You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Councils and prisons sending homeless people to Birmingham due to abundance of exempt accommodation

People from across the country who are experiencing homelessness or leaving prison are being sent to Birmingham by councils and probation services because of the high number of exempt accommodation properties in the city, it has emerged.

Inside Housing has spoken to a number of sector figures and seen evidence from providers which have confirmed that a large percentage of individuals living in exempt properties have been sent from different parts of the country, often referred by councils.

This is backed up by research from Birmingham City Council, which estimates that only 42% of the people currently living in exempt accommodation in Birmingham are from within the city’s boundaries and require support.

Exempt accommodation is often used as a means of housing those with very few other options, such as prison leavers, rough sleepers, refugees and migrants, and those experiencing substance misuse issues.

Read our full investigation into Birmingham’s growing exempt accommodation problem here

Because such landlords provide loosely defined care and support services, their tenants can be exempt from housing benefit caps and associations can charge much higher rents than regular landlords.

In many cases, exempt accommodation offers housing and support for those most in need, but there have been widespread issues with some providers, which are using the system to secure profits without supporting tenants.

In the past eight years there has been a boom in exempt properties. Birmingham has seen a uniquely large rise in the number of such properties, with other major cities seeing nowhere near the level of growth in the UK’s second-biggest city.

And it now appears that much of this is driven by councils dealing with their homelessness problems by sending those presenting as homeless to Birmingham, with the knowledge that they could be housed in exempt accommodation.

Dominic Bradley, chief executive of housing provider Spring Housing, explains: “At an operational level, we know that people presenting to other councils are, overtly sometimes, but also less explicitly, being directed to providers in Birmingham.”

Other figures working in housing in Birmingham have told Inside Housing that in some cases providers have close relationships with authorities outside of Birmingham and automatically refer people to certain providers.

This is backed up by evidence from Prospect Housing – a provider that pulled out of the market last year after raising concerns about the model – which said that many of its residents came from outside of Birmingham and that their local authorities had “provided them with a train ticket and a sandwich and directed them to the city”.

There are also an increasing number of prison leavers from across the country being sent to Birmingham on their release.

Thea Raisbeck, a researcher at the University of Birmingham and author of Exempt from Responsibility?, a report on Birmingham’s exempt accommodation, said: “I identified in 2018 that probation officers and prisons from around the country have seen Birmingham as the easy way to get difficult cases housed, often seemingly bypassing West Midlands probation. That was in 2018, and it is still happening now.”

Mr Bradley has also seen this trend. He said: “What is the hardest thing for prison resettlement teams? It’s housing. If you have got providers saying we will take whoever you have, they jump at that.”

Inside Housing has heard that some providers have direct links to councils and prisons, and that they even hire drivers to collect those being sent to Birmingham from the train station.

This is backed up by work carried out by Birmingham City Council, which has found a mismatch between locally needed provision and the number of exempt properties in the city.

According to its research submitted to the select committee looking into exempt accommodation, of the 21,000 exempt bedspaces in the city, only 9,000 were needed to meet local need. This meant the remaining 12,000 bedspaces were occupied by people from outside of Birmingham, as well as filling some affordable housing gaps.

When Inside Housing went to Birmingham to investigate exempt accommodation, we spoke to exempt accommodation residents from Hereford, Cheshire and London, who had been sent to Birmingham because of the abundance of such housing.

To try to stem the flow, Birmingham City Council has been in discussions with providers about the issue, as well as making agreements with partner organisations – including the prison and probation services – that they will not send anyone a provider that is not signed up to its city-wide exempt quality standards and charter of rights.

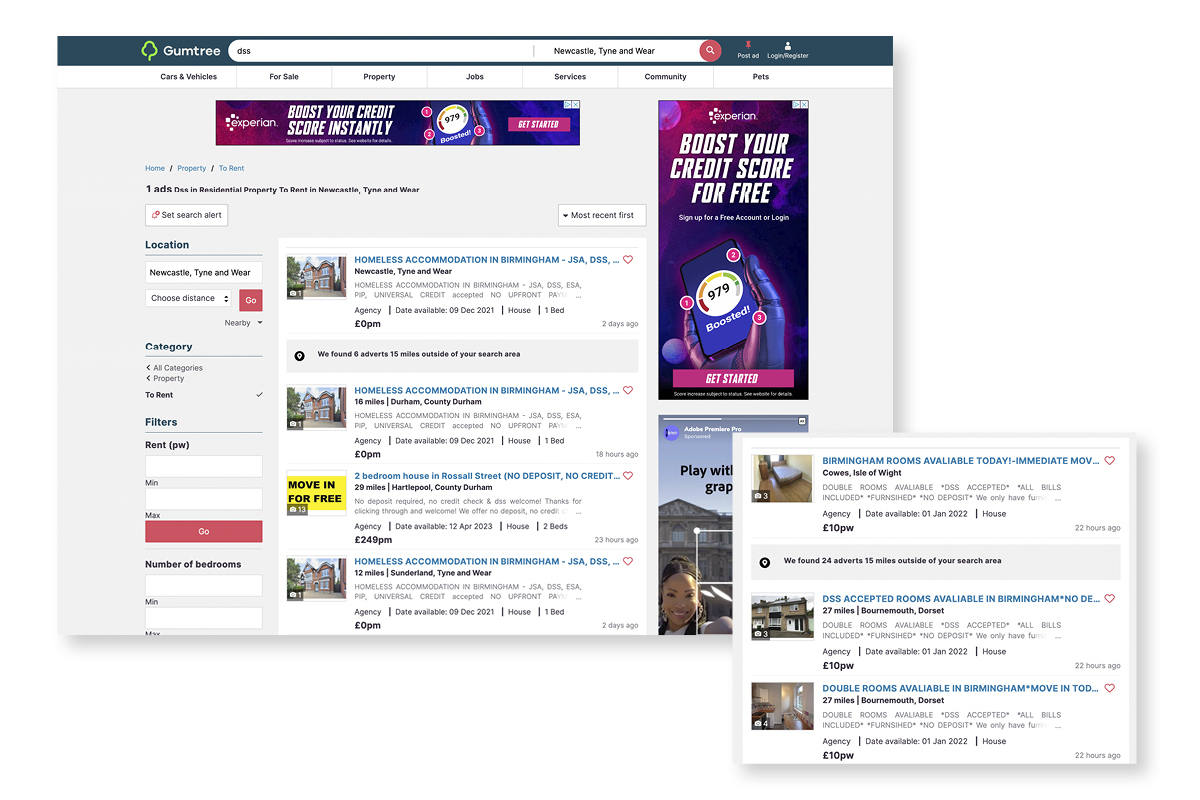

However, it has emerged that a number of people in search of housing from other areas in the UK are also coming to Birmingham, lured by adverts posted by providers on Facebook and Gumtree offering housing for cheap rent to those on benefits.

Gumtree is a particular hotspot for these type of adverts, with landlords taking over local housing pages for various area across the country and promoting cheap accommodation in Birmingham.

In most of these adverts, they offer housing exclusively for people on benefits, with no upfront payment and rents of around £40 a week or lower.

Inside Housing spoke to a whole household of people living in exempt accommodation. They had moved up to Birmingham from areas as far away as the Isle of Wight after seeing these adverts.

A spokesperson for Birmingham City Council said: “BCC has long recognised that many people in exempt supported housing in Birmingham originate from outside the city.

“As a result we have been in discussion with registered providers and partner organisations about this and in response drew up the quality standards for landlords and the charter of rights for tenants.

“We have also been aware that advertising websites like Gumtree are being used by providers to send vulnerable people from long distances to the city and have made representation to the government that greater controls are needed so vulnerable people are not taken advantage of.

“The extension of our pilot project to 2025 with the funding from DLUHC will enable us to continue to monitor and regulate the sector, including encouraging more landlords to sign up to our quality standards and charter of rights.

“However, the government now needs to act as a matter of urgency to reform the sector, including giving local authorities the powers to limit the growth in the number of units, and more importantly drive out those poor providers who are failing to offer adequate or appropriate support, or where there is clear evidence of criminal activity.”

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters