You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Grenfell Tower Inquiry phase two preview: what was known about cladding in central government

Ahead of the start of phase two of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry on 27 January, Inside Housing is previewing some of the issues that will be under consideration. In the first of these, Peter Apps looks at the difficult questions central government may have to answer. Picture by Getty

“I shall also examine what was and should have been known, both by those in the construction industry and by those in central government responsible for setting fire safety standards, about the particular dangers posed by thermoplastic polymers.”

This is a statement by Sir Martin Moore-Bick, the retired judge who chairs the inquiry, from his phase one report. He makes it clear that he will interrogate government’s role in setting fire safety standards in relation to cladding. This is likely to have sent a few shivers through Whitehall and Westminster.

The cladding system in use on Grenfell Tower comprised aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding with a polyethylene core produced by giant American metals company Arconic, combustible polyisocyanurate plastic insulation made by Celotex, and a smaller amount of combustible phenolic foam made by Kingspan.

The first phase of the inquiry ruled that this system did not comply with the headline requirement of building regulations that the walls of a building must “adequately resist the spread of fire”. But this does not get government off the hook.

To supplement this headline recommendation, officials published guidance – Approved Document B – that explains how to achieve this standard. This guide is treated by many in the industry as a prescriptive set of minimum standards – which makes what it had to say about cladding highly significant.

Over the years, several warnings about the danger of cladding fires in high rises have been issued.

“We do not believe that it should take a serious fire in which many people are killed before all reasonable steps are taken towards minimising the risks”

These date back as far as 1986, when a bulletin issued by the Department for the Environment, at the time responsible for building regulations, warned of the risks of a cladding fire in a system using aluminium panels.

It said: “Laboratory tests have shown that a fire within the cavity can melt the aluminium and burn through to the surface several storeys above the fire. These emergent flames could re-enter the block via windows.”

These warnings ratcheted up in the 1990s, with two fires at the start and end of the decade demonstrating the very real danger of attaching combustible plastic to the walls of tower blocks.

At Knowsley Heights in Merseyside, flames ripped through a rainscreen system after arson in a bin outside the tower in 1991. And then in 1999, flames tore up the outside of a tower block in Irving, Scotland, via a strip of combustible window panels.

As a result of these two fires, a parliamentary select committee launched an inquiry into the dangers of cladding fires generally. This inquiry made a number of important points when it released its report in June 2000.

First, it made a clear statement that while a disaster may not be imminent, action was needed to prevent one. Specifically, it said: “We do not believe that it should take a serious fire in which many people are killed before all reasonable steps are taken towards minimising the risks.”

The main recommendation as a result was the introduction of “large-scale testing” as a way to deem whether cladding systems were safe. As Inside Housing explained in 2018, this kicked off the process that – somewhat perversely – led to an explosion in the amount of combustible insulation on high rises.

But there was more to the select committee report than a recommendation for testing. First, it said social landlords should be tasked with establishing their number of buildings with cladding systems and call in “competent fire risk assessors… to evaluate what work may be necessary to ensure that no undue risk is posed”. It was also recommended that they be instructed to “monitor existing cladding systems carefully” to ensure the fire risk did not increase. Neither was done.

More specifically, the committee heard evidence that the official guidance, Approved Document B, was inadequate. A cladding system like the one that would eventually be used on Grenfell comprised two key materials: insulation boards and external cladding. The insulation is fixed directly to the walls to keep the building warm. The cladding is fixed in front of the insulation to keep it dry, and forms the external surface of the system.

The committee found that while there was a tough standard in place for insulation (limited combustibility, which essentially banned anything flammable), the standard for the cladding panels was the much lower rating of ‘Class 0’.

Serious concerns were raised by an expert witness about this Class 0 standard, which was said to “undermine the integrity of the regulations” as it referred only to the surface of the material. This meant combustible products could sneak through if they had a non-combustible facing or were packed with fire-retardant chemicals. As such, the committee recommended a tightening of the regulations to ditch the Class 0 standard and to ensure instead that all cladding products were entirely non-combustible. This was never done.

Grenfell Tower Inquiry phase two: modules

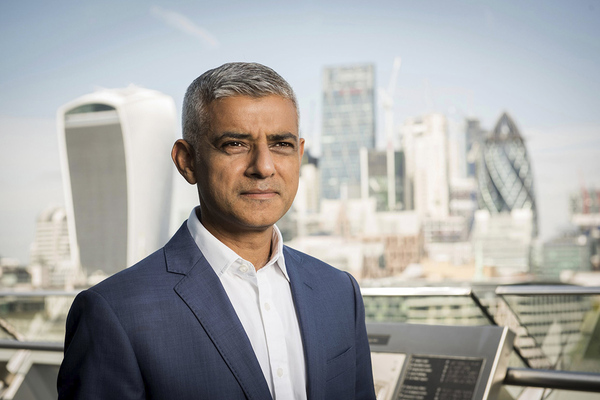

Inquiry chair Sir Martin Moore-Bick (picture: Getty)

The second phase of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry will be split into eight separate modules. Hearings will begin on Monday 27 January with the first module called ‘The primary refurbishment (overview and cladding)’.

This will include an examination of the decision to carry out the refurbishment and its budget, as well as the procurement of Rydon to act as the ‘design-and-build’ contractor for the job.

The selection of the materials in the cladding system, their compliance with the regulations and the process of building control will also come under the spotlight.

The inquiry will then move on to the testing, certification and marketing of the cladding products used.

Other modules will include active and passive fire prevention features of the tower – such as fire doors, lifts and the smoke control system, the role of central government and further evidence about the preparedness of the fire service.

Moving forward, the next major warning for central government came in 2009 when flames ripped through combustible high-pressure laminate window panels on the walls of Lakanal House in south London, killing six residents.

Four years after this fire, in 2013, a coroner’s inquest resulted in a series of recommendations to ensure no repeat of the disaster. We have analysed in detail how well these were followed here and here – an issue that will doubtless be of major interest to the inquiry.

“The first real indication of problems came from buildings catching fire overseas and people realising the same material was present on all of them”

On the specific question of the danger from cladding, though, the Lakanal inquest resulted in a finding from the jury that the panels had not met the ‘Class 0’ requirement, as required by guidance. But the jurors warned that even if they had met this standard, the fire would still have spread. This should have served as a warning that the Class 0 standard was not tough enough.

But despite the persistent lobbying of experts and MPs engaged in the fire safety debate, the standard was not toughened in the years that followed.

Fears about cladding fires mounted in the first half of the 2010s, and a number of fires around the world revealed the potential danger from a flammable facade – particularly one comprising ACM cladding.

“The first real indication of problems came from buildings catching fire overseas and people realising the same material was present on all of them,” says one industry source. “Certainly by 2014, it was something we [in the industry] were discussing.”

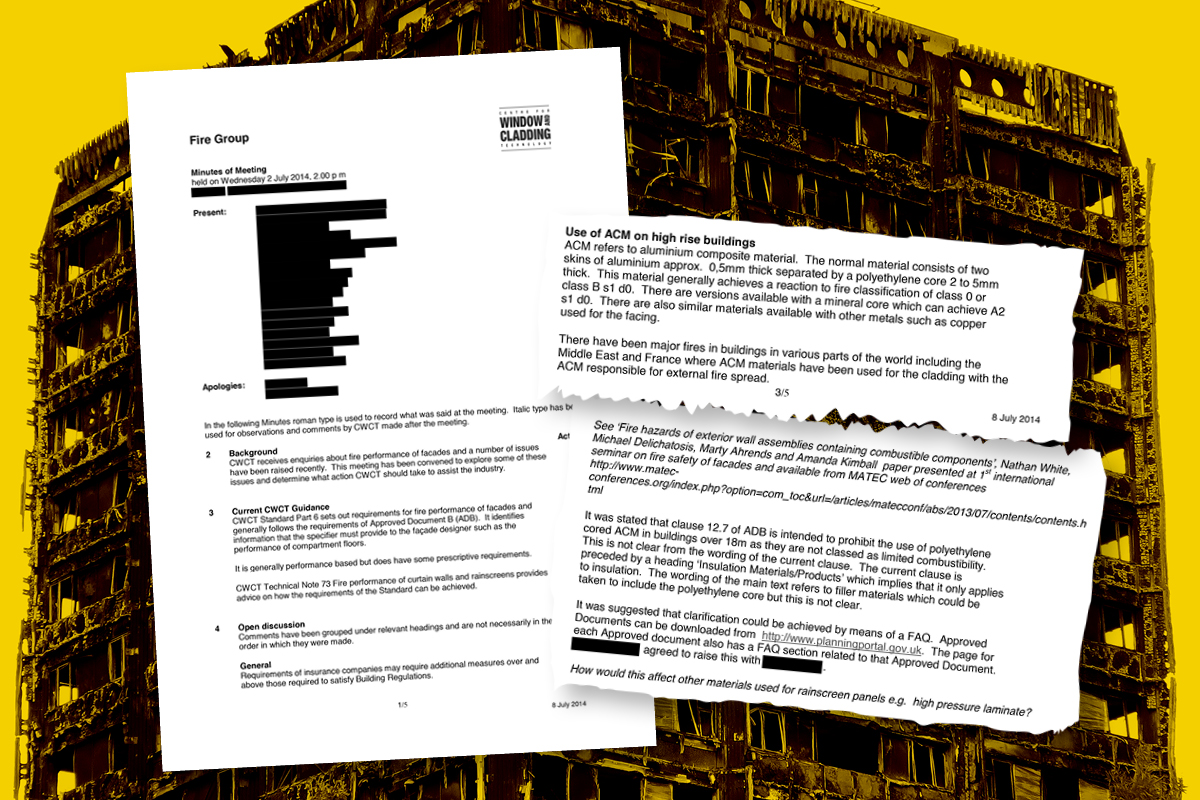

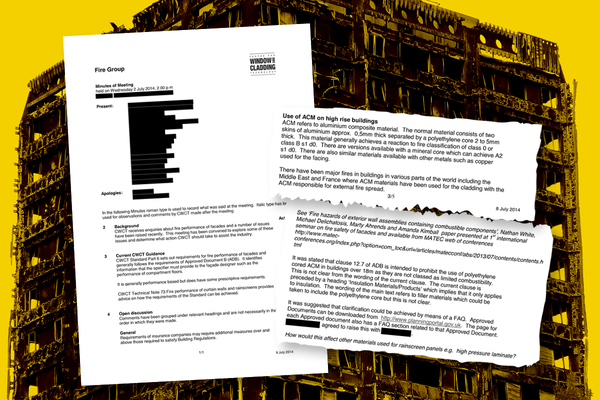

The minutes of the CWCT meeting, obtained by Inside Housing (picture: Getty)

The discussion reached government. In 2014, at a meeting of industry representatives and officials, senior civil servants were very specifically warned that the ‘Class 0’ standard in building guidance was resulting in the use of ACM cladding with a polyethylene core – the same that had been linked to fires overseas and the exact material that would later be used on Grenfell.

While the officials claimed at the meeting that this material should not be used under the guidance, they were warned that this was not clear from the guidance and were encouraged to publish a “frequently asked question” to confirm it should not be installed. This was never done either.

In the event, the ACM used on Grenfell had a certificate rating it as Class 0 – although there are some important questions about whether or not it deserved this rating.

The government has not engaged with these questions up until now, claiming that its guidance should have been interpreted in a way that would make ‘limited combustibility’ the correct standard for cladding panels as well as insulation.

This argument is likely to be explored in detail when ministers and officials give evidence in the second phase of the inquiry. One, Gavin Barwell, who missed repeated warnings as housing minister, has already confirmed his likely attendance.

While this argument about Class 0 is pertinent to the debate about the widespread use of ACM cladding, it does not explain why combustible insulation was used on the tower – when the basic standard was ‘limited combustibility’. This issue will be explored in more detail in tomorrow’s preview.

Generally, though, officials should expect to be asked why, despite fires overseas and in the UK, more was not done to control and identify the use of dangerous cladding systems in the UK.

Part of the reason may be the government’s decision to impose a ‘one in, two out’ rule on new regulations from 2012 onwards, which would have curtailed the power to set tougher standards for industry. If the inquiry finds the time to get into this issue, it could suddenly find an entire political system in its sights.

A Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government spokesperson said: “We remain committed to understanding the causes of the fire at Grenfell Tower and to learning the lessons needed to make sure a tragedy like this never happens again.

“We are ready to assist the inquiry in whatever way we can during phase two.”

Grenfell Tower Inquiry phase two previews

Picture: Getty

Inside Housing published a series of preview articles ahead of the start of Phase Two of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry on Monday 27 January. You can read them here:

What was known in central government about cladding?

What did officials know about the dangers of fire from combustible cladding, and did they act on the warnings?

Click here to read the full story

The testing and certification of materials

What tests and certificates existed for the materials used in the cladding system on Grenfell Tower, and was the system that provided them fit for purpose?

Click here to read the full story

The decision to install the cladding

Who decided to install polyethylene-cored ACM cladding on Grenfell Tower and why?

Click here to read the full story

The fire doors and windows

What went wrong with the fire doors and window installed at the tower?

Click here to read the full story

The warnings of the local community

What did residents say before the fire and why were they ignored?

Click here to read the full story

Over the course of the inquiry, Inside Housing will publish regular news updates on its progress and a weekly round-up of the key evidence and its significance for the social housing sector every Friday afternoon.

Grenfell Inquiry: what will be investigated in phase two

Picture: Rex Features

The deceased

Sir Martin originally hoped he would be able to publish findings on the circumstances in which the deceased met their deaths as part of phase one. This has now been pushed to phase two as it requires “more detailed examination of the evidence that has been yet been possible”.

The London Fire Brigade

A further investigation will be made into the London Fire Brigade (LFB) as an organisation, following the failures of response identified in phase one of the report. This will include questions over training and a greater scrutiny of those at the top.

Testing and certification of materials

Questions over how Grenfell came to be covered in highly combustible materials will “lie at the heart” of phase two. This will involve looking into the adequacy of regulations, the effectiveness of the tests currently in use and the manner in which materials are marketed.

Design and choice of materials

The 2016 refurbishment of the Grenfell Tower will be under the spotlight in phase two, with questions being asked about why aluminium composite material (ACM) panels and combustible insulations was chosen. This will include an examination of the government’s building regulations.

Fire doors

Following the concerns raised over fire doors as part of phase one, phase two will look further into whether these doors complied with regulations, whether they were able to provide appropriate protections against fire and smoke and if not, how that situation came about and why.

Window arrangements

Phase one found the use of uPVC window jambs in close proximity to combustible insulation allowed the fire to initially escape the flat in which it began. Decisions made over windows as part of the 2016 refurbishment will also be explored in phase two.

Lifts

It appears that the ‘fireman’s switches’, which should allow firefighters to take control of a lift, were not working on the night of Grenfell, leading to fatal consequences. Phase two will investigate whether the lifts in Grenfell were properly maintained.

Smoke extraction system

An investigation will be carried out into suggestions, made as part of phase one, that the smoke extraction system failed to operate in accordance with its design and potentially contributed to the spread of smoke between different floors.

Local community warnings and the authorities’ response to Grenfell

Phase two will delve more into accusations that local community warnings over fire safety and the refurbishment were ignored by the tenant management organisation. It will also scrutinise the authorities response to the disaster in the immediate aftermath.