You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Cuckooing: a prisoner in your own home

Research by Inside Housing shows a major rise in recorded cases of cuckooing. How can social landlords support victims of this complex and underreported crime? Katharine Swindells reports. Illustration by Doug John Miller

John* was 68 years old, and had lived in his housing association flat for more than 40 years. For 20 of those he was alone, after his mother – for whom he had been a home carer – died.

Sara*, 30 years John’s junior, was a drug addict. Her husband was in prison, and Sara was in deep debt with drug dealers and loan sharks, who had begun to threaten and physically hurt her. Within days of approaching John in town, she had moved in as his girlfriend. John would lend Sara money for food and train tickets, and to pay off the loan sharks, and she spent much of this on more drugs.

“I don’t know if I loved her, I think perhaps in some ways I did,” John tells Inside Housing. “It was the first time for years I’d been involved with a woman.”

When Sara’s husband Mark* got out of prison, he moved into John’s flat, too. The couple would have loud arguments in the night. Before, John said he had a friendly relationship with the rest of the block, but after Sara and Mark moved in, John said his neighbours would not smile at or speak to him.

Sara would tell elaborate lies to get more money from him, such as saying that her children had been in a car accident and she needed money for the funeral, and John got into increasing debt to give it to her – taking out an overdraft, and not paying his phone, water or energy bills. In the 14 months of their relationship, he calculates that he gave her almost £13,500.

Exploited

The final straw came more than a year after Sara moved in. John’s possessions started to go missing: his radio, his electric toothbrush and even his socks. He told Sara and Mark to leave for good, and Mark punched him in the face. The argument triggered a barrage of noise complaints, which alerted John’s housing association.

The landlord already knew of Sara, as an evicted tenant and from interactions with the police and social services. It immediately moved John out, and he spent a month in temporary sheltered living before moving into a permanent sheltered living flat.

John has worked to pay off his debts, rebuild his life, and come to terms with what happened to him. “I was cuckooed, but I didn’t realise it,” he says. “I was trying to help them, but I was being exploited.”

What happened to John is happening to hundreds, if not thousands, of people across the country every month. Social housing is often the first line of defence in this complex and underreported crime, but how can landlords spot it, and help the victims?

Cuckooing is a fairly new term, used by the police to describe when a person’s home is taken over and used for criminal activity – like how a cuckoo bird takes over another bird’s nest. It is most commonly associated with county lines drug trafficking, but can be associated with other crimes.

Police services do not measure what proportion of cuckooing takes place in social housing, but experts believe it to be the overwhelming majority, in part due to the security of the tenancy.

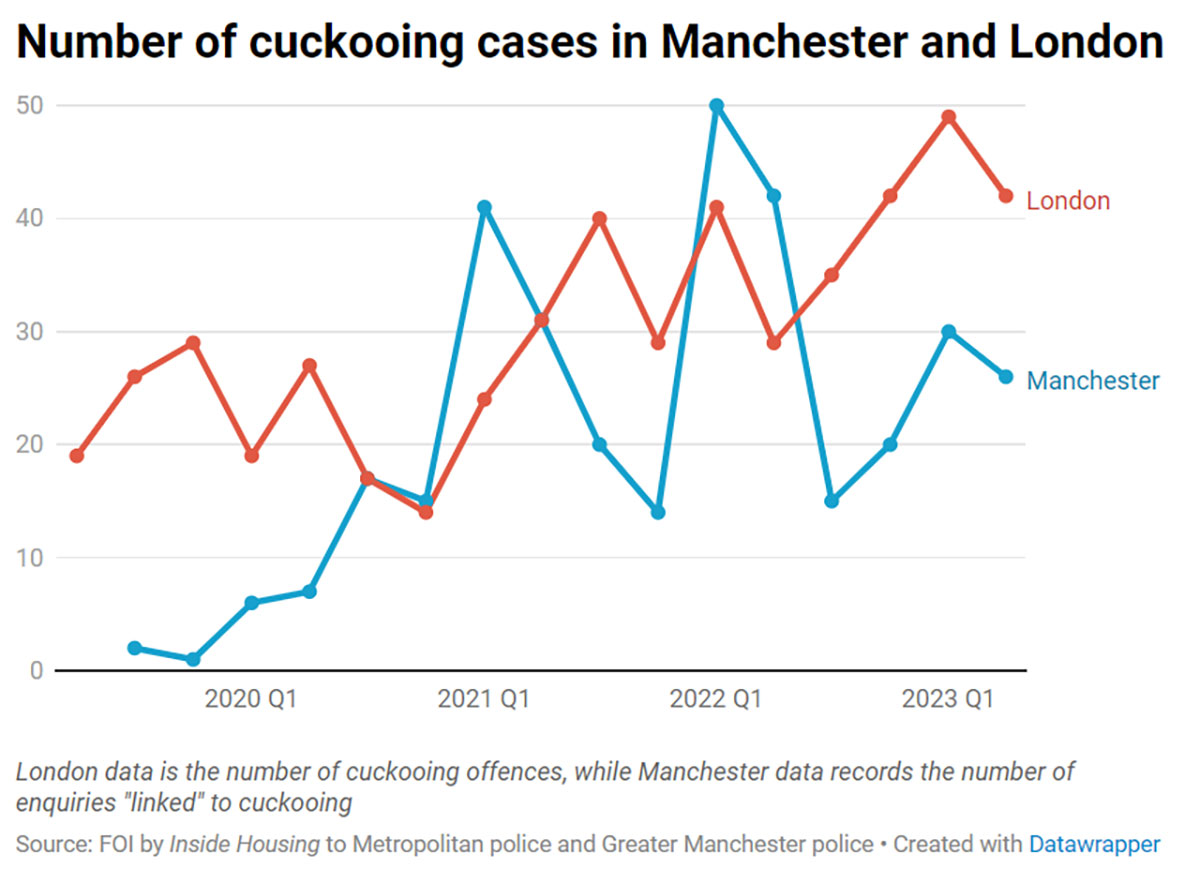

Data obtained by Inside Housing shows that many of the major police forces in England have seen a marked rise in cuckooing cases in recent years (see chart). Freedom of Information requests reveal that of the seven police forces in the country that collect the data, four have seen a significant increase in cuckooing.

London’s Metropolitan Police recorded 91 cuckooing offences in the first half of 2023, 30% higher than the same period in 2022, and more than double the number seen in the first half of 2020.

And these figures are likely to be an underestimate of the actual scale of cuckooing, as they only measure cases of cuckooing recorded by the police. The vast majority of police forces in the UK do not even collect the data, and those that do use varying methods of collection.

Data from London Labour, which used information from councils rather than the police, found that 71 vulnerable adults had to be relocated due to cuckooing at their address in 2022 in the capital – twice as many as the year before. Councils dealt with 300 cases of cuckooing in the capital last year, up 30% year on year.

Even this is still likely capturing only a fraction of cases. Louise Gleich, senior researcher for the Joint Modern Slavery Policy Unit at Justice and Care and the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ), says that many cases fly under the radar because cuckooing is not a crime in itself. If a crime is not being explicitly committed at the property, but the tenant is still being exploited for their home, the police might never flag it.

It then falls, Ms Gleich says, to social landlords to identify cases and intervene. And there is a lot they can do: from supporting victims in having the confidence to turn away cuckoos, to forcibly removing the cuckoos themselves, or obtaining injunctions, to even rehousing the victim if that is what is ultimately required.

“I don’t know if I loved her, I think perhaps in some ways I did. It was the first time for years I’d been involved with a woman”

“Housing associations… are at the frontline in terms of identifying where there’s a problem,” she says.

Across housing providers and charities, many are noticing this rise on the ground. The lack of data collection and the nebulous definition of cuckooing make it hard to track for certain, or pinpoint what may be the reason behind this rise.

“Becoming more aware of it can give the feeling of an increase,” says Sean Jackson, who has worked with a number of cuckooing victims in his role as support services manager at 5,000-home Greatwell Homes. “You intervene sooner, you’re getting out there to check on things a lot more, and therefore it can feel like there’s a lot happening,” he says.

There is also likely rising awareness among tenants, as they are the ones who usually would alert the housing association.

But Katherine Goodwin, Greatwell Homes’ housing and income services manager, thinks the crime is also occurring more frequently, driven by the cost of living crisis and the rise in homelessness. “Those people need shelter and they might find someone or somewhere to make their home,” she says.

In numbers

91

Cuckooing offences recorded by London’s Metropolitan Police in the first half of 2023

65%

Rise in the number of cuckooing cases recorded by Leicestershire Police in three years

Carl Morton also sees the impact of the cost of living crisis in his role as a service manager at St Giles, a charity that supports young people at risk of criminal exploitation. He says rising poverty is undoubtedly making it easier for gangs to recruit young people into criminal activity and becoming cuckoos.

“If you have a young person, the oldest of three kids, whose mum is working two jobs to put food on the table, and his mum can’t spare £2, and then someone comes along and says, ‘I’ll give you 10 times that much’, it’s one of the main ways young people can be groomed by gangs.”

Dettie Wallington, founder of Loughborough-based homelessness charity Exaireo, says that she sees a case of someone made homeless because of cuckooing “at least twice a month” and that she believes the social isolation caused by the pandemic, and then the cost of living crisis, is a key cause.

Indeed, Inside Housing’s FOI request found that Leicestershire Police recorded 43 cases between January and June 2023, a 22% rise on the same period last year, and three times as many as seen in the first half of 2019.

Ms Wallington also thinks underfunding public services is a factor, creating environments where it is easier for cuckooing to happen, and harder to get it addressed. “I just don’t think there are enough police officers or resources for them to be dealt with,” she says.

Targeted crime

Cuckooing tends to be a targeted crime, with victims often approached because they have a learning disability, or because they are older.

“The people who tend to get cuckooed tend to be vulnerable in other ways,” says Ms Wallington. “Previous experience of trauma and domestic violence can make people vulnerable to cuckooing, as can previous experience of homelessness. And, of course, people who are themselves drug users are especially vulnerable, because the dealer plays on that.”

This vulnerability means that the victim may well be resistant to support, if they believe the person cuckooing is their friend.

“If you have a young person, the oldest of three kids, whose mum is working two jobs to put food on the table, and his mum can’t spare £2, and then someone comes along and says, ‘I’ll give you 10 times that much’, it’s one of the main ways young people can be groomed by gangs”

“Often the cuckoo is replacing loneliness, so often you’ll find the customer doesn’t necessarily want them to leave,” says Ms Goodwin. “They may be providing them with drugs, or sexual favours, or even just companionship and filling that gap for them. So to take that away from them can be quite scary, if they don’t see they’ve been taken advantage of, and don’t see the criminal activity behind it.”

Cuckooing also often brings with it a complex victim/perpetrator dynamic. By its nature it brings with it anti-social behaviour and criminal activity, which impact the whole surrounding community.

“Often the first sign that cuckooing is occurring is anti-social behaviour, so the neighbours are usually the first ones that notice,” says Ms Gleich from the CSJ. “So if the neighbour reports it, and the housing association doesn’t ask any bigger questions, then we end up just criminalising the victim and not helping them.”

The victim may well be implicated or even directly involved in the crime or anti-social behaviour (ASB), so it takes thoughtful treatment by the social landlord and police to make sure they get the support they need. Mr Jackson says that this can be “really tricky, because one day one person could be causing a lot of problems in their community, and then the next day, they’re the one experiencing it”. This means staff need to be trained in spotting the signs of cuckooing, and need to have an open-minded approach to ASB that supports those affected and looks into the reasons behind it.

Greatwell Homes’ next step, Ms Goodwin says, is to use marketing materials to improve awareness among tenants of what cuckooing is, and how to spot potential signs in themselves and their neighbours. It wants to make it clear to tenants that the housing association is watching out for its tenants, and help them understand that if they come forward as a victim, they will be believed and supported.

The personal and targeted nature of cuckooing means that if a social landlord can create a culture where cuckooing is quickly identified and addressed, cuckoos will be aware, and are less likely to try. But Ms Goodwin says she knows cuckooing “won’t magically go away”.

“You’ve got to build up strong, trusting relationships with the customers, of you and your partners,” she says.

Everyone Inside Housing interviewed agrees that these partnerships are one of the most crucial parts of an effective strategy to tackle cuckooing – with housing associations, the police, the council, social services, and mental health and addiction support services all working in tandem.

“There is so much knowledge held by housing associations,” Ms Gleich says. “When they are aware and sharing data with other services and networks, they can do so much.”

*Names have been changed and location excluded for the subject’s safety

Sign up for the IH long read bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters