The finance frontier

On 28 March local authorities will boldly go where they have never been before as a new era of self-financing dawns. Keith Cooper finds out if they are ready for their journey into the unknown.

Stardate: 28 March 2012. As the sun rises council housing bosses in England will find themselves looking over a brave new world. The 171 authorities which still own homes will find themselves floating free of the much-hated housing revenue account: the centralised regime which allowed Whitehall, rather than town halls, to decide how their tenants’ rents should be spent.

Around a quarter of stock-owning authorities - 33 - will be better off as the government clears £5.3 billion of their housing debt. The majority of authorities, however - 136 - will embark on their self-financing voyage carrying more of a financial burden. As part of the deal, the government has split the £13.4 billion of historic housing debt held by councils, between them.

The offloading of this princely sum onto cash-strapped councils’ backs will place local authorities under varying degrees of strain. They’ve been given the freedom to explore new frontiers, but some will be so severely weighed down by debt, they will be unable to journey far. Others, however, will be able to boldly go and build new homes and spruce up their properties to a standard well beyond the ‘decent’ one set by the last government. So what will set councils apart from each other in this new era?

Councils’ ability to launch themselves into ambitious schemes is not simply determined by whether their debt goes up or down. For example, Southwark Council will have £200 million wiped off its debt, yet it will initially be in a worse state than before it became self-financing. Housing policy advisors and consultants point to three critical factors which influence local authorities’ capacity to make the most of their new-found independence.

The first and second of these are the two types of ‘headrooms’ in the 30-year business plans which authorities have drawn up for their futures under self-financing. The third factor is something best described as ‘gumption’ or ‘guts’: their willingness to prudently manage higher levels of debt rather than clearing it as quickly as possible out of fear of the minus sign.

The pay-off

‘My sense is that there are a number of authorities that don’t like debt full-stop,’ says Steve Partridge, managing director of Chartered Institute of Housing Consultancy, which has helped many councils with their business plans. ‘They will do whatever they can to pay it off as quickly as possible. But that isn’t the majority.’

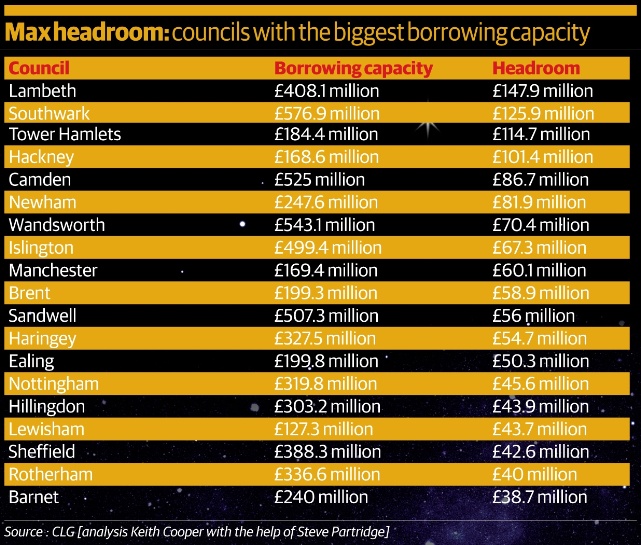

The headroom in authorities’ business plans are for ‘borrowing’ and ‘revenue’. The former is determined by a borrowing cap which the government has set for each authority. This places a ceiling on the amount of debt they can rack up. The borrowing headroom is the space between their starting level of debt and the cap. Most local authorities will, of course, see this starting debt soar into the stratosphere as they help pay off the historic £13.4 billion they collectively owe the government.

Lambeth Council’s £408 million cap creates the largest borrowing headroom of £148 million. Southwark comes in a close second with a borrowing headroom of £126 million thanks to a £577 million cap.

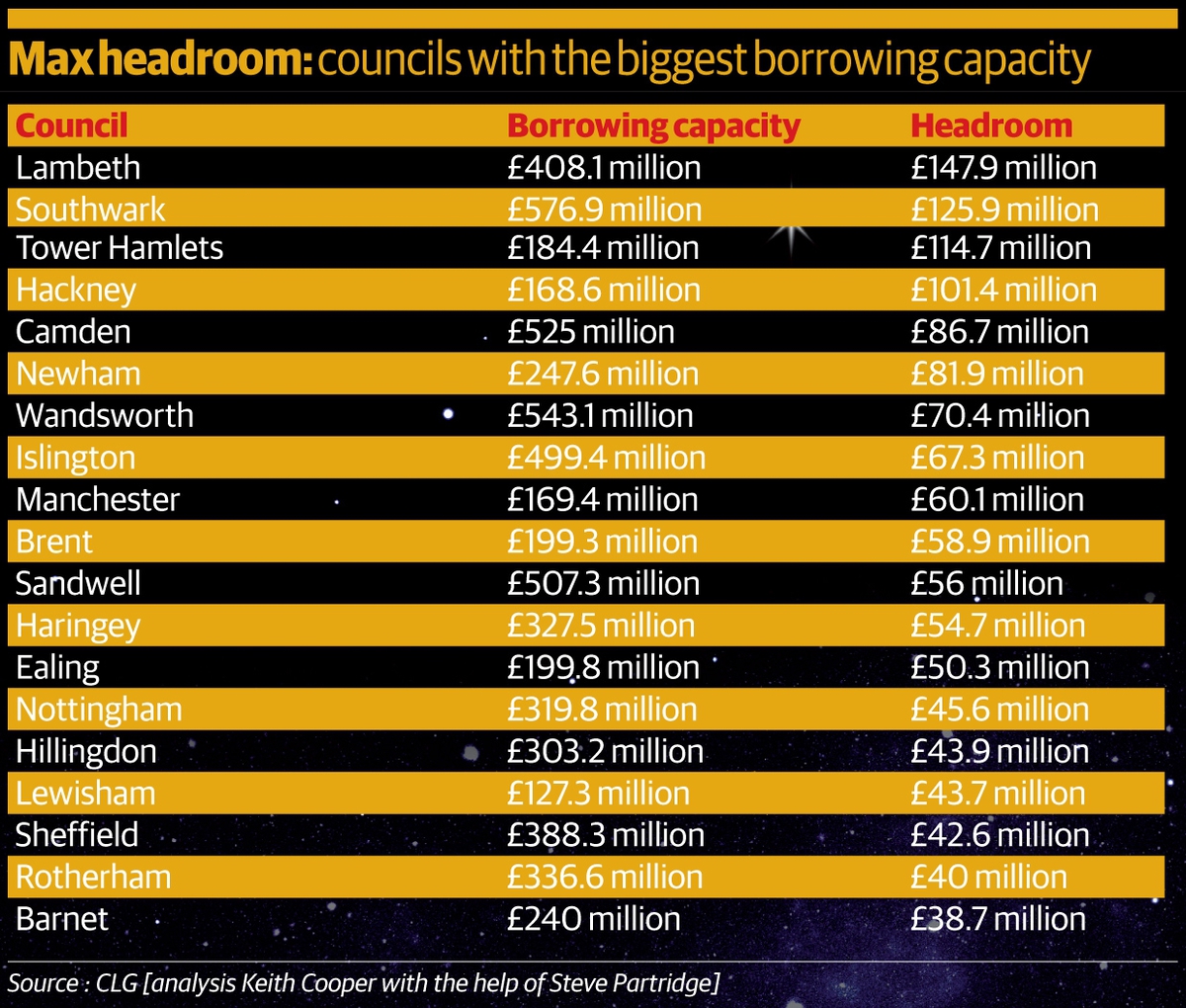

In total, the government had given the nod to an extra £2.9 billion of local authority borrowing. Our analysis shows that just four councils have a borrowing headroom exceeding £100 million. Three-quarters have the capacity to boost their loan portfolios by between £1 million and £50 million.

Not all councils will - or can - rush to the City with their borrowing requests, however. Southwark, for example, has no plans to make use of its £148 million headroom during the next five years. The reasons for this seeming reticence are twofold: it is still saddled with high-interest payments from its house building sprees in the 1960s and 1970s and it lacks the necessary ‘revenue headroom’ to service any new loans.

Spending spree

Revenue headroom is essentially the surplus that authorities make on rental income after paying their bills. Waverley Council, which campaigned vigorously for the self-financing regime, has immediate plans to spend its £4 million revenue surplus on house building and refurbishment programmes - something it was unable to do under the HRA.

Not all local authorities will be so quick off the mark, according to Matthew Warburton, policy advisor for the Association of Retained Council Housing, which represents around half the self-financing authorities. ‘There is a certain amount of caution,’ he says. ‘They don’t want to take risks until they are used to working with these arrangements.’

He predicts that most authorities will focus on refurbishment programmes before embarking on ambitious building programmes. ‘I think first of all, most councils will take the opportunity to catch up on repairs to existing stock which they couldn’t do previously.’

Proceeding with caution

John Whitehouse, associate director at consultancy Sector, agrees that some councils are taking a careful approach. Some tenants may have to wait some time before feeling the benefits of the new self-financing regime, he adds.

‘They [councils] are prepared for the self-financing regime but I am not convinced they are geared up to spend any additional resources. In the immediate future we will see little change.’

While all local authorities must have their business plans agreed before 28 March, many are yet to work out the finer details, such as where surplus revenue or new loans will be spent. Lincoln Council, for example, will first quiz its tenants about what they want before setting its plan in stone.

A rise in building

The CIH’s Mr Partridge thinks local politicians’ enthusiasm for new homes could, however, prompt a quick-sharp rise in the number embarking on building programmes. The 22 local authorities which have already begun house building programmes will shoot up to 122 within the next three to five years, he predicts.

‘A very great number of authorities could be building [new homes] within the next few years,’ he says. ‘I think the appetite is there, even in the smallest districts.’

Regeneration and development is likely to be the most popular of the four main areas into which councils channel their resources, believes

Mr Partridge: ‘It is the one that lights up members’ eyes’. Surplus cash could also be used to introduce new services, make existing homes more eco-friendly or pay off debt, he adds.

One authority which has already put a number on the new homes it will build is Cambridge. The city hopes to build 250 properties over the first five years of its business plan. This will be funded in part by its £16 million borrowing headroom.

Julia Hovells, finance and business manager at the city authority describes the self-financing regime as a new territory. ‘The big difference for local authorities is the move from annual settlements from the government in the national HRA financing system to an environment where you know what your debt is from day one so you are able to plan more effectively to meet local needs.’

Waverley Council is also planning to make the most of its new found freedom - it’s venturing into previously unexplored worlds.

‘We were so used to having no money to spend. Now we have the opportunity to invest in our stock and increase it,’ sums up Angela Smithers, head of housing at Waverley. ‘We will be a bit busy.’

Southwark: weighed down by the past

Number of homes: Just under 38,800

Debt paid by the government: £200 million

Headroom: £126 million

The capital’s largest local authority landlord appears to be one of the biggest winners from the self-financing regime - on paper at least. Official calculations assume Southwark Council has the capacity to borrow up to £126 million to fund new homes and refurbishment schemes.

There are two factors undermining this superficial assumption. First, the authority is still lumbered with relatively expensive repayments on loans taken out for its house building spree in the 1960s and 1970s. ‘We are paying a higher interest rate than anyone else because of the time that we got the money [due to high interest rates fuelled by oil prices and government spending],’ explains Ian Wingfield, cabinet member for housing management at Southwark. ‘And now is probably not the best time to refinance’.

The London borough is also hampered by historically low rents. It will be some time before its rental income makes increased borrowing a possibility.

‘Our baseline is unable to support the cost of any additional borrowing for the next five years at least,’ Mr Wingfield says. ‘We are not opposed to the system but we are one of the few authorities where it is going to be pernicious in the short term.’

Waverley: in excess

Number of homes: 4,884

Debt payment to government: £188.8 million

Headroom: negligible

This Surrey authority was at the vanguard of efforts to dump the former housing revenue account regime. A look at its business plan reveals how its campaign has paid off. Under the HRA subsidy system, Waverley returned more than half its rental income, around £12.5 million, to the Treasury. Loan repayments on its £188.8 million debt will cost around £8 million, leaving it with a £4 million surplus. This makes Waverley a good example of an authority for which the new system delivers ‘revenue’ headroom but no borrowing headroom.

The council has split its 30-year business plan into three main parts, explains Angela Smithers, its head of housing. During years one to five, half its surplus will pay for new affordable homes; the other half for a much-needed refurbishment programme. ‘We have been quite starved of cash,’ Ms Smithers says. ‘We didn’t meet the decent homes standard, but now we’re geared up for it. We are using the investment to meet the standard by 2015.’

Waverley will make interest-only payments on its loan during this first period to ensure tenants see early benefits. Capital loan payments will begin in years six to 10, taking up one-third of its surplus; its new homes and refurbishment programmes will each get one third. The final two decades of the council’s 30-year plan sees half its surplus go toward loan repayments, while new build and refurbishment schemes get a quarter each.

Cambridge Council: use your headroom

Number of homes: 7,360

Debt payment to government: £214 million

Headroom: £16 million

The self-financing regime will end Cambridge Council’s status as a debt-free authority. On March 28 it will have to transfer a cool £214 million to the government in exchange for the right to control its own finances. Julia Hovells, finance and business manager at the city authority, says the payment will shift it to a position of significant debt.

‘This is a new area for many local authorities,’ she says. The council has come up with a ‘prudent’ business and asset management plan which will allow it to build more than 250 homes in the first five years. It also allows for a further 400 homes to be funded in years six to 15 of the plan, should council members so wish.

‘Cambridge has some headroom in the business plan, which not all local authorities have,’ explains Ms Hovells. ‘We have £16 million of headroom which allows us to borrow against that additional headroom.’

The self-financing regime will make it easier for Cambridge to make plans to meet housing needs, she adds.

Lincoln Council: the tenants’ choice

Number of homes: Just under 8,000

Debt payment to government: £25 million

Headroom: £7 million

Lincoln Council will refine its business plan over the next year after canvassing the views of its tenants. The consultation will first ask where the local authority should spend the £7 million of extra borrowing power its self-financing settlement allows. Potentially on offer are new homes, beefed-up security, and other improvements like new fencing and door entry systems, which the financial burden of hitting its decent homes target previously pushed out of reach. Its tenants could also opt to restore day-to-day services which suffered cutbacks in order to free up decent homes funding.

‘We had to make significant cuts in the revenue budget to make the necessary contributions to our capital programme,’ says John Bibby, director of housing and community services at the local authority. Although it met the decency target, it expects to spend £60 million over the next five years to maintain the standard and deal with health and safety issues, such as asbestos removal.

Council members and tenants will also help decide how much of the rental income should be channelled into debt repayments and how much reinvested in new homes and improved services.

‘We could go completely debt-free in 24 years,’ Mr Bibby adds. ‘There are some strategic decisions we need to work through with tenants and [council] members: whether we go debt-free or whether we maintain a level of debt which can be topped up and serviced from income.’