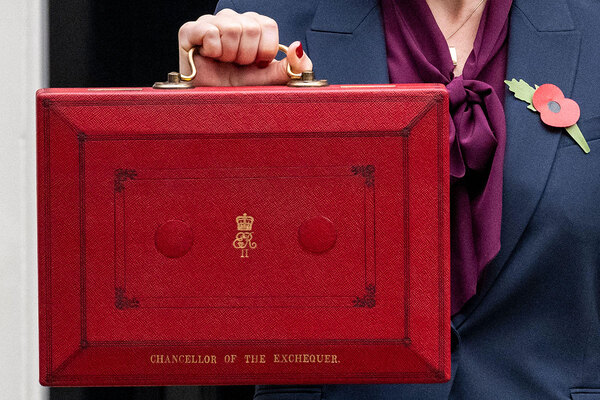

Before the Budget in October, in association with strategic delivery consultancy Newton, Inside Housing brought together a panel of sector leaders to discuss these issues and share their expertise.

Weight of responsibility

“We have realised for a while that we don’t think we can continue to do more for less. There has to be an open and honest conversation about what the roles and responsibilities of housing associations are,” says Danny Thorpe, director of communications and external affairs at social landlord Clarion. “Austerity has impacted not just people, but obviously all organisations as well. And that needs to be recognised.”

Economic and social pressures are having a worsening impact on vulnerable residents, and “our staff are being asked, potentially, to conduct mental health capacity assessments”, Mr Thorpe adds. “We’re just not in a position to do those things – and certainly not to do them well. So I hope that, alongside a long-term rent settlement in the Budget, there will also be a significant investment in basic public services.”

For Ian Wardle, chief executive at A2Dominion, one answer may lie in building better partnerships with other organisations, and with residents. A2Dominion’s resident base has changed in recent years, he says. “It is [now] the most marginalised, who have been on waiting lists for a significant period of time and who need a lot of help and support,” Mr Wardle explains. “That puts huge pressure on households and on our teams.”

He believes that partnership working in the housing sector is “massively underdeveloped” and could help to relieve some of that pressure on individual landlords and councils. “Why don’t we share some of our services [with local authorities]? We do some of the same things,” Mr Wardle says.

There is scope, too, in freeing staff from having to work in the same way they always have done. “I’m interested in how we can help colleagues find solutions for themselves and feel more supported, because it is a really hard job and it has changed massively.”

Prevention is better than cure

One way to squeeze more from existing resources could be to identify areas where a large amount of money is being spent to little effect. Temporary accommodation is one such problem, says Ian Davis, chief executive of Enfield Council.

“What we’ve seen [in London] is more and more money going into paying for expensive [temporary] accommodation – a very bad use of the public purse,” he says. “It means less money being invested upstream into those universal services, into those targeted interventions. So I’m really hopeful that after [the Autumn Budget], there’s money – not just for the accommodation, but for investing in good upstream services that focus on the most vulnerable people.”

Another factor adding to the pressures on the sector is the shortfall in recruitment into housing. “Trying to bring people in at all levels is really tough,” says Mr Davis. “We’re all competing against each other.”

He says there is still a lingering perception that roles in housing and the construction industries are not high-quality jobs. “Actually they are fantastic jobs: sustainable, good employment, good salaries. We really need to work together to try and get that pipeline moving. So how do we work with schools? How do we work with colleges?” he asks.

Landlords need to focus on making a housing career more appealing to the younger generation, agrees Gurpreet Dhillon, HR business partner at Anchor. “It’s not just about this year – it’s looking five years ahead. A lot of useful discussions come out of that.” She praised the University of Reading for its programmes to boost student social mobility, and suggested tapping into similar projects at other institutions. “How can we sponsor those programmes to get some of those students working with us, either as placements or sponsorship programmes, and get leaders out there to talk at some of these events?” she asks.

In 2022, Southern Housing Group merged with Optivo. The two years of integration since then have presented an opportunity to look at business operations, says Tom Paul, executive director of strategy and change at the resulting 80,000-home organisation, Southern Housing. “We haven’t done too much reinventing the wheel,” he says. “Unless a programme comes to an end, and then it’s the time to think, ‘Well, what should that wheel be?’”

Mr Paul challenges the premise of our discussion topic. “Certainly in our case, we do have more [resources],” he says. “It’s just that there’s even more that we need to do.”

The question is where organisations should invest to make the greatest difference. For Southern, the answer is clear. “Our focus is on our repairs service,” says Mr Paul. “It’s the number-one driver of satisfaction, the number-one source of complaints, and it’s our number-one cost. We believe that a repairs service which will deliver for residents will also be more cost-effective.”

Eliminating slack in one part of a system – repairs and maintenance, for example – can free up resources elsewhere. Shyam Radia, a director at Newton, says a common problem in repairs is failure to collect the right information at the start of the process, forcing teams to make more than one visit to a resident to manage a repair. “Then you get more demand in your contact centre, because everyone is picking up the phone to ask what’s happened with their repair,” Mr Radia says.

But fixing these problems has to start with residents. “The key thing is the customer journey. That needs to come first, with everything else designed beneath that to make sure that happens.”

Delivering services

Organisations can also spend time evaluating whether their services are already delivering best value, both for the business and its customers. This process led A2Dominion to take what Mr Wardle describes as the “really difficult decision” to exit the care sector altogether.

“The group was only subsidising [our care service] with £1m a year, but what informed that decision was the time and effort to maintain care and support services when there are others in the market that could probably do it better than us,” he says. “We might be able to run certain lines of business, but are we well placed to do it? Is it adding value to our housing objectives, and is it adding value to our customers?”

L&Q made some similar choices, explains Steve Moseley, executive group director of governance and transformation at the London landlord. “We have exited some areas, and in a lot of cases, we’ve sold that to local councils as well, because we recognise that they’re best-placed to deliver [those services],” he says. “It’s about your operating model: what looks best? And where can you leverage scale… and when is having a more local approach important?”

Mr Radia says he is having similar conversations with other organisations in the housing sector. Complying with the new regulatory regimes has led to “a lot of extra teams, processes or people”, he says – and again, the solution begins with the people the sector exists to serve. “To start, everything must be hung off the resident journey, and what you need to do to fulfil that journey,” Mr Radia says. “What teams do you need? What processes do you need? How can you make it as simple as it needs to be, while remaining performance-focused?”

Nascent digital tools such as AI and big data can also help to generate efficiencies for landlords and to improve the lives of their residents. But, warns Pam Smith, chief executive of Newcastle City Council, this has to begin with the customer journey. “AI can help to intelligently analyse that customer journey,” she says. It can help staff understand when and where best to help a customer, and when that can be automated.

‘‘So where you need that human interaction, let’s make it really quality human interaction. And where we don’t, let’s have quality AI doing it,” Ms Smith says. “I think we need to adopt some of this private sector technology and not be afraid of it.” Housing providers can also use big data to “look forensically at our neighbourhoods”, she says. “Where are the issues, and where is it absolutely necessary to make interventions?”

Combining big data and AI with the resident voice could unlock significant efficiencies in asset management programmes, too. “Instead of programmes where we replace a kitchen every so many years, I think we ought to be tailoring our asset management to individual circumstances,” Ms Smith says. “A family of five or six is going to put more wear-and-tear on an asset than somebody living on their own. So we need to start using who’s behind the front door, and their knowledge and experience, along with the data, to provide a more intelligent and holistic approach to asset management.”

Technology could also be of indirect help in solving the recruitment crisis, Mr Radia argues. “The feedback I keep hearing is around people wanting to be involved in the innovation, the excitement. This is where you’ll get the younger generation involved,” he says. “If we can get housing to talk about AI, about technology, about some of those more exciting [areas], that’s really going to start to bring some of those people through.”

More generally, there is a risk of a “buzzword soup”, says Mr Paul. He flags the need for direction. “With any technology, we have to be focused on where our challenges are,” he says. “Yes, AI can help with diagnostics, with scheduling, but our job has to be about focusing on the areas which really matter for our residents, and matter in terms of driving up performance and driving down costs.”

Participants

Martin Hilditch (chair)

Editor, Inside Housing

Ian Davis

Chief executive, Enfield Council

Gurpreet Dhillon

HR business partner, Anchor

Steve Moseley

Executive group director of governance and transformation, L&Q

Tom Paul

Executive director of strategy and change, Southern Housing

Shyam Radia

Director, Newton

Pam Smith

Chief executive, Newcastle City Council

Danny Thorpe

Director of communications and external affairs, Clarion

Ian Wardle

Chief executive, A2Dominion