Senior government official was warned of ‘grave concerns’ about Grenfell-style cladding in 2016

A senior government official was warned of “grave concerns” over the widespread use of the cladding material used on Grenfell Tower by a senior industry figure 15 months before the deadly fire, new emails released by the inquiry have revealed.

The inquiry also showed video footage of an industry conference in January 2016 where the material was described as a “time bomb” and it was warned that “an exact repeat” of huge cladding fires in Dubai could happen “in any number of buildings” in London.

Despite being aware of these warnings, the National House Building Council (NHBC) issued industry guidance months later which said the use of the highly combustible polyethylene-cored aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding in high rises was acceptable.

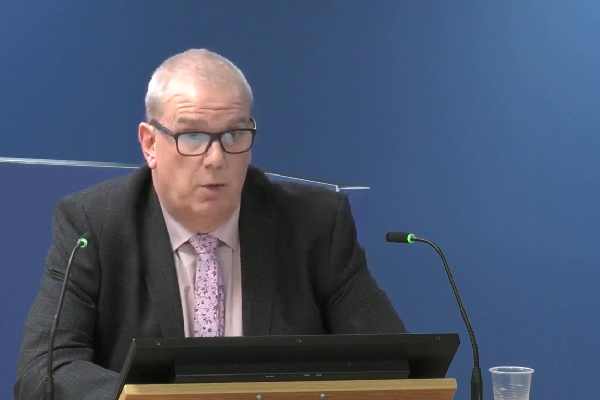

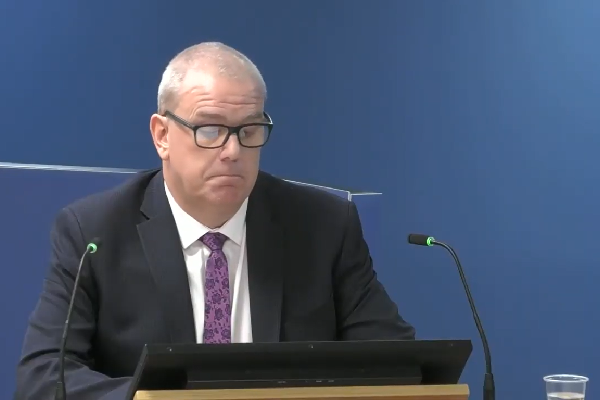

A senior manager at the NHBC – which is the country’s largest building control inspector and warranty provider – today denied that the guidance was “a desperate attempt” to retrospectively justify buildings it had signed off with the highly flammable material.

ACM was ultimately used on Grenfell Tower and has been identified as the “primary cause” of the devastating external fire spread on the night of the blaze in 2017. Experts have compared its combustibility with solid petrol and by 2016 it had been involved in a range of huge fires worldwide, particularly in the Middle East.

Today’s revelations began with a seven-minute video from a conference held in January 2016, hosted by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) and fire barrier manufacturer Siderise, covering the issue of dangerous facades.

The footage showed Nick Jenkins, a senior figure at cladding firm Euroclad and Booth Muirie, asking a question about the acceptability of ACM under English building guidance Approved Document B.

He said when the material has a polyethylene core “it burns very aggressively”, but that this material still obtained a ‘Class 0’ fire rating which was apparently the standard required by the official guidance.

He said that he was only aware of two projects in the UK that had used a less flammable version of the cladding.

Calling for the product to be banned, he went on to warn that “you could have an exact repeat of the Dubai fire in any number of buildings that we supply product to in London”.

The question prompted the chair to ask the panel if “we are sitting on a time bomb as well in terms of some of the materials that are installed”.

Steve Evans, head of technical operations at NHBC, was one of the panellists, having just given a presentation on the ‘routes to compliance’ for combustible materials on tall buildings.

He was recorded responding to the question about a “time bomb” by saying “you will have to ask our builder customers” to scattered laughs.

He added: “There is an anomaly in the approved documents… so there could be instances where you have this polyethylene-filled panel on buildings over 18 metres.

“We have highlighted this to DCLG [the government department responsible for building regulations] and they are looking at Part B [the regulations covering fire safety] at the moment.”

This contrasted with evidence he gave to the inquiry today where he said he believed the use of polyethylene-cored cladding panels was banned by the wording in Approved Document B which said “filler materials” had to meet the higher fire standard of ‘limited combustibility’.

“When you responded, why didn’t you just tell the audience straight up that as evidenced by the Dubai cladding fires ACM panels with a PE core were dangerous and non compliant and should not be used and should never have been used?” asked Richard Millett QC, lead counsel to the inquiry.

“It is probably a badly worded answer,” Mr Evans said. “I thought I was trying to explain where that the misunderstanding came from although… on reviewing the video it’s a badly worded answer.”

The inquiry then saw that Mr Jenkins had emailed Mr Evans after the conference to continue to raise the point and made an invitation to produce an industry guidance note to clear up any confusion about ACM.

Further emails showed Mr Jenkins taking the concerns to Brian Martin, a senior civil servant then responsible for the Approved Document B guidance, in February 2016.

Mr Jenkins warned that “there is much confusion and misunderstanding” in the industry. “I do think the current situation is of grave concern,” he wrote. “Surely this justifies the requirement for a less ambiguous statement of the rules?”

But Mr Martin responded saying that he was “not sure the text [of Approved Document B] is really that ambiguous” and said “people often argue that it isn’t clear when they are trying to justify doing something that is clearly wrong”.

He added that: “It’s for the designer and building control body to consider if [the regulation] has been met.”

He claimed that the word “filler” had been added “deliberately… to address things that form part of the cladding system”.

However, this was the part of the guidance believed to be ambiguous, as it was contained in a section covering ‘insulation’ and was therefore not widely understood to refer to external cladding panels which have no insulating function.

This has been a topic of major debate since the Grenfell Tower fire, with the government writing to industry just days after the blaze to clarify that “for the avoidance of doubt” the word “filler” referred to the internal core of an ACM panel.

Industry figures have previously accused them of attempting to use this argument to avoid liability for the widespread use of ACM, and today’s evidence marks another clear moment when the department and Mr Martin were clearly warned of the ambiguity surrounding this guidance.

Mr Evans was then grilled about NHBC’s decision to publish guidance in July 2016 which expressly permitted the use of ACM and combustible insulation in cladding systems.

Two years earlier, the NHBC had helped draft guidance which said cladding systems could be signed off as compliant by fire engineers even if they were not tested through a ‘desktop study’ assessment of tests on similar systems.

Mr Evans explained that the July 2016 guidance was based on systems which were frequently approved through these desktop studies.

“How was that possibly consistent with Approved Document B?” asked Mr Millett.

“We had seen at this point [desktop] assessments which when assessed were deemed to satisfy [the regulations] via their desk desktop assessment route,” Mr Evans said. “We then put a specification in place which we felt from that evidence we would be willing to accept as demonstrating compliance with [the regulations].”

“Was this a desperate attempt by the NHBC to give some validity retrospectively to the commonly used wall build ups which NHBC had been approving?” asked Mr Millett.

“No,” replied Mr Evans.

“You see, by this time the use of combustible materials had been referred to variously as a ‘ticking time bomb’… ‘an accident waiting to happen’… and of grave concern. Why was NHBC, who was well aware of those potential problems, now easing the passage of compliance for combustible materials rather than making things tighter?” asked Mr Millett.

“I wouldn't consider it at that point that we'd eased the passage. We had carried out a great deal of work in satisfying ourselves and gaining information from experts in this area that we could justify issuing that note and accepting those constructions,” said Mr Evans.

Mr Evans was then shown post-Grenfell spreadsheets covering dozens of buildings with combustible ACM which the NHBC had signed off. These included New Capital Quay in south London, which is believed to be one of the largest affected blocks in Europe.

“Are you able to explain how it was that NHBC, with the high standards that you told us about… managed to sign off a number of very large projects made up of 1000s of people's homes when they didn't comply with the building regulations?” asked Mr Millett.

“NHBC don't build buildings. We were on site for a limited amount of time. It's the builders responsibility to build in accordance with the building regulations,” replied Mr Evans.

The inquiry has previously heard how NHBC challenged insulation manufacturer Kingspan over the combustibility of its product, but continued to sign off its use despite the lack of further test evidence.

Asked at the end of his evidence what he would have done differently, Mr Evans said he would have “been more assertive” with the manufacturer.

“Evidence for the inquiry has revealed that they weren't just delaying things, they were, in some cases, lying,” he said.

The inquiry will now break for Christmas and oral evidence will resume on 24 January.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters