You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Disabled tenants speak out through new charter

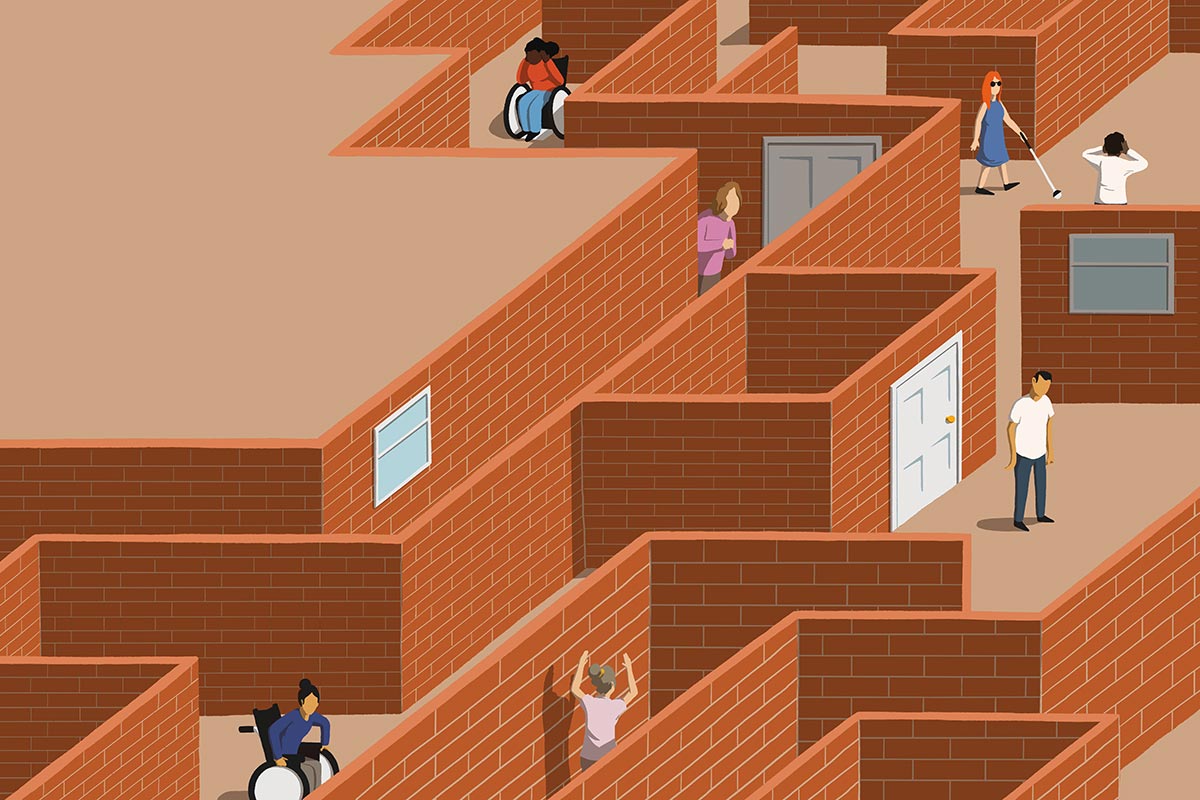

A new charter aims to improve how social landlords interact with and make accommodations for disabled tenants. Philippa Willitts talks to some of those involved, and other disabled tenants, to find out why it is needed. Illustration by Andy Carter

Disabled tenants have created a new charter in the hopes of helping social landlords improve how they interact with them and ensure they are complying with the disabilities part of the Equality Act.

A year since the launch of the Social Landlord Disability Charter Scheme, Inside Housing wanted to find out more about the charter, why it was created, and what lessons social landlords can draw from it.

Created by the Social Housing Action Campaign’s (SHAC) Disability Visibility Group (DVG), the charter sets out the benefits of raising awareness about disability and wants to improve relationships between social landlords and disabled tenants. It calls for landlords to comply with equality legislation and aims to eliminate discrimination and advance equality.

Social landlords that adopt the charter will sign up to implement a person-centred approach on mental health provision, as recommended by the Care Quality Commission (CQC).

They will also agree to be inspected by the CQC and externally monitored to ensure they comply with the Equality Act and their own internal diversity and inclusion policies.

But why is the charter necessary, and what has led to its creation? While many people think that the main problem disabled people face with housing is physical access, this charter has a particular focus on tenants with mental health problems or neurodiversity.

It began with a blog post, in which Carl* wrote about his frustrations with how social landlords deal with disabled tenants. This resonated with so many people that the DVG was set up and the creation of the Social Landlord Disability Charter Scheme followed.

Social Housing Action Campaign

SHAC is a tenant and activist network. It launched the DVG when it heard reports that tenants who were disabled were being poorly treated, particularly neurodiverse people, those with mental health problems and people with invisible impairments. The charter came out of their experiences, hopes and needs.

Other disabled tenants Inside Housing speaks to have similar stories. Ali* fled domestic violence with his son, Mohammed*, in 2019. After a period of homelessness, they were allocated a home earlier this year in London that was meant to be accessible. In their previous property, Ali had to carry his disabled son up two flights of stairs. Mohammed would frequently fall down those stairs during seizures.

However, there have been ongoing problems with installing the adaptations Mohammed needs in their new home, as well as hazards in the garden, anti-social behaviour, and a bathroom with a bath rather than a wetroom. This means that not only does Ali still have to wash his 11-year-old son over the bath, rather than him showering independently, but also that Ali has to lift Mohammed in and out of the bath, even though Ali has had major surgery. There are handrails, but they are rusted and too far apart for Mohammed.

As a member of the London Renter’s Union, Ali feels confident that he knows the right things to say to his landlord, but his own autism and ADHD can mean his communication style is misinterpreted.

“The fact of the matter is, I have a lot of energy and a lot of time on my hands because I’m a full-time carer,” Ali says. “If me making all this noise is still not getting results, then what about all those people who don’t have a loud mouth like me?”

Carl, who wrote the blog post that sparked the charter, explains that he has a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia and had requested his housing association to give advance notice of visits to his home.

Having contractors in his home unexpectedly caused Carl to become unwell and he was hospitalised several times. Yet despite his requests, somebody unexpectedly arrived to carry out a repair in his home the day before he spoke to Inside Housing.

Problematic assumption

Activists say there can be an assumption among social landlords that if somebody has mental health problems, they are automatically a ‘problem tenant’. This is damaging and leads some tenants to think that any poor treatment they receive is a result of their openness about their diagnosis.

Suzanne Muna, secretary of SHAC, says that disabled social housing tenants are getting a poor deal and that SHAC is keen to do more. “What we’re here to do is to offer campaigning support and expertise.”

The Equality Act states that organisations have a duty to make reasonable adjustments if somebody is at a substantial disadvantage because they are disabled.

While social landlords may be more familiar with reasonable adjustments taking the form of ramps or alternative ways of communicating, requests such as advance notice of visits, clear communication and being kept informed of progress also help keep disabled tenants engaged, happy and safe in their homes.

Damien, who has ADHD, mental health problems and a mobility impairment, says that when he was shown around his London housing association property, the water supply was switched off, masking problems that still plague him. The water pressure is so low that only one tap really works and the shower does not.

While contractors appear to agree with him that repairs are needed, his social landlord contradicts this. Damien reports a litany of excuses and no progress in getting the help he needs.

The problems with his housing association have significantly impacted his mental health and he regrets telling them that he is autistic.

“I approached them with everything on my sleeve. It’s my fault… I just had this assumption that housing associations are fit for people like me,” he explains.

“That was my initial perception, which couldn’t have been more wrong.”

Damien told his landlord about being autistic in the hope that it would improve the way they communicated – “I need clarity” – but he feels ignored and stigmatised and cannot get the plan of action he needs.

Like Ali, Damien fled violence in his previous home. Despite this, he says: “I would rather be under the threat of violence than be in the situation that I’m in now. I’ve never felt this low in my life.”

“They’re stigmatising their own tenants. You very quickly become the problem to be managed”

Damien’s GP intervened to warn his housing association that he was suicidal, but Damien says this made no difference and that the landlord sent him a threatening letter about rent arrears within days.

While Damien wants his landlord to “just be more forthcoming and more transparent”, other disabled tenants require different accommodations. Reasonable adjustments must suit the individual rather than being imposed based on what somebody assumes would help.

Carl had a ‘single point of contact’ (SPOC) enforced on him. This means when he calls his housing association, he can only speak to one designated person.

While this might look like a way to streamline communication and make sure a staff member understands a tenant’s situation holistically, in reality, Carl’s SPOC had been absent for three weeks at the time of our interview and nobody else in the organisation will communicate with him.

Each disabled tenant Inside Housing speaks to describes an atmosphere where landlords assume the worst of tenants. Carl has been accused of talking too fast, while many neurodiverse people are told that they are being inappropriate or aggressive because of the ways they communicate and relate to the world.

“They’re stigmatising their own tenants,” Carl states. “You very quickly become the problem to be managed.”

An inclusive approach to reasonable adjustments helps to protect the dignity of a disabled tenant. If a contractor or housing officer turns up at Carl’s home unannounced, he is faced with either having to divulge his psychiatric diagnosis to a stranger or just refuse the visit without disclosing his private health information, which risks him being classed as uncooperative or anti-social. A simple note on his file that makes his needs clear could prevent this problem.

Ali explains that his housing association does not understand how difficult it is as a neurodiverse person to persist in seeking the adaptations he and his son need. He says that he was recently accused of “fighting” on the phone to his housing association. He says: “I have a persona that I put on when I’m dealing with people who are going to trigger me because [they] don’t believe I’m disabled. I don’t feel supported here. I don’t feel respected. I feel continuously patronised.”

Why a charter?

The Social Landlord Disability Charter Scheme is, Ms Muna says, a living document that can be adapted as time goes on. But one of its key roles is to clearly lay out the problems that disabled tenants face and present potential solutions.

Its focus on neurodiversity, mental health and other hidden disabilities is not accidental. As Ms Muna explains: “It’s not that all of the physical adjustments are being made, they’re not! But there’s more recognition that they need to be made.”

“They know what the solutions are that they need; the housing associations just need to make that connection”

Damien is keen on more support for disabled and neurodiverse tenants because “I don’t think many people like me have the fortitude, or the support, or the voice to do anything about it. So they get away with it more times than not”.

Ms Muna has faith in disabled social housing tenants leading the call for change.

“They know what the solutions are that they need; the housing associations just need to make that connection,” she states.

In July, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities promised to raise the minimum accessibility standard of all new homes, and require level access to entrance-level rooms and easier adaptations. Given that in England only 7% of homes offer minimal accessibility features, this improvement is sorely needed. In Scotland, only 0.7% of council homes and 1.5% of housing associations homes are wheelchair-accessible.

However, as Carl, Ali and Damien’s experiences show, physical access is only part of the picture.

SHAC and DVG have been in conversations with many housing associations about piloting the charter. This includes South Yorkshire Housing Association, which says: “We are absolutely committed to doing more for our customers with disabilities, and believe that the charter provides some excellent guidance and structure for making important changes.”

The landlord adds that it is scoping out the charter, and then its Diversity and Belonging Steering Panel will make a recommendation on whether to sign up.

Meanwhile, Ali has his own priority for campaigning, which goes back to a housing basic: repairs. He states: “The house should already be up to specification before a person moves in because, if not, you’re endangering their lives. You are taking away their dignity.”

*Names have been changed

Sign up for the IH long read bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters