You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The Homeless Period

For homeless women, accessing tampons and sanitary pads can be difficult - even in shelters and hostels. But a petition to change that has gained almost 100,000 signatories. Dawn Foster reports

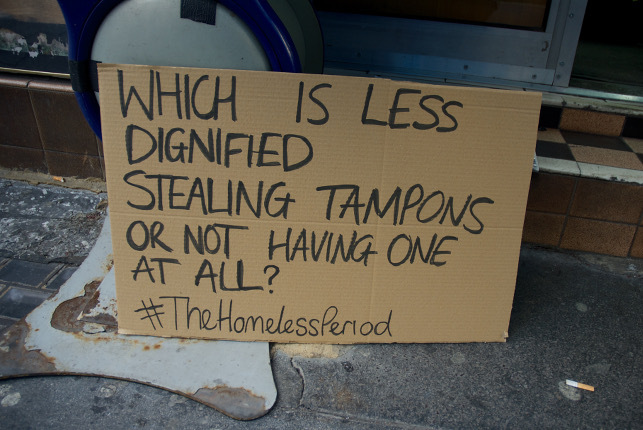

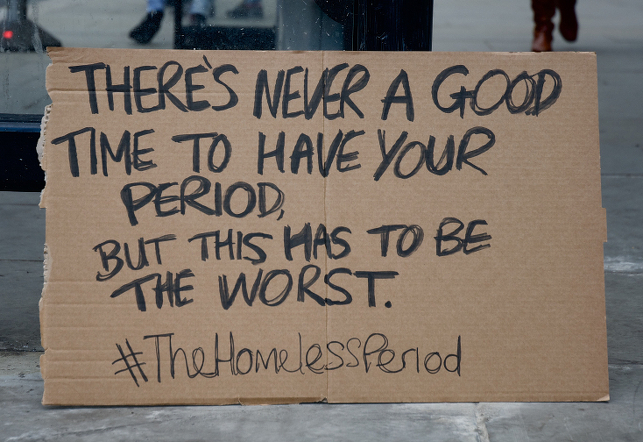

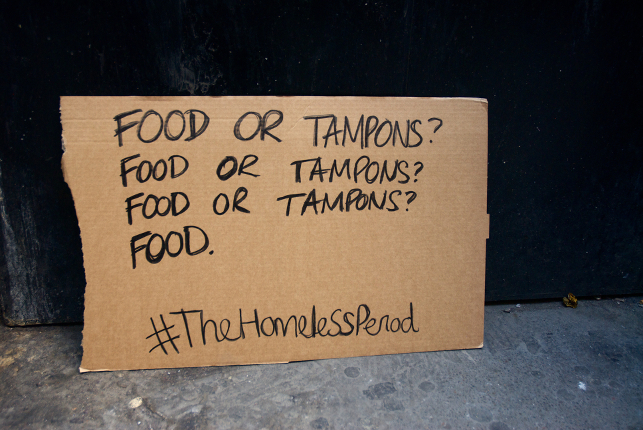

An image created by The Homeless Period campaign to highlight the lack of funding for tampons and pads for homeless women

Much of the discomfort of street homelessness is easy to imagine - the biting cold, fear, broken sleep, and psychological toll of trying to survive without money and shelter. Reporting crime becomes difficult when there is no fixed address for police to visit and take a statement.

Other more everyday aspects of life we take for granted often get forgotten, however. But for many homeless women, the discomfort of menstruation is intensified by their situation.

“I used to just get loads of tissues from public loos, instead of pads, but it’s a mess.”

Jill, a homeless woman

A campaign started by a group of friends interning in advertising agencies aims to change this, however. Called The Homeless Period, the campaign includes a petition which quickly attracted almost 100,000 signatures. If it reaches this threshold, MPs must consider debating the issue in parliament.

The campaign calls on the government to fund sanitary protection for women in shelters in the same way it currently funds condoms and sexual health products – through local clinical commissioning budgets. The campaign’s site also encourages people to find their local homeless shelter, and donate tampons and pads.

So why was the campaign launched? How serious is this issue for homeless women? And are homelessness services doing enough to meet the needs of their menstruating service users?

Shelters rely on donations to cover the cost of tampons

Overlooked need

In a McDonald’s off Trafalgar Square, Jill, a homeless woman in her late 20s, explains over a cup of coffee how embarrassing she found dealing with menstruation when she first became homeless. ‘I used to just get loads of tissues from public loos, instead of pads, but it’s a mess. And you’ve got no clean underwear,’ she says. ‘You feel dirty anyway, don’t you. But you just feel disgusting and there’s nothing you can do.’

Jill has slept rough on and off for six years with her boyfriend, and looks far older than her age as a result, with weathered skin and hollow cheeks. Sometimes, she says, she asked women queueing for public toilets if they had any spare tampons or pads, but says women either recoiled, or cut her off before she even spoke, assuming she was begging for change.

“Once they are settling into the accommodation, they might have the first period they’ve had in a long time.”

Esther Sample, women’s strategy manager, St Mungo’s Broadway

Day to day, this isn’t the biggest problem facing women who are street homeless, but it makes a grim experience harder and more demeaning for many vulnerable people.

Esther Sample, women’s strategy manager at homelessness charity St Mungo’s Broadway, says: ‘Our female clients have told us that managing your period on top of many other issues can be an extra problem. For women who are rough sleeping, or in more hidden homelessness situations, this can be even harder.’

Oli Frost, Josie Shedden and Sara Bakhaty set up the campaign, which hopes to ensure that homeless women are not left in this situation. ‘We read an article about the issue which we found very moving. It was something we’d never thought of before. We talked about it with a lot of other people and they all told us the same. So we thought it would be good to make a campaign that changed that,’they tell me via email. Indeed, they have struck a chord for many who’d never considered the issue and received an outpouring of support.

The level of support and action the campaign has received has surprised the group: ‘For most people it’s sharing and signing the petition. We have 91,000 signatures now. But others have gone further and donated or set up their own crowdfunds,’ they explain in an email. ‘It’s now getting hard to keep track of all the smaller local movements that have been set up. So we don’t know exactly how much has been donated as a result. Certainly a few thousand pounds now.’

The stress of sleeping rough can cause some to have irregular periods

Not a priority

St Mungo’s Broadway has a small client welfare budget it uses for toiletries and sanitary products, but also relies on donations to provide sanitary products for women in their services.

Nationwide, around one in 10 people on the streets are female, but St Mungo’s Broadway says around a quarter of people in its services are women. Contraception is provided from local health budgets free of charge, but extra funding for women’s sanitary projects would be welcome. Ms Sample says: ‘Quite often we do rely on donations. I think if we were able to get that from health providers, that might be useful.’

It meets the demand through the donations and other parts of the budget, but is clear that funding would free up much-needed cash that could be use to ensure clients are given a better chance at breaking the cycle of homelessness.

Attempts to quantify the scale of the problem highlight the issue: most services predominantly serve men, and despite repeated attempts to contact similar homelessness services, including Thames Reach and Homeless Link, no responses were forthcoming. Senior figures in housing mentioned off the record they worried that with deep cuts both underway and projected in the sector, services weren’t keen to ask for more when they were aggressively told to expect far less.

However, this is a serious issue for their clients. The stress and tumult of sleeping rough, as well as malnutrition and substance abuse for some women, can also cause monthly cycles to become irregular, or cease altogether.

Jill says her periods resume if she’s in a hostel for a while, but is struggling with substance abuse at the moment so hasn’t had a period for a few months – a common occurrence according to homelessness workers.

‘That might mean that when they’re coming into our services, once they are settling into the accommodation, they might have the first period they’ve had in a long time,’ Ms Sample says. ‘That can be quite upsetting, because they’re not ready for that. So it’s good to have resources to support women in that circumstance.’

Few people responding to the campaign had considered that menstruation might be an issue. Homeless women’s issues are often overlooked because most street homeless people are men.

With the vast majority of service users being of one gender, it’s commonplace for overarching policies to consider the non-gendered experiences of homelessness.

New awareness

For women like Jill, it’s not a life or death problem, but having services able to provide sanitary protection free of charge would make her feel ‘a little more human, and looked after.’

And with council budgets slashed, and homelessness services often bearing the brunt, spending on anything outside of core services and bed provision looks set to be in jeopardy.

A commitment in the health budget for women in shelters would ease the pressure on hostels and shelters, and allow them to shore up homeless women’s dignity.

Oli, Josie and Sara are keen to press on with the campaign and are buoyed by the support. They say: ‘With 100,000 signatures, parliament has to consider debating the issue. So that’s what we’ll do next.’

Women and homelessness

- Women made up 26% of people who accessed homelessness services in 2013

- 50% of St Mungo’s female clients have experienced domestic abuse

- 786 women were recorded sleeping rough in London last year

- 20% of women accessing homelessness services became homeless to escape violence from someone they knew, with 70% of these fleeing violence from a partner

- 60% of homeless women have slept rough, but only 12% have engaged with street outreach teams

Sources: Crisis and St Mungo’s Broadway