Sent away: the social rent shortage is driving London councils to move more homeless people out of the city

As Inside Housing launches its Build Social campaign, Grainne Cuffe reveals how a shortage of affordable housing is leading London councils to ship more homeless people outside the capital – and where they are being sent

“If there isn’t some intervention soon, the homelessness sector is looking on the brink of collapse.” That was the assessment of Candida Thompson when she spoke to the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for London last month. Ms Thompson, assistant director of housing needs at Newham Council, said that the homelessness and temporary accommodation situation is the “worst” she has “ever experienced”.

And the raw numbers suggest that she is not wrong. In July, government statistics showed that the number of households in temporary accommodation in England had hit a 25-year high: nearly 105,000 households, including more than 131,000 children.

The situation is particularly acute in London. On 31 March 2023, 16.5 out of every 1,000 households in London were living in temporary accommodation, compared with 2.2 per 1,000 in the rest of England. A chronic housing shortage, soaring rents and the ongoing freeze on Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates are all contributing to the crisis.

Between them, London councils are collectively spending £52m every month on temporary accommodation.

One worrying effect of this crisis is that these councils are housing growing numbers of their most vulnerable residents outside the capital, away from vital services and support networks. In 2021, an analysis by Inside Housing revealed that councils across England had placed more than one in four homeless households in temporary accommodation outside of their own borough boundaries due to a lack of suitable local accommodation.

Inside Housing decided to investigate further after we heard from homelessness sector sources that local authorities outside London were struggling to house their own homeless people because they are increasingly having to take on temporary accommodation placements from London boroughs.

Problems for councils

We sent Freedom of Information requests to London councils, to try to find out the scale of the issue. A total of 29 London councils told us they sent 1,693 homeless households to accommodation outside the capital between March 2022 and February 2023, in one instance more than 200 miles away in Liverpool. That equates to 7.8% of all temporary accommodation placements.

Darren Rodwell, executive member for regeneration, housing and planning at London Councils, says that “boroughs have generally been able to keep the proportion of out-of-London placements below 5% or 6% for the past few years”, but he accepts that “we have started to see an increase now”.

The figures obtained by Inside Housing echo data provided by London Councils which show that the total number of out-of-London placements has risen over recent years, from 2,122 in 2015-16 to 2,580 in 2022-23. London Councils’ data includes the out-of-London data for all boroughs for each financial year from 2015-16, except for Bexley from 2021-22 onwards. It does not include the overall number of temporary accommodation placements, so cannot provide a percentage.

Inside Housing’s FOI request also asked where London households were being sent. The areas receiving the most households were Medway (185), High Wycombe (155), Thurrock (152), Dartford (130) and Harlow (97). London boroughs sending the most households outside their local area were Redbridge* (291), Brent (180), Greenwich (170), Bromley (149) and Hillingdon (111).

Notes: 1. Camden did not supply enough data; 2. Hackney did not respond to Inside Housing’s FOI request; 3. Harrow did not receive an FOI request; 4. Hounslow has not been recording temporary accommodation data because of IT system problems

The trend is causing significant problems for the councils in the places people are being sent. Bearing out the tip that started this investigation, Dartford Council in Kent says it is currently “finding it extremely difficult to secure temporary accommodation within our own borough for emergency placements”, or “to provide private rented sector offers in order to discharge our homeless functions”, a spokesperson says.

“One of the many reasons for this is London authorities placing homeless households in Dartford, which in turn is putting increased pressure on our social housing allocations and means we have to use accommodation outside of our borough for this purpose.”

The council says using accommodation further afield has other impacts, such as increasing the numbers of legal review requests it has to deal with, as vulnerable applicants are challenging the suitability of offers if they need to be near existing support networks.

The council does not know precisely how many out-of-borough households have been placed in Dartford, as not all the placing councils notify it. This is despite legislation requiring them to do so, according to Dartford Council. The council is looking at ways of “escalating this matter in an attempt to create some transparency in terms of landlord details”, and to understand the true number and cost of the properties involved “so that the Kent authorities have the same opportunities of securing accommodation within our borough and [are] better [able to] assist our residents”.

Naushabah Khan, portfolio holder for housing and property at Medway, also says out-of-area placements have a “significant impact” in the area, as well as in other areas of Kent.

“Out-of-area placements reduce the number of homes on the market for local residents to access, drives up housing costs and places additional strain on local services, including schools and healthcare providers.”

She encouraged government to review the impact of out-of-area placements and “ensure that appropriate funding is allocated to councils which are adversely impacted by an increasing amount of vulnerable people being moved outside of areas they initially approached for support”.

None of the five councils sending the most households out of the capital responded to requests for comment.

Signe Gosmann, a researcher at charity Justlife, says numbers involved are “alarming” and “represent thousands of people, including children”.

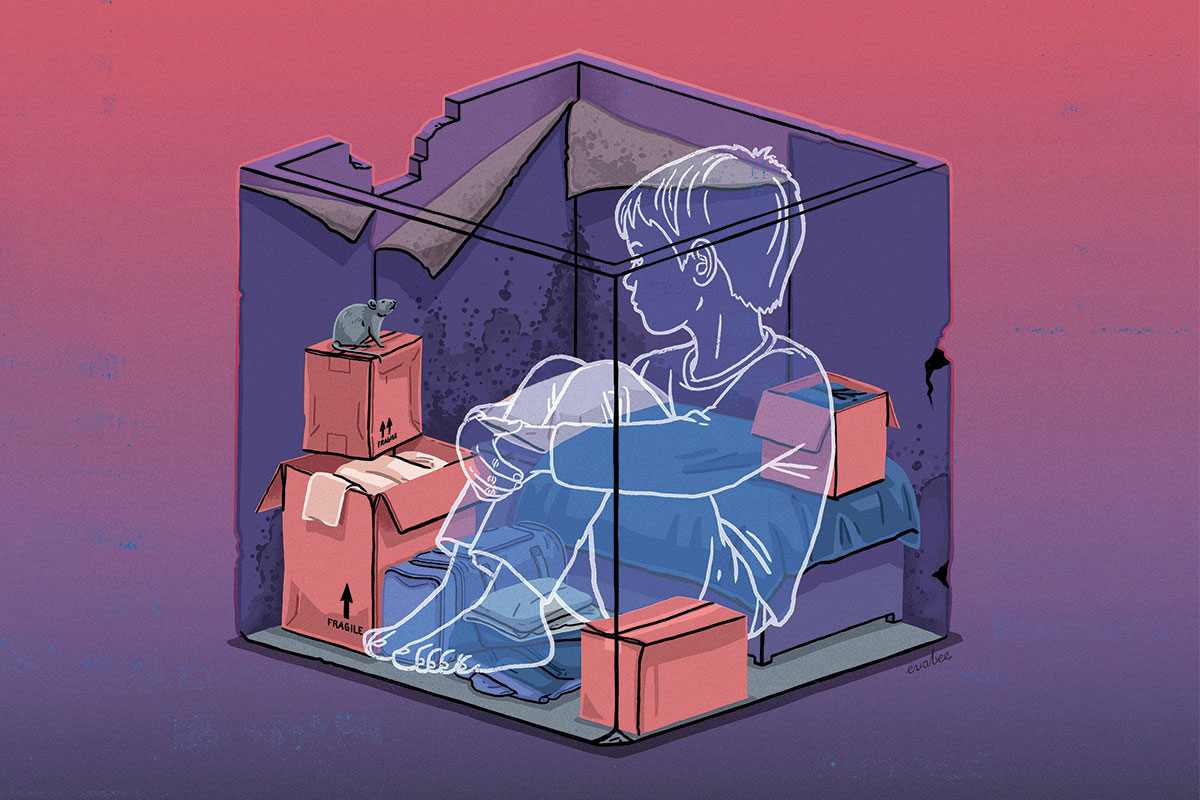

“Becoming homeless comes with its own challenges, but being placed far away from support networks, schools, GPs and community removes people from all the things that might help them feel safe and support them to rebuild their lives,” she says. “People are left lonely, isolated and struggling with their mental health, in an unfamiliar environment, with minimal support.”

“Becoming homeless comes with its own challenges, but being placed far away from support networks, schools, GPs and community removes people from all the things that might help them feel safe and support them to rebuild their lives”

Ms Gosmann says that “as a minimum practice”, councils placing people out of area should inform the receiving authority.

Over the past decade, the government has steadily reduced the amount of housing benefit people can claim. In 2013, it introduced an overall benefit cap, before freezing Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates – which can be used by private renters – in 2016. Before that, LHA covered the cheapest 30% of rents in the local area. LHA rates were restored to the cheapest 30th percentile in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, but they have been frozen since then and have not kept pace with inflation.

Meanwhile, private rents in London have soared. According to Rightmove, average monthly rent hit a record of £2,501 a month in the first three months of this year. Furthermore, recent London Councils research revealed that private rental listings in the capital have dropped by 41% since the pandemic. This all makes it ever harder for councils to find suitable accommodation for homeless households.

Slow pace of building

At a meeting of the APPG for London in July, Abigail Davies, director of Savills Housing Consultancy, said that private landlords are moving away from offering their properties up for temporary accommodation and homelessness prevention work.

Landlords themselves have reported that multiple factors are driving this behaviour, including increasing mortgage and operating costs, as well as anxiety around regulatory changes such as council licensing schemes and the proposed Renters’ Reform Bill, which could ban no-fault evictions.

The biggest obstacle when it comes to finding solutions is the slow pace of housebuilding. Despite recent comments by housing secretary Michael Gove that he “would like to see” 30,000 social homes built a year and newly announced reforms to the planning system, sector figures say that even this would not be enough to turn the tide.

Inside Housing’s Build Social campaign aims to get the main political parties in the UK to commit to a major programme of building homes for social rent in their manifestos at the next election. We are calling for them to commit to 90,000 homes a year in England, in line with research setting out that this is what is needed to meet housing need.

Indications are that out-of-area placements will rise further. Enfield Council recently announced a change in homelessness policy that will mean even more households are sent out of the capital.

A June council report outlining the policy cites rising rents, a lack of affordable housing, a falling supply of private rented homes available for use as temporary accommodation, and an increasing use of hotel accommodation – on which it is spending an “unsustainable” £850,000 per month. The change in approach means that the council is planning to start securing properties “further afield and to maximise choice for residents on these options”, the report says.

It adds: “Our primary focus will be on areas where rents are more closely aligned with Local Housing Allowance. For most residents in hotel and temporary accommodation this will mean relocating out of London and the South East of England.”

Meanwhile, Waltham Forest Council is awaiting the outcome of a case brought against it in the Court of Appeal over whether it breached the Equality Act when it rehoused a mother-of-three more than 100 miles away in Walsall, despite her family’s ties to east London.

Kevin Long, a solicitor at Hackney Community Law Centre, which brought the case, says it is one of “very many” the centre has been instructed on involving the suitability of out-of-borough offers of accommodation. “We had long argued that reliance on the benefit cap has a discriminatory effect as this impacts women more than men and the result is that single-parent households tend to only be considered for rehousing in areas very far from London.

“This is the point that now has been addressed by the Court of Appeal and whatever the outcome, it is likely to have important consequences for the way in which London councils deal with offers to rehouse homeless families.”

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities says it has given £2bn over three years to help local authorities tackle homelessness and rough sleeping, targeted to areas where it is needed most.

Nevertheless, councils insist that the situation is at crisis point. Mr Rodwell is calling for “emergency action at a national policy level to reverse the skyrocketing rates of homelessness”. He points out: “Boroughs do everything they can to find suitable accommodation for households in their local area, but the grim reality is that fewer and fewer options are available.”

*Redbridge Council’s data covers 1 March 2022 to 31 December 2022 only

Aims of our Build Social campaign

For all political parties to commit to funding a substantial programme of homes for social rent in their manifestos at the next general election. This includes:

● 90,000 social rented homes a year over the next decade in England.

● 7,700 social rented homes a year in Scotland.

● 4,000 social rented homes a year in Wales.

Inside Housing commits to:

● Work to amplify the voices of people who need social housing, including families living in temporary housing and overcrowded conditions.

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters