You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Filling the void

Helena Partnerships was faced with a glut of three bedroom homes it couldn’t rent. So it turned to the private rental market for answers. Jess McCabe reports

In the more bustling cities of Britain, social landlords view the private rented sector as a means to make some cash.

The Merseyside town of St Helens is not, at first glance, the most obvious location for such a commercial experiment.

Glass making and manufacturing once made this town rich, but have long since tailed off. Although its economic fortunes have improved in the past few years, it is still the 51st most deprived local authority in England. In some areas social rents are higher than market rents.

Yet the area’s biggest social landlord, the 14,000-home Helena Partnerships, has managed to dramatically cut the number of empty homes on its estates - by renting them privately.

It was 1 April 2013, the date on which the bedroom tax came into effect, when Helena’s problem with voids suddenly escalated. ‘It was immediate,’ recalls Gill Healey, director of Helena’s extra care services.

Before the reforms, Helena typically had fewer than 100 empty properties at any one time classed as ‘management voids’ that it was actively seeking to let, according to Tom Bate, voids partnership manager at Helena.

By August, just months after the bedroom tax came in, Helena had 298 management voids. The reason? Helena had too many three-bedroom homes, and not enough demand to fill them.

Common experience

Helena is far from alone in experiencing this phenomena. Charlotte Harrison, executive director of the Northern Housing Consortium, says that many of its members have reported a rise in voids and concern about longer re-let times.

‘Members report that this can be down to very local market dynamics; the impact of welfare reform changes, particularly the under-occupation charge; and the quality and responsiveness of the private rented sector,’ she adds.

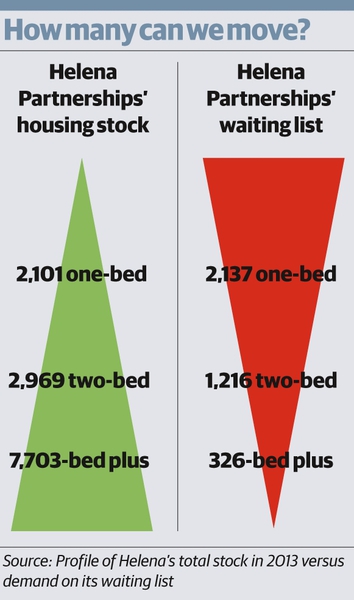

But even before the bedroom tax, Helena’s three-bedroom problem was waiting to happen. The landlord had 7,703 homes with three bedrooms or more, twice its stock of one and two-bedroom homes.

With more than 1,000 tenants leaving in any given year, demand for these homes was already well below supply - between 65% and 75% of Helena’s annual vacancies for homes are typically for three-bedroom homes. On

its waiting list, only 326 families were looking to move into a three-bedroom home. And then with the welfare reforms, under-occupying tenants started moving out because the full cost of their rent was no longer covered by housing benefit.

It wasn’t only the bedroom tax that was having an effect. ‘We’ve got an ageing population in St Helens, so a lot of our tenants are older people. On one hand, they’re not affected by the bedroom tax. But a lot of those older people live in three-bedroom houses, and they die, and a significant number of the voids that came through were as a result of that. So it’s not just one factor you’re dealing with, you’re trying to stem the tide [of voids created] by various issues,’ Ms Healey says.

Helena staff were worried - empty homes could easily become a crisis. ‘Four Acre is an example. We had about 30 empty properties on an estate that’s got about 800 of our stock,’ explains Gaynor Johnson, head of neighbourhoods.

‘And when you start seeing the impact of that on the community, when you’ve got properties empty, we were really keen on trying to stem them [the rise in vacant properties] as soon as possible. We’d done an awful lot of work to stabilise those communities and we were really worried that we’d start getting blights. And the more empty properties, the less people want to live on those estates,’ adds Ms Healey.

This might sound like an almost insurmountable problem. But today, Helena has only 119 management voids, only a few more than before the bedroom tax, along with another 54 it is refurbishing.

It has accomplished this feat by renting out some of these voids to private tenants at a mix of social and affordable rents, depending on the prevailing market for PRS homes on particular estates.

The idea came from a mass meeting of Helena’s staff that was called as the welfare reforms started to bite. Helena brought together 250 of its housing staff to come up with ideas as to how the housing association could rescue itself from the financial strain of the welfare reform.

Out of this meeting came 16 projects - which Helena calls its ‘sweet 16’ - to help the organisation out of its welfare reform-induced problems. One of the projects, ‘new markets’, involved taking voids that Helena couldn’t let out, mostly three-bedroom properties, and renting them to private tenants.

New markets

The target market were people who ‘traditionally wouldn’t have thought they stood a chance of getting social housing’, Ms Healey explains. Helena also searched its waiting list to find potential tenants who wouldn’t normally qualify under the allocation rules for a three-bedroom property but could afford the rent.

‘I was one of them myself,’ chimes in Helena press officer Robert Doyle. ‘I was caught in just that trap - a broken marriage behind me, couldn’t afford to buy anywhere, couldn’t afford to rent in Liverpool for what I wanted, because I wanted my children to stay and so on. So welfare reform was the best thing that ever happened to me because all of a sudden I was eligible to rent a lovely flat close to work.’

Helena is a stock transfer housing association and under its agreement with the council it must make available 75% of its stock to nominations from the council’s waiting list. But it had never actually used its freedom to allocate the remaining 25%. Last year, it started to allocate some of them to its ‘new markets’ tenants.

‘Initially they were really good properties, prime properties in prime areas, [so it was easy] to say come and have a look - whatever you thought about social housing before, whatever you thought about our estates before, come and look at this product because it will knock your socks off,’ explains Mr Bate. ‘That encouraged a lot of people to express interest.’ Slowly the association started to add properties from its mainstream estates.

The association has encountered surprises along the way. The association thought it would have to pull out all the stops when decorating for new markets tenants. But Helena found private tenants prefer to do much of the work themselves: even putting in their own kitchens, which has kept the costs of the scheme to a minimum.

Staff have also been taking referrals from unlikely sources. For example, the council was wary of younger tenants being unable to sustain their tenancies, and asked Helena to interview all potential tenants under 24 years old. But it emerged some of the young people were in work and could afford a three-bedroom home, and they were referred to the ‘new markets’ team.

Helena used private letting website Rightmove to research the market, checking the condition and rental costs for some of its own former properties that were bought under the right to buy and were being let out. But given the realities of St Helen’s rental market, the partnership developed a rather different approach to PRS to that of the average private landlord. So far the initiative has brought in £460,000 in rental income.

New markets tenants are not charged higher rents - this would hardly be feasible when social rents are often higher than the traditional PRS - and they receive the same type of secure tenancy as other tenants. ‘We looked at market rents, but the big driver against that is our charitable status and the need for approvals from the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA). We were going to meet with the HCA, but meetings got postponed, so we stuck with the affordable rents,’ Mr Bate explains.

In total, 42 of the new markets tenants in the more affluent areas of St Helens are on affordable rents - charged at 80% of market rent, which averages £10 a week more than the social rent would be. The remaining 122 new market tenants are paying social rents, regardless of whether they are lower or higher than market rent for similar properties in the area. The average social rent is £90.26 a week.

The landlord benefits because its new market tenants tend to need fewer resources in general than those who have been assigned on housing need. They tend to phone in less often, preferring to pay rent and interact with their landlord online, and as they are often employed they put less of a strain on Helena’s resources.

Chimi Shakohoxha, a partner at law firm Clarke Willmott, says that as long as social landlords set private rents at or below social rents, social landlords shouldn’t have to jump through legal hoops before going ahead with initiatives such as this. This is because landlords will still be renting to people on a low income, and so fulfilling their charitable purpose.

‘If you are a secretary in Liverpool [you’re probably earning] £14,000 to £15,000. As such, you may not consider you are qualified for the [housing] list,’ he notes. ‘That’s how I calculate it, what a secretary gets paid.’

Helena is quick to point out that the private tenants make up only a very small proportion of its tenants, with only 164 new markets tenants to date. ‘Doing this isn’t contrary to our purpose, it supports our purpose,’ adds Debbie Trust-Dickenson, director of customer experience at Helena. ‘If the voids continued to go like [they were], that would be at the cost of a frontline service,’ Ms Healey adds.

Following suit

Whether other landlords could follow suit is a different question. The success of the scheme seems to hinge on the market conditions of St Helens. And Ms Harrison from the National Housing Federation points out that for some northern social landlords, the issue of voids is becoming less urgent. ‘Some members are now suggesting [void levels] have “peaked” and they are seeing these levels reduce,’ she adds.

‘That said, we are aware that members remain concerned about both short and medium-term impacts on demand. They [are] looking at how they can stimulate this locally from initiatives such as the Helena Partnerships to advertising properties on mainstream property websites such as Rightmove and undertaking research into the dynamics of their private rented sector, and understanding perceptions around social housing as an option for those considering low-cost home ownership.’

For now, the reduction in voids suggests the approach is a success. ‘I’m working my way out of existence at a rate of knots,’ says voids manager Mr Bate.