You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Jules Birch is an award-winning blogger who writes exclusive articles for Inside Housing

The UK Housing Review raises important questions on where housing is heading

The UK Housing Review shows that spending on the Affordable Homes Programme is peaking this year, and highlights the questions for the direction of all parts of the housing sector, whether that is social housing, private rent or homeownership. Jules Birch sifts through the report for the most interesting lessons

So where next? The publication of the UK Housing Review today is a chance to take stock and ask where the housing system may be heading.

The sense is one of considerable flux. For homeownership, as the housing market downturn continues. For private renting, as the momentum behind increased regulation grows. And for social housing, as landlords face competing demands for scarce resources.

The paralysis of policy signalled by a Budget that mostly ignored housing could be just a temporary lull ahead of a UK general election.

As ever, the review puts all that into context. For starters, John Perry’s chapter on housing expenditure shows where total government support (in grants, loans and guarantees) for housing is going. The balance between the private market (59%) and affordable housing (41%) may not be quite as skewed as it was in the heyday of Help to Buy, but it is still tilted in one direction.

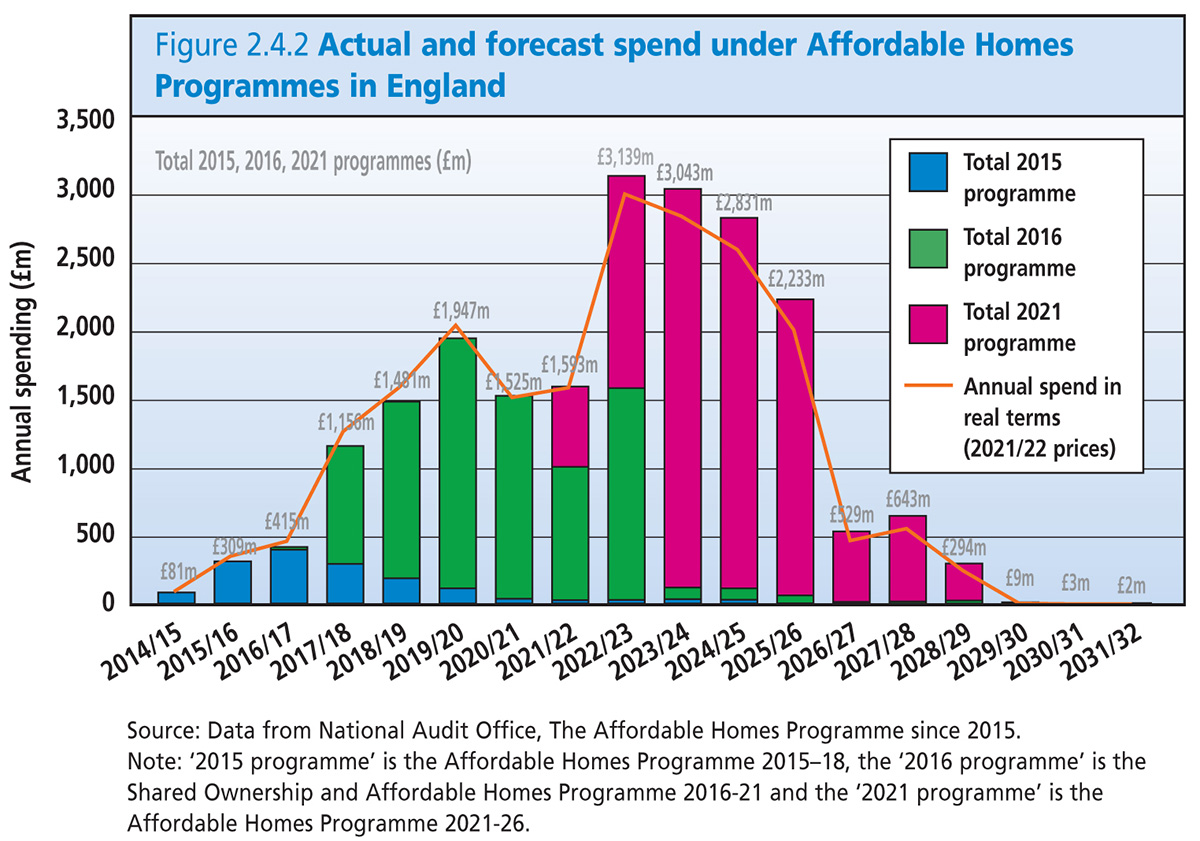

The good news is that public spending on affordable homes has risen in real terms since the dark days of the coalition government. Investment under three Affordable Homes Programmes is set to peak this year, but the looming cliff-edge is an indication of the big decisions that lie ahead:

Current spending plans (as in the Budget) rely on eye-watering (and unrealistic) austerity after the next election so that they comply with the chancellor’s fiscal rules. Key decisions lie ahead in the spending review after the next election regardless of who wins.

What is getting built is also skewed. There were 59,175 affordable housing completions in England in 2021-22 – the highest for 11 years. However, more than 20,000 of those were for affordable homeownership and 28,000 for affordable rent, leaving just 7,528 for social rent (plus another 3,080 for similar London Affordable Rent).

Contrast this with Scotland, which managed 9,757 affordable completions in 2021-22, including almost as many social rent homes (7,306) despite having a population about a tenth of England’s.

“Modelling by Heriot-Watt University predicts that temporary accommodation placements in England are set to double over the next 20 years”

With a record like that, it’s no wonder that the chapter on help with housing costs by Sam Lister and Mark Stephens shows a system under pressure.

That starts with the growing inadequacy of basic social security benefits that were never designed to cover housing costs.

Housing benefit was meant to take the strain of the higher rents generated by the changes introduced after 1988, but that was before the cuts, restrictions and freezes of the 2010s.

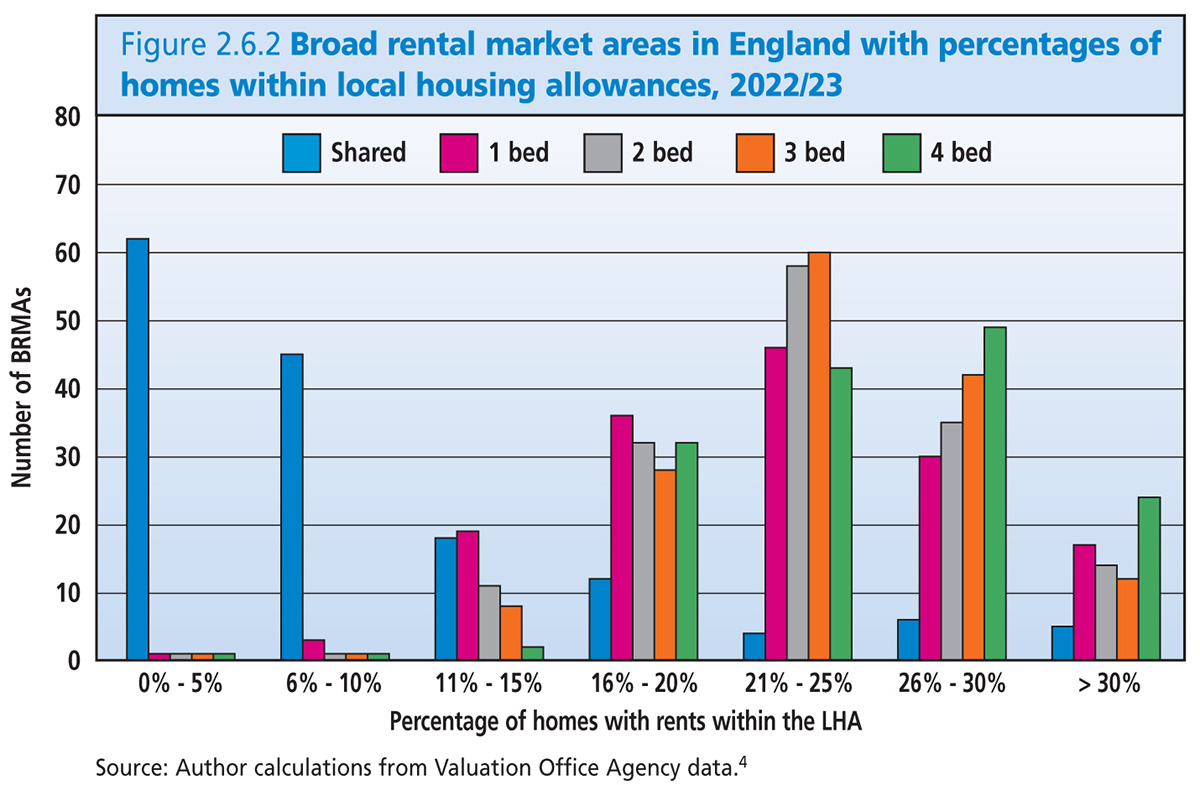

Local Housing Allowance (LHA) was at least restored to the 30th percentile of local rents in 2020, but was promptly frozen again. This graph below shows how few local areas have private rents that are affordable within LHA rates this year:

That is just for this year. With the Budget confirming that LHA will be frozen again in 2023-24, at a time when rents are rising rapidly, those columns will shrink even further.

The results of that combination of unaffordable housing and inadequate benefits are highlighted in Lynne McMordie’s chapter on homelessness.

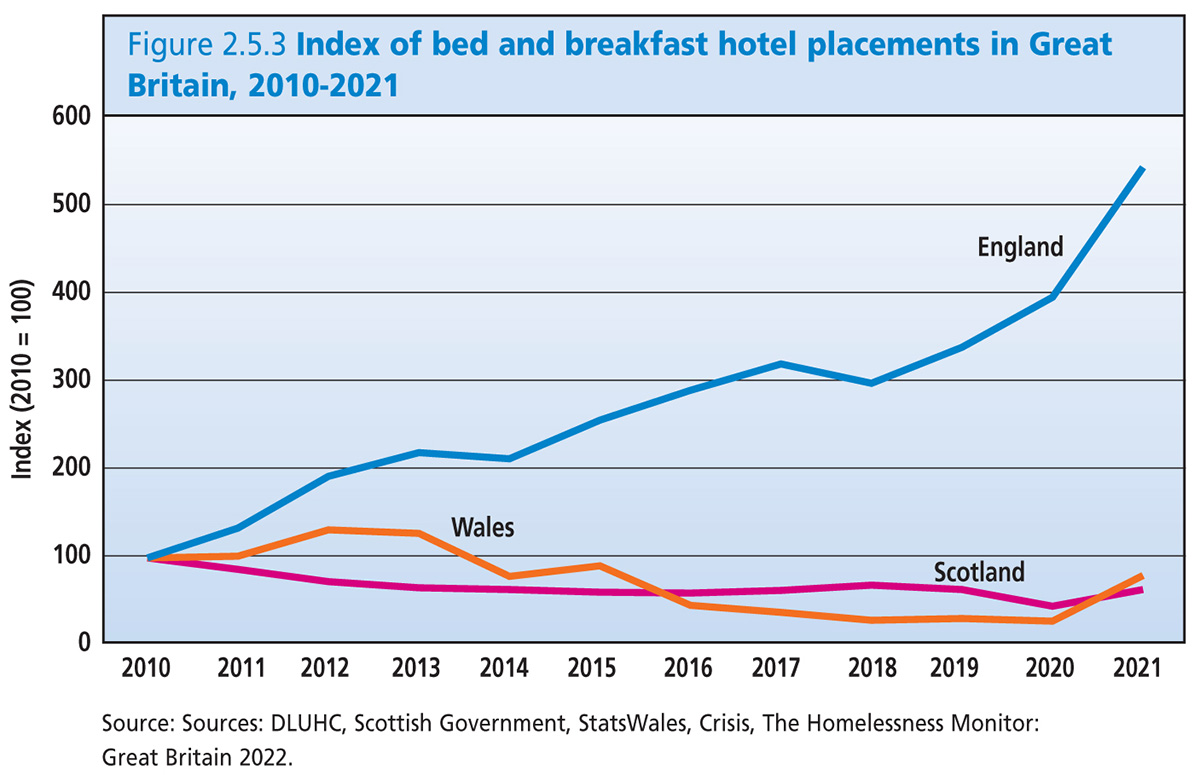

While use of temporary accommodation for homeless families has risen across Britain, the scale of the problem in England is shown in the huge increase in the use of bed and breakfast hotels in the past decade:

And those problems are only set to get worse. Modelling by Heriot-Watt University predicts that temporary accommodation placements in England are set to double over the next 20 years.

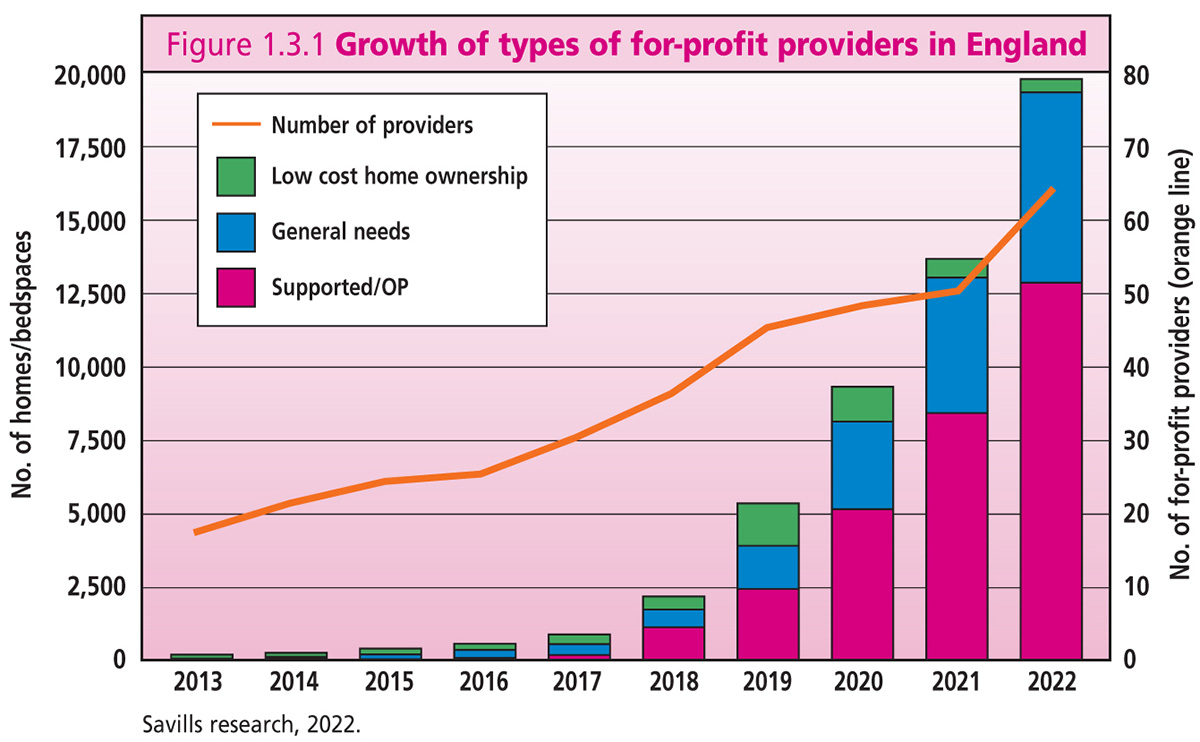

Is there any good news on the horizon? One bright spot might be the new sources of financing for affordable homes highlighted in Steve Partridge’s chapter on the emergence of equity investment and the rise of for-profit providers.

He argues: “Given the prevailing economic and inflationary context, and pressures on the existing asset base through building safety and preparing for net zero, it is possible that equity investment will, over time, become the dominant source of capital for new affordable housing investment.”

This graph below shows the rapid growth in the number of homes and bedspaces owned by different types of for-profit providers over the past 10 years in England:

Research by Savills suggests that could just be the start. By 2027, there could be around 90 for-profit providers with 141,000 homes between them and £27bn invested.

Mr Partridge concludes there is an emerging market for partnerships with investors and that this represents an opportunity rather than a threat for existing social landlords. “Far from seeing the growth of equity investment as somehow a separate sector, it is far more likely that such investors and the established sector will become important partners in addressing the supply and delivery of affordable housing, for decades to come,” he says.

The chapter does not really consider how much it matters where the financing for affordable housing comes from, but it left me wondering.

Patient investment in affordable homes by pension funds looking to tick their environmental, social and governance (ESG) boxes seems to make sense in both directions.

“Even if the new investors stick to providing new affordable homes, rather than exploiting the value tied up in existing ones, how affordable will they really be?”

With not-for-profit landlords facing up to the need to invest in their existing stock and public investment likely to be limited whoever wins the next election, new sources of finance are desperately needed.

However, if we needed any convincing that this is also about hard-nosed investment, the involvement of Wall Street giants like Blackstone and BlackRock is surely one indication – and a quick look at tensions in the low-income housing sector in the United States should sound a loud note of caution.

Even if the new investors stick to providing new affordable homes, rather than exploiting the value tied up in existing ones, how affordable will they really be? Won’t all the incentives be for developments that deliver the highest returns rather than those that deliver the most affordable rents? Which takes us right back to where I began this column.

As usual, this year’s review features analysis that goes across tenures and across the different countries of the UK as well as the most comprehensive set of housing statistics out there. This edition also includes contemporary issues chapters by Mark Stephens on the housing market and levelling up, Ken Gibb on changes in the private rented sector, and me on the regulation of social housing.

The 2023 UK Housing Review has been launched and published today. To find out more and to see previous editions, click here.

Jules Birch, columnist, Inside Housing

Sign up for the IH long read bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters