Homeless and on hold: the battle to get support from councils

Being threatened with homelessness is stressful enough. But, in some council areas, the process of getting support from the council is making things harder. Grainne Cuffe reports. Illustration by Peter Strain

Councils are in a temporary accommodation crisis. “I don’t think it is overdramatic, given the pressures facing councils, to tell the government that they are presiding over the end of local government if they fail to take the urgent action needed to finance it properly,” said Michael Jones, leader of Crawley Council. He was speaking in January at an emergency summit attended by more than 50 local leaders to discuss the “national crisis” of the cost of temporary accommodation.

Initial approaches to councils by people seeking homelessness assistance hit 311,990 last year – with nearly 300,000 owed a prevention or relief duty.

Hastings Borough Council nearly declared bankruptcy as its spend on temporary accommodation hit 49p in every £1.

The underlying issue of “not enough homes” is well known. But less talked about is the other side to this: how councils are coping with the requests for their help, and – when this is handled poorly – the impact on people facing a worrying and stressful life emergency.

One indication of this came last July, when from the stage at the Local Government Association conference, activist Kwajo Tweneboa described an experience he had with Lewisham Council. A resident reached out to him as they could not get through to the council after becoming homeless.

Mr Tweneboa tried and also failed to get through via phone and social media, so he went to the offices. There were no homelessness staff to see people who had dropped in. Their only avenue was to wait for a phone on site that was supposed to connect them with someone who could help. Lewisham refuted the length of the wait and said walk-in appointments are available for emergency cases. But the incident raises questions about what is happening in homelessness departments across the country.

Was this a one-off case, or a sign of a system fraying at the seams? Inside Housing launched an investigation in response. We wanted to find out how easy it is for someone facing homelessness to get help.

We sent Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to every English council, asking whether councils have staff on site at a local authority building to assess people dropping in who need homelessness assistance. Of the 223 that responded, 17% (38) can only be initially approached online or via the phone. Three said they sometimes offer the option of drop-in services.

Some of those are large city councils, including Newcastle, Manchester, Waltham Forest, Newham, Barking and Dagenham, Lewisham, and Havering. According to the latest government data, they collectively undertook more than 18,800 initial homelessness assessments in 2023 and owed a prevention or relief duty in nearly 18,300 cases.

Some councils said they do offer drop-in assistance if someone is vulnerable – but these claims did not always stand up to scrutiny. To understand the process, I visited some councils that lawyers and members of the public had raised concerns about. Arriving at offices or libraries, which purport to provide advice and assistance, I said I was enquiring on behalf of someone at risk of homelessness who was unable to use a phone or go online because of their mental health.

In Waltham Forest, I was shooed away by a member of staff in the housing assessment office upstairs, who looked irritated that I had knocked on the door. I went downstairs and was told by a staff member in customer service that initial approaches can only be made online or via phone, even after I repeatedly said the person was vulnerable and could not do that. “They’re going to have to find a friend or family to help,” he said.

Despite my experience, Waltham Forest – which only reintroduced face-to-face homelessness assessments in October 2023 following the pandemic – insisted that “we offer the option to drop into any council building” when I went to the press office for comment.

In Newham’s East Ham Library and Lewisham’s offices, I was told that the only way to apply for help was online or via phone. When I followed up with the press office, Lewisham said that this should not have happened and that “reception staff have been reminded of the process to ensure consistency in operational delivery”. Despite me explaining my experience at East Ham Library to Newham Council’s press office, it said it “works closely” with navigators there and “trains this team to help support residents making an application”. “They and other front-facing teams across the borough have access to our housing hub booking system should a resident want a face-to-face appointment,” a council spokesperson said. Its FOI response says it has two housing hubs with officers available to assess in person if a face-to-face appointment is needed.

But its website states: “Our HPAS [Homelessness Prevention and Advice Service] operates a limited appointment-only service from the housing hubs.”

When the press office was asked about this, it said: “Due to the size of the hubs, we do not advertise them as ‘drop-in’, but residents who approach will be seen on a drop-in basis if their situation is urgent, otherwise a suitable appointment is booked.”

For ethical reasons, I did not pretend to be homeless, but if I had, I might have had a different experience.

Liverpool City Council does not even have an online form, just a telephone line for initial contact. Housing solicitor Siobhan Taylor-Ward, from Vauxhall Community Law & Information Centre, has been working in Liverpool. She says it is a “major issue”, leaving “many people on a constant merry-go-round of being told to await a call back while not receiving the help they need”.

She says: “In so many of our cases, it is not until a threat of judicial review is issued that people are given the help they are entitled to.”

A council spokesperson said the online referral form is no longer in use “as a result of a review of our housing options service” but that “work is ongoing to ensure the council has a fit-for-purpose self-referral form back on our website as soon as possible”.

They said capacity within the contact centre has “also been increased in order to take telephone referrals and ongoing enquiries”.

Simon Mullings, former co-chair of the Housing Law Practitioners’ Association, says he thinks the issue is widespread. “[Councils will] often turn people away from the offices where you’re supposed to apply and say, ‘No, you need to ring the number,’” he says, a line on which you “could be on hold for hours and hours”.

311,990

Initial approaches to councils by people seeking homelessness assistance last year

£2bn

Amount councils’ recorded spend on temporary accommodation is expected to reach this year

49p

Spend on temporary accommodation in every £1 by Hastings Borough Council

Difficulties in making contact with the homelessness team at a council are no small matter for people who are in this position, as one person who has gone through the process explains to me.

It is a freezing day in January and Ava (not her real name) has just been evicted from Home Office accommodation with two weeks’ notice. With no job, the private rented sector is not an option. She fills out a form seeking homelessness assistance from her local council. Two weeks later, it is eviction day, and Ava has had no contact since then. She can only hope that the local council will contact her so her family will have somewhere to stay that night.

The family has already been through a lot. Ava, her young daughter and her husband sought asylum in England after fleeing a war-torn country in 2022. “We were coming home from my husband’s parents’ home one day and the car in front of us was bombed. They would just bomb randomly,” she tells me.

This council – which we are anonymising to protect Ava’s identity – has a system that means initial approaches for homelessness assistance are online or via the phone. Ava is lucky that her husband is proficient in English, so they could fill out the form. At around 4pm on her eviction day, Ava finally receives a message from the council with an address. It is far away, out of London. Ava has 10 bags, a young child, and no way to get there. The council offers no transport.

Pressurised system

The homelessness code of guidance for councils sets out how they should exercise their duties under the Homelessness Reduction Act. Councils will “need to provide access to advice and assistance at all times during normal office hours, and have arrangements in place for 24-hour emergency cover”.

Applications can be made to “any department of the local authority and expressed in any particular form”.

“So, if someone went to the council’s offices and said they were threatened with homelessness, that is an application, regardless of the council’s policy,” explains Giles Peaker, partner at law firm Anthony Gold.

The guidance also says that housing authorities should provide assessment services that are “flexible” to the applicant’s needs.

Barrister Justin Bates says it is “lawful” to use online forms and phone calls “as part of a scheme”, but warned councils to “think about hard cases”, such as domestic abuse victims, disabled people, or those with mental health issues.

Homelessness charity Crisis runs seven services in England, which work with people experiencing homelessness. These include practical support to help people access benefits, healthcare services and employment opportunities. Five of these report that councils have cut back delivery of services in-person. Francesca Albanese, executive director of policy and social change at the charity, says this is “definitely” having an impact on vulnerable people and “puts extra pressure on voluntary services”.

“Part of our service is to support vulnerable people to challenge decisions. What we’re seeing is the lack of face-to-face services means that people are getting inappropriate advice and information,” she says.

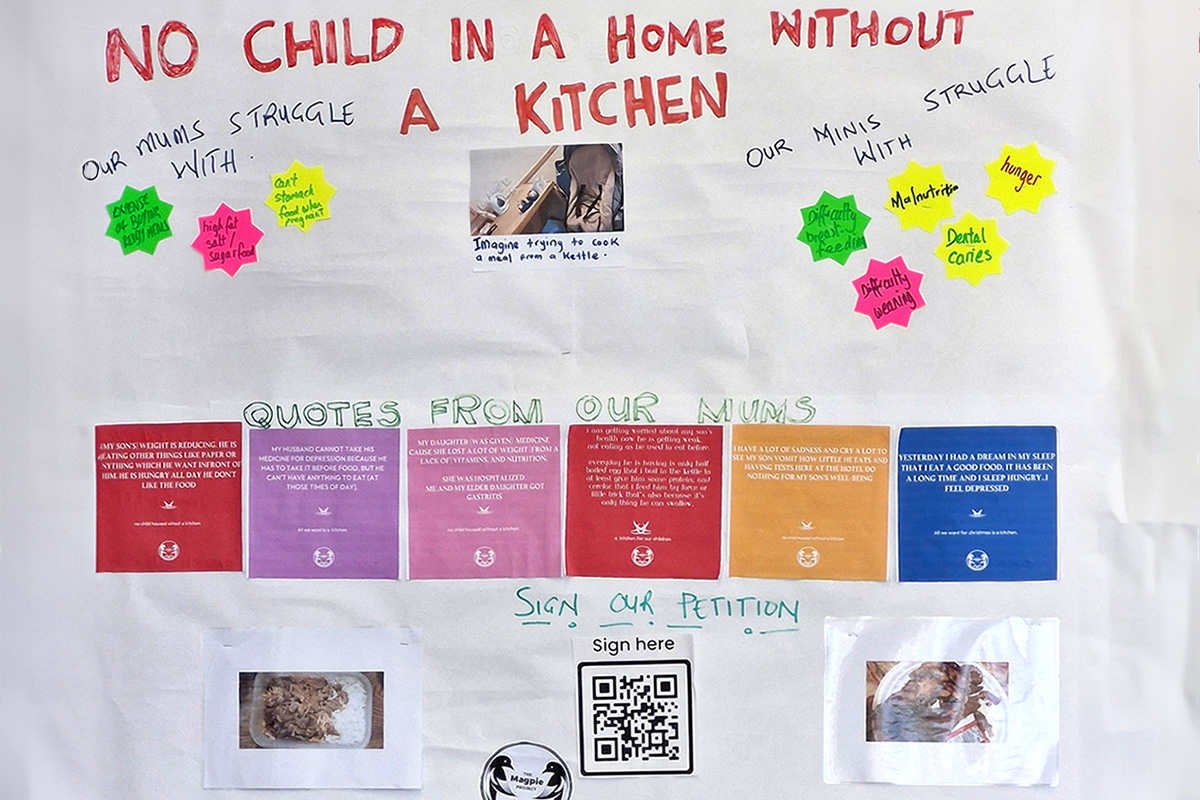

In Newham, The Magpie Project is a charity that supports mothers who are seeking asylum or have refugee status. When someone is granted asylum or leave to remain, The Magpie Project tells them what they need to do next to navigate the homelessness system, and also helps with HPAS applications through a volunteer form-filling service.

Jane Williams, founder and chief executive of The Magpie Project, says: “We have to support this process because our families are in digital poverty, and do not have English as a first language. The homelessness forms in Newham are extremely complex, they don’t save and they can time out if it takes too long to fill them in. After the HPAS has been filled in, there can often be multiple requests to upload the same documents over and over.”

When we ask Newham about this, it says it reduced the online form by 50% last year, adding that it is “among the briefest to complete in London and, unlike many authorities, does not require an account to be made prior to completion”.

After sending the form, families get a reference number and should get an email from a housing officer.

“Newham says they aim to speak to all applicants within five working days of the application. This rarely happens,” Ms Williams says.

There is no longer a phone number on the Newham HPAS website, only one for the customer contact centre, which the website says “will be able to pass a message on to HPAS”. The website advises against ringing the number unless someone is unable to use email or does not have a computer.

“Sometimes contact does not come until the day of eviction, or at all unprompted. The amount of stress and trauma this creates is something that our family support workers find it difficult to help journey through. Sometimes families with small children do not get to their new – sometimes unfurnished – accommodation until after 8 or 9pm,” Ms Williams says.

Newham says it would like to be able to identify accommodation and book it in advance of a household becoming homeless, but adds: “Due to the extreme pressures from demand and severely reduced supply of accommodation, along with sometimes very short notice of households becoming homeless, we often have to source accommodation on the day.”

Some changes that could make things better for families facing homelessness, though, are more about the process of applying. The Magpie Project wants to see savable HPAS forms introduced, a clear process map of how the homelessness system works with timescales, and some easily accessible face-to-face provision.

It would like to see a housing officer able to take families through the whole process on the day rather than a change of three professionals (housing officer, procurement officer, housing manager).

Problems with digital access

So why is this not happening? Funding is one obvious contender. Ms Williams stresses that her charity “recognises that the issues of demand and capacity faced by the housing department in Newham are extreme even compared with other London boroughs”.

She also says that the charity works alongside Newham through a monthly meeting and as members of the Newham Temporary Accommodation Action Group to raise and resolve the issues that families face around housing and homelessness. And as Newham Council highlighted, it receives one of the highest numbers of homelessness applications in London.

Inside Housing understands that some councils reviewed their processes after services were forced online during the pandemic and concluded that digital-first would be more efficient. One says that, pre-pandemic, people criticised lengthy wait times for those dropping in without pre-contact, which diverted resources from emergency cases. Another says that the majority of residents “prefer the flexibility that remote assessments can offer”.

Mr Mullings says that, for some council services, online-first is a good thing. “But homelessness is an area where you can’t really do that, because by definition you’re working with an almost exclusively vulnerable group of people,” he says. “They very often need face-to-face services in order to get across what their situation is and very often need urgent help. So sending people away to call a not-properly-managed telephone number is just not appropriate.”

Mr Tweneboa is firm that the status quo is not good enough. “These people are desperate and anxious,” he says. “They’re at the worst point in their lives because they don’t know where they’re going to sleep at night.

“Yet councils have decided it’s acceptable that they have to sit on a phone and hope that they get through to someone that actually wants to help them. And in many cases, that’s not the case. They don’t get that help and people end up on the street. It’s a dereliction of duty.”

Everyone Inside Housing spoke to acknowledged that councils are under huge pressure, with an expected temporary accommodation bill of £2bn this year, while dealing with added demand from the government fast-tracking asylum claims.

London Councils, the collective body for local authorities in the capital, says that boroughs are “committed to providing the best possible support” for homeless Londoners “despite continued pressures on their resources” and that they “take their legal duties very seriously, which includes ensuring that services are accessible”.

Islington Council has decided to prioritise face-to-face assessments for drop-in cases. Staff at its centre were helpful and welcoming. Una O’Halloran, cabinet member for housing, says: “I just couldn’t bear it that people have to go on phones in queues.” She understands there is a cost issue, but is trying to convince other councils to do the same. “We have an open-door approach. If your English isn’t good, you’re not IT literate, if you’re older, if you can’t read and write – if you turn up somewhere and someone treats you like a human being, that’s a start, isn’t it?”

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities says our findings are “concerning”. A spokesperson says: “We expect local authorities to offer face-to-face homelessness support when people request it, or if it is clearly necessary.”

Newham says it needs the government to “seriously address the root causes of the housing crisis”, as well as greater powers and funding to deliver social homes, more support for homelessness prevention, and Local Housing Allowance rates to be uprated annually.

As for Ava, on the day of her eviction, a charity helped transport her and her family to emergency accommodation, where they have been since January. She has heard nothing from the council. It should have notified her within 56 days whether it owes her a relief duty. She rings and emails, but cannot get through. Even if she could get in-person help, a train ticket costs more than £50. “I just feel they have thrown me here and forgotten me,” she says.

Recent longform articles by Grainne Cuffe

The first year of tenant satisfaction measures: the results

Government overhauled consumer regulation following Grenfell. Now, an Inside Housing survey of more than 200 councils and housing associations reveals the first results from the new TSMs regime. Grainne Cuffe investigates

Awaab’s Law: how it could challenge and change the sector

The consultation is out for Awaab’s Law, setting time limits for English social landlords on responding to repairs that pose a hazard to tenants. But what exactly is in the proposals? Grainne Cuffe reports

Homeless and on hold: the battle to get support from councils

Being threatened with homelessness is stressful enough. But, in some council areas, the process of getting support from the council is making things harder. Grainne Cuffe reports

Housing officers under pressure

Grainne Cuffe talks to housing officers about the stress of their jobs, as Inside Housing reveals that turnover in some frontline roles has risen dramatically

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters