You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

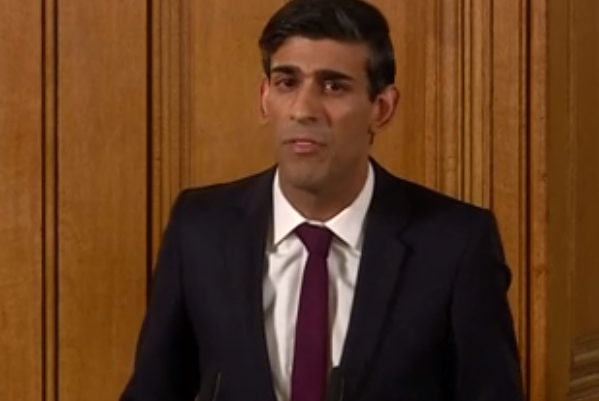

What can we expect from prime minister Rishi Sunak on housing?

Rishi Sunak has become Britain’s third prime minister in two months. From the green belt to making renters “capitalists”, Ella Jessel runs through what we know about the prime minister’s housing priorities

Britain has another new prime minister. Liz Truss has exited after a calamitous 44 days in office, and Mr Sunak, the former chancellor of the exchequer, has stepped up to the plate.

In a month replete with policy rethinks, this was the Conservatives’ most dizzying U-turn yet. Seven weeks ago, Mr Sunak had just been roundly beaten by Ms Truss in a leadership race; yesterday, he stood outside Number 10, pledging to fix her “mistakes”.

The Southampton-born former hedge fund manager’s position on the economy is well known, but what are his views on housing, and what can we expect from him on policy?

Building and planning

Housing was far from a central plank of Mr Sunak’s recent leadership campaign, but he did give a brief outline of his priorities during an online hustings with ConservativeHome.

In this debate, the MP for Richmond in Yorkshire said he wanted to increase housebuilding by densifying inner-city areas, stopping developers “hogging” land, helping smaller builders and delivering more homes through modular construction.

But there are question marks over whether a Sunak government will really go for broke on housebuilding, not least because he has said he no longer intends to meet the Tory manifesto commitment to build 300,000 homes a year in England.

In an appeal to the Tory faithful, Mr Sunak also pledged to block housebuilding on the green belt, and said he would stop councils appealing to the Planning Inspectorate to declassify areas of green-belt land by updating their local plans.

This stance was criticised by Robert Colvile, director of the Centre for Policy Studies, the think-tank, who accused him (and Ms Truss) of “pandering to Tory nimbys” and “peddling the fantasy” that homes could be built where “no one will notice”.

This campaign pledge is also a sign that Mr Sunak might take a more socially conservative approach to planning than Boris Johnson. Mr Johnson’s radical reforms, driven by Robert Jenrick, the housing secretary at the time, generated a huge backlash from voters in the Tory heartlands and were blamed for the party’s by-election losses in 2021.

Many of these were unpicked by Michael Gove when he replaced Mr Jenrick. He issued his own bill, which did not include many of Mr Jenrick’s plans. With the new PM putting Mr Gove back in the hot seat at the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, we can expect the proposals in this bill pushed forward.

Social housing

In his role as chancellor, Mr Sunak announced housebuilding schemes including a £12bn Affordable Homes Programme, welcomed by the sector as one of the largest settlements in years. The last Autumn Budget also included a £1.8bn brownfield development fund.

However, if his previous comments are anything to go by, the new prime minister seems unlikely to champion social housing. In the ConservativeHome hustings, he praised Mr Jenrick for “shifting” the affordable housing budget away from rental properties and making private sale homes – such as shared ownership units – count towards affordable housing contributions.

Expanding on this in an interview with Sky News, Mr Sunak said he wanted young renters living at home with their parents to be “capitalists” through homeownership.

“We can’t expect future generations to share our belief in capitalism if they can’t get their hands on capital,” he said.

Building safety crisis

As chancellor, Mr Sunak announced a £1bn Building Safety Fund in 2020 to remove dangerous cladding of all types from high-rise buildings. This followed months of campaigning for a building safety fund not limited to aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding.

This fund was later increased to £5bn, but still was not deemed to be enough to deal with the costs of other fire safety defects such as timber balconies, or missing fire breaks and cavities. Yet it seemed this was Mr Sunak’s red line. Under his watch, the Treasury turned down requests from two housing secretaries for more money.

Talking about his attempts to secure more cash from Mr Sunak, Mr Jenrick said: “I have fought this battle for a number of years. The Treasury and the government aren’t willing to do that.”

Later, once Mr Gove had replaced Mr Jenrick, he was given permission by Simon Clarke, the Treasury’s chief secretary at the time, to use a “high-level threat” of tax or legal solutions to get money from developers. This agreed package for medium-rise buildings was, however, “conditional on no further exchequer funding”.

Following yesterday’s cabinet reshuffle, Mr Sunak has now reinstated Mr Gove as housing secretary, three months after he was sacked by Mr Johnson. Many leaseholders hope Mr Gove can pick up where he left off and push forward the changes he launched to fix the building safety crisis.

Levelling up and welfare

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Mr Sunak was known for his big public-spending schemes as chancellor. He opened an unlimited fund to guarantee 80% of wages for “furloughed” workers, and announced an unprecedented expansion of the welfare system.

It included a £20-per-week boost to Universal Credit and a realignment of Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates to cover the cheapest third of rents. However, these policies were short-lived. The £20 uplift was later removed and LHA rates have been refrozen since 2020.

As for the levelling-up agenda, in his first speech as PM, Mr Sunak briefly recommitted to the government’s 2019 promise to redistribute wealth across the UK. But with talk of “difficult decisions”, it’s unclear how the flagship policy will play out.

Mr Sunak’s critics have questioned whether the ex-banker’s wealth – he and his wife have a personal fortune of about £730m – means he will struggle to relate to the day-to-day struggles of voters. A video of him speaking to Tory party members in Tunbridge Wells did nothing to dispel this impression, when he stated he reversed Labour policies which “shoved all funding into deprived urban areas”.

When challenged by ITV journalist Daniel Hewitt, Mr Sunak doubled down on the remarks, arguing there were pockets of poverty that “exist everywhere, they are not just in big urban cities”.

Freeports

One of the policies introduced during Ms Truss’s brief time as prime minister was the Investment Zone initiative, which encourages councils to “go for growth”, with “streamlined” planning processes and low taxes.

Applications have already opened, with the West Midlands Combined Authority submitting plans to build up to 18,000 homes as part of the scheme. But whether it will survive under a new government is in doubt.

The more fiscally conservative Mr Sunak seems unlikely to keep a policy that was criticised for handing out unlimited tax breaks. Ms Truss’s iteration of Investment Zones also involved loosening planning restrictions that could come into conflict with Mr Sunak’s pledge to protect the green belt.

However, as chancellor, Mr Sunak introduced the very similar Freeport initiative, which has now been rolled out across eight areas in the UK. He could just rebrand it.

The energy crisis and decarbonisation

One of the biggest challenges facing Mr Sunak is the energy crisis, with household bills tipped to soar to about £3,200 in October.

In light of the situation, Mr Sunak told The Times during his campaign to become leader of the Tory party that he would consider “refocusing” attention on a nationwide insulation programme for low-income households.

Before his departure, Mr Johnson was trying to find £1bn for the insulation scheme. Many suggested it could come from the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme, which aims to improve energy efficiency in schools, hospitals and other public buildings.

It was thought it was too late to divert funds from the £450m Boiler Upgrade Scheme, which offers households up to £5,000 in subsidies to replace their ageing gas boiler with an energy-efficient heat pump.

Mr Sunak’s record on climate change is not strong. He has consistently voted against policies to tackle the global crisis. In 2016, he voted against lowering the maximum rate of carbon dioxide emissions in new homes, and against establishing a decarbonisation target in Britain.

However, as chancellor he did introduce some measures to mitigate climate change, such as the heat-pump scheme and the removal of VAT on green technology such as solar panels.

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters