Watch a new film about Ronan Point

Film-maker Ricky Chambers, whose grandparents and mother lived in Ronan Point, has made a film telling people’s stories of the ill-fated block. Watch the film below and read Mr Chambers’ comments on why he made it

Throughout this week we are publishing a number of articles on building safety to mark the 50thanniversary of the Ronan Point disaster

And then we heard shouts and cries is an experimental documentary made in response to a significant historical event of our recent past.

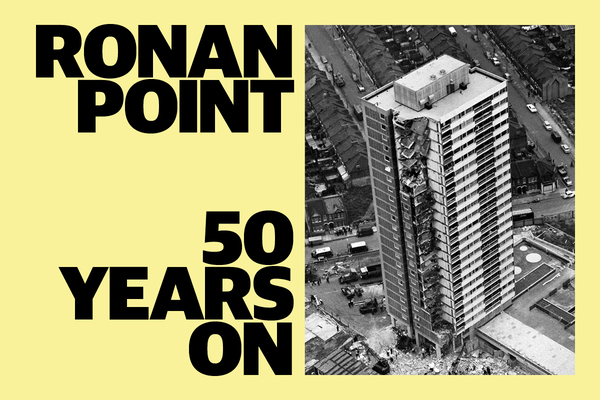

Its principle character is a 22-storey east London tower block, which on 16 May 1968 partially collapsed due to a gas explosion, leaving four people dead.

50 years on, Ronan Point is now absent from the skyline, palpable only through the recollections of those who once lived there.

Over the past year, I have recorded conversations with these people and it is their myriad accounts that form the narration of the resultant film.

For its residents, Ronan Point wasn’t merely a headline, it was a home. People loved, dreamed and died here, children grew up here.

Indeed, many former residents I spoke with said of their fondness for the place and some even lamented its dismantlement altogether.

Of those interviewed, some had been present upon its genesis, others upon its demise: residents, activists, builders and site-engineers, members of the emergency services and a schoolboy, to name just a few.

It was during the process of these conversations that I became interested in the discrepancies between their manifold accounts, and felt it was an aspect that should be foregrounded stylistically within the narrative.

The resulting narration is a heterogeneous re-telling of memory, replete with inaccuracy, myth, confabulation and incongruity as well as factual truths, of course.

Watch the film here:

Watch a new film about Ronan Point

Ronan Point has gone, and so was unable to be rendered visually. As such, the film is a tapestry of traces; of memory, grainy archive and the locale as it is today.

Together with Bob Rush, who was a thirteen year-old schoolboy at the time, I re-visited the site of Ronan Point on Butchers Road, a deprived enclave of Canning Town now occupied by low-rise housing.

His story, was one of an outsider looking in, as though his hands were pressed against the glass window of an aquarium.

"Ronan Point wasn’t merely a headline, it was a home"

He, along with some friends, had wandered through unfamiliar streets to see the ruinous aftermath of the gas-explosion that he’d heard about on the early morning radio announcements.

On arrival, he was confronted with a surprisingly placid scene, statuesque onlookers in quiet awe, punctured by the occasional sound from the patter of loose rubble and a dogs disembodied bark sounding in the distance.

Peering through a temporary cordon, his innocent eyes were witness to the banal fallout of the morning’s horror; a carpet draped over one of the ruptured floors, broken furniture, stray clothing and mounds of detritus still awaiting removal.

With 50 years having elapsed since the initial collapse, and 32 since Ronan Points meticulous deconstruction, recollections such as Bob’s are not as vivid as they might once have been, they may even have transformed, acquired and lost details, or been forgotten completely.

The accounts of these subjects are greatly significant, as a historical portrait but also to generate a wider dialogue in regards to housing, and its use (or misuse).

“It’s my firm and modest hope that an awareness of the Ronan Point tragedy can reaffirm the importance of housing as a basic human right”

The post-war housing boom that led to Ronan Point, might have been weaponized by governments seeking election but they were at least a sincere attempt to improve living conditions and provide social housing.

The position of recent governments however, has been purely rhetorical- when pressured, they are happy to symbolically oppose the flawed practices of this system, though this does little to inhibit them from cynically configuring the very policies required to maintain such unsustainable practices.

A paradigm shift is needed to rectify the housing problem, yet even realistic requests such as the reinstatement of rent controls, long-term tenancies and the provision of truly affordable housing outside the market domain, seem wholly unrealistic in the context of todays “there is no alternative” status-quo.

In response to this climate, it’s my firm and modest hope that an awareness of the Ronan Point tragedy can reaffirm the importance of housing as a basic human right.

Ricky Chambers, film-maker

Ronan Point: 50 years on

We have published a series of articles to mark the 50th anniversary of Ronan Point:

Are tenants being listened to on building safety? Tower block safety campaigner Frances Clarke questions whether Dame Judith Hackitt is really listening to tenants

The tower blocks that time forgot Fifty years ago councils were told to assess high-rise buildings that were similar to Ronan Point and strengthen them where necessary. So why are problems with some of the blocks still emerging?

One man’s 50-year battle to improve tower block safety Meet architect Sam Webb, who has been campaigning on safety in tower blocks since the disaster at Ronan Point

The worrying legacy of a disaster Jules Birch reflects on what we can learn from the Ronan Point disaster

Watch a new film about Ronan Point Filmmaker Ricky Chambers, whose grandparents and mother lived in Ronan Point, has made a film telling people’s stories of the ill-fated block. Watch the film and read Mr Chambers’ comments on why he made it

The dangers of large panel system construction Building safety expert Sam Webb explains why the system of construction used at Ronan Point was flawed, and how it was used in other buildings still occupied today