You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

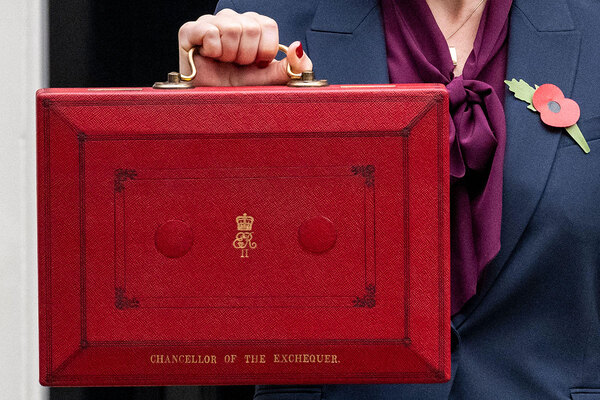

The Autumn Budget and social housing finance: is the impending Comprehensive Spending Review a watershed moment?

Brendan Nevin, director of North Housing Consulting, analyses the finances promised in the Autumn Budget and what they mean for the sector

The 2024 Budget has set the scene for housing and public services for the rest of the parliament. The Budget has been agreed for 2025-26 with a spending envelope up to 2029-30 that will be distributed across government in spring next year in a Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR).

The Budget announcements saw the government achieve the difficult task of stabilising government finances while buying time to assess how to reform public services and promote a growth agenda. This is supported by a 2% per annum average increase in revenue funding, the largest investment in services since the 2000 Spending Review.

Additionally, because of a shift in the definitions of public sector debt, a further £100bn of capital investment has been allocated in total over the five-year planning period.

The path to success, though, is fraught with difficulties.

First, the financial support for services is heavily front-loaded into the first two years, with increases of 4.8% and 3.2%. This is entirely understandable because of the need to prevent collapse in basic services before reform and efficiency programmes can be implemented.

However, the settlement for the final years of the parliament flatlines at 1.3% per annum. This is very low by historical standards and will put further pressures on unprotected services such as housing and local government.

In other words, without additional economic growth above the current baseline, expect more pressure to reshape service offers across the public sector (and maybe some services currently defined as private sector such as water, rail and social housing).

“Without additional economic growth to that which has already been forecast, expect more pressure to reshape service offers and change organisational form across the public sector”

Second, the £100bn of additional capital investment has not been considered by the Office for Budget Responsibility to have a short-term impact on growth. This, perhaps, is not such a surprise when we consider that the increase partially offsets decreases that were programmed in by the previous government.

In 2023-24, public sector net investment was 2.6% of GDP, while in 2029-30 it is projected to be 2.4%. This is not an investment bonanza that turbo-charges growth. We should, therefore, assume a greater focus on public service reform rather than increased funding as this parliament progresses, as increases in the tax take will be limited.

Third, we need to consider new and existing spending priorities generating additional demands for extra cash. The government currently has an unfunded commitment to increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP, the costs of climate change are rising, the population is ageing, and health pressures will continue to rise with it.

Health now accounts for 42% of all service spending up from 32% in 2010. Over the past 40 years, the nation has shifted resources from defence and interest payments on debt to pay for increases health and social care. All four of those issues will in future require more funding from a tax base that has been depleted by low growth since 2008, which in the last parliament was negative when measured on a per capita basis.

This is the context for the government when assessing how to meets its new priorities of economic growth, green energy infrastructure, a sovereign wealth fund, new roads and railways, and 1.5 million new homes with a step change in social housing outputs.

Looking at the housing objectives, the Autumn Budget allocated an additional £500m of grant to the 2025-26 Affordable Homes Programme, an investment that should produce an additional 5,000 social housing units.

This is investment that will kick-start a new programme which will be released by the CSR next year. It provides an increase in the 2021-26 Affordable Homes Programme, which had a flat profile of about £2.6bn per annum, so in the final year of the programme, the £500m uplift represents an increase of 19.2% in grant funding.

To sustain this uplift over the remainder of the parliament would mean that new baseline of £3.1bn would need to be rolled forward, but this is unlikely to generate a step change in delivery to 2029-30.

“The elephant in the room with the housing debate is the damage that has been done to balance sheets by several successive reductions in income imposed on social landlords since 2012”

Housing could receive more support than this from the £87bn of unallocated capital, a doubling of the 2021-26 programme would require an extra £10.4bn spread over four years, but the key question is how this will affect outputs given recent increases in inflation and a higher subsidy need for social housing.

The chances of achieving this scale of increase in resources would seem slim given the demands to increase economic growth, repair hospitals and schools, build new prisons, and reinforce the military. A lot rests on the planning system and the Homes England investment model delivering new social housing supply if the government is to meet its objectives.

The elephant in the room with the housing debate is the damage that has been done to balance sheets by several successive reductions in income imposed on social landlords since 2012. Can the sector afford to improve its stock quality, meet climate change targets and contribute to new build in the future?

The debate over revenue funding is likely to come into sharp focus over the next few years and there is o resource set aside to resolve the issue. This is a government that supports social housing but there may be stronger arguments for funding elsewhere.

There are better arguments to secure resources if social housing agencies were to sharpen their offer around the prevention agenda and embed it in the government’s key mission statements. This would entail a greater integration with health, education and employment services and would lead to new forms of partnerships and a pooling of resources with government agencies.

A reformed service offer, changes in organisational arrangements and uplifting the quality of existing accommodation could be the medium-term primary focus, and growth could be an important secondary consideration until a new model shows improved people and place-based delivery and the economy finds a new growth trajectory.

Brendan Nevin, director, North Housing Consulting

Sign up for our development and finance newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters