How the housing sector is generating new energy

Innovation is required to make new technologies work in the face of climate change, explain David Kemp of Procure Plus and Professor Will Swan of the University of Salford

Picture: Getty

Article written by:

Registered providers (RPs) of social housing are increasingly finding themselves caught in the middle of a debate related to climate change.

As we all know, this topic goes beyond the moral issue of this current generation leaving a planet that is habitable for the next one. Climate change as a topic is interconnected with myriad issues, with some seemingly more pertinent to social housing providers than others.

Reducing operational budgets, fuel poverty, health and well-being, urban air quality, constraints on the electricity network, and increasing levels of intermittent renewable energy generation all in some way link back to the climate change agenda – which RPs have a role in tackling.

With the UK government’s 2050 net zero-carbon target now enshrined in law and with various local authorities and combined authorities, including the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, setting their own zero-carbon deadlines and declaring “climate emergencies”, there is a greater expectation from public sector bodies that RPs will step up and lead by example to achieve these goals.

So what are the actual implications for RPs?

In a nutshell, there will be a requirement for them to manage their stock in such a way that dwellings have lower maintenance costs or are able to generate additional revenue to offset costs, emit less carbon, have lower energy costs for residents, reduce emissions of gases and particulates that contribute to poor air quality, reduce stress on the electrical network, and support the transition to a low-carbon, renewable heavy energy system. That’s no small feat.

Some technologies that can address elements of this wider challenge are known now: air and ground source heat pumps, solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, energy storage solutions and insulation systems. However, when deployed on their own, they aren’t able to address the issue holistically.

For example, a PV battery system helps deal with fuel poverty and reduces stress on the local network but does little to deal with the technical issues surrounding greater deployment of intermittent renewable energy generation, reducing carbon associated with heating properties (the biggest source of emissions from homes) or reducing an RP’s operational costs.

This is where and why innovation is required from RPs as well as the businesses, supply chain companies and research institutions that will be needed to develop, refine and offer products and services to help RPs achieve these objectives.

There are a number of examples of RPs exploring how their respective organisations can maximise the opportunities presented by the climate change agenda, while also addressing the moral and social imperative argument, in advance of and in preparation for the inevitable reverse incentive regulation ‘stick’ that will follow. Likewise, businesses are working with research establishments and universities to exploit emerging opportunities and gain first mover advantage in these new markets.

What is clear is that RPs need to move away from business as usual. Those that look to innovate now have the opportunity to inform, develop and benefit from a changing landscape, whereas those that follow might not.

Meeting the 2050 target

Sustainability consultant Richard Lupo summarises the results of research undertaken with six landlords and outlines recommendations

The target set out by government to become carbon neutral by 2050 is an ambitious goal. As the social housing sector accounts for about 17% of all homes, it will have a significant role in helping to reduce emissions. Social landlords have a responsibility to ensure that existing homes and new builds planned for the next 30 years are all striving to reach this goal.

Registered providers need to act now with a solid plan. This means that new financial plans will be required to help social landlords fund the work.

The current situation

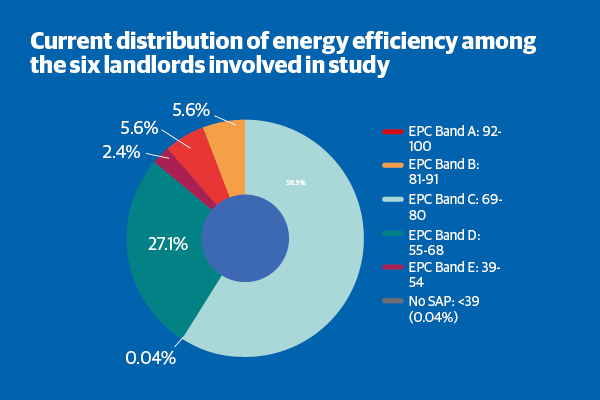

Sustainable Homes Index For Tomorrow (SHIFT) undertakes environmental reporting, benchmarking and accreditation for social landlords and recently surveyed a group of landlords who represent more than 240,000 UK homes. We found that the majority of homes are in the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) Band C category (A is very low energy and G is extremely high energy).

Our previous research in 2012 indicated that a target mid-B average corresponds with the 80% carbon reduction, which was in the Climate Change Act 2008.

This may be revised now that government has committed to 100% reduction. For now, we recognise that 80% is still a good target and the remaining 20% reduction will be from offsets.

All this means that social homes are not on track to reach the mid-B average by 2050 and very few landlords have plans for deep retrofit beyond 2030.

We found minimal action to transition away from gas as a heating source. This is despite government signals to decarbonise heat in domestic properties.

There was some success with Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery (MVHR) systems in new build homes, as the systems functioned well and residents found that their bills were reduced.

Although not officially classified as low-carbon heat for Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) purposes, MVHR certainly is very low carbon. The system recycles internally generated heat and solar energy relying on high levels of insulation in the home, as well as solar energy and human activity in the home. After evaluation, the key message was that these systems need to be designed, installed and commissioned by competent contractors.

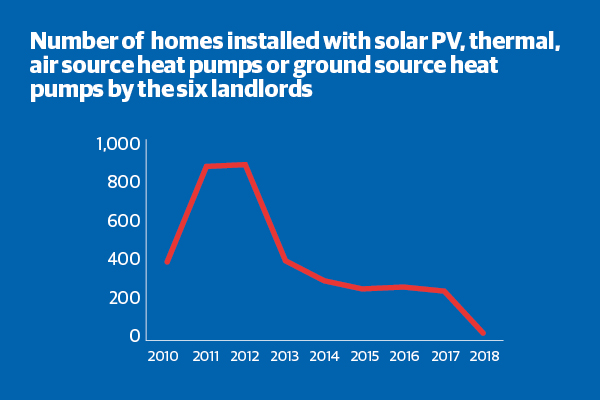

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the research found that investment in renewable electricity has generally declined because of a lack of funding.

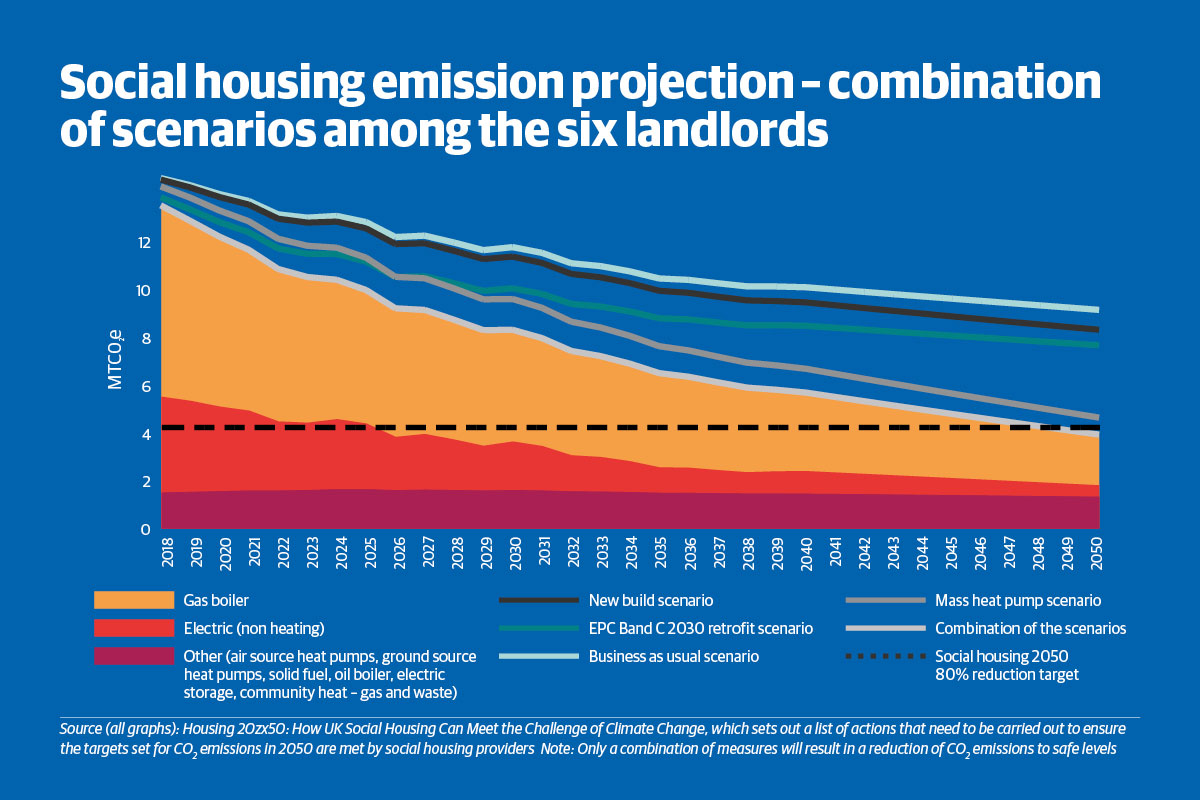

The EPC ‘C’ by 2030 target is on the radar for some landlords because of the government’s fuel poverty strategy. However, as part of the research we evaluated the current changes in home improvements, new builds, projected new build standards and decarbonising the electricity network over the next few decades, and with all this potential activity we concluded that this alone wouldn’t be sufficient to reduce CO2 emissions down to the safe levels.

The good news is that a combination of higher new build standards, renewable installation, deep retrofit and low-carbon heat will achieve 80% CO2 reduction but only provided that landlords start planning for this now.

In pursuit of sustainability

While undertaking the study, we found numerous examples of how pursuing energy efficiency for homes provided financial benefits to the landlord. Examples include:

- Emerging ‘pay-as-you-save’ schemes where the landlord charges the resident an ‘energy plan’ in retrofitted homes – the charge is far less than the residents’ energy savings so both parties are

financially better off. - Offsite manufacture for new build driven by cost savings and improved new build standards.

- Landlords had renewable heat equipment installed for free while the supplier claimed the grant.

- Recent Welsh rent policy has allowed social landlords to increase the amount of rent they can charge in proportion to the energy efficiency of their homes.

- MVHR systems lead to reduced damp and condensation, which result in lower disrepair claims.

- Installation of PV panels for free, then supplying residents with the electricity generated at a low rate.

Other interventions result in surprising cost savings, for example smart thermostats that increase efficiency of the heating system and also predict when a resident is at home so that energy isn’t wasted.

Click on graph for larger image

The next step

The ideal approach is to start work now with an aim to reap the financial rewards. This will be less disruptive than waiting for new regulations to come into force.

For existing homes, landlords should develop a whole-house retrofit plan for each home to be updated to a high level of energy efficiency aiming for an average ‘mid B’ – Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) 86 to be exact. Interventions may not be affordable right now, but it is essential to have a plan to prevent ‘dead end’ technologies being installed. Focus on insulation first.

For funding, experiment with emerging financial sources such as ‘pay-as-you-save’ energy schemes to pay for the upfront cost of upgrades to allow you to pay back over time through the energy savings you make.

Investigate the links between energy-efficient homes and reduced maintenance costs for your own organisation. This will help make the business case for increased energy efficiency.

Educate and upskill relevant staff in energy efficiency, new technologies and your long-term plan. This will mean that only correct interventions are deployed.

If, however, you are considering developing new housing stock, ensure the grade SAP 86 is the minimum build standard – anything lower and you would be building a retrofit project.

Experiment with low-cost builds that will result in energy-efficient homes, including MVHR systems. For example, offsite manufacture results in lower emissions than standard build.

As well as helping to prevent extreme adverse effects of climate change, the opportunities for increased financial income and cost savings are immense.

Ultimately, following a low-carbon agenda can help housing providers deliver on their social purpose by ensuring that residents have resilient, high-quality homes, low energy bills and access to new technologies that facilitate a low-carbon lifestyle.

Richard Lupo, sustainability consultant and managing director, Suss Housing

Article written by:

Energetic homes

Three projects are being trailed to test models that will enable homes to be energy efficient and can be adopted by landlords (picture: Getty)

In association with:

Energy House 2.0

How it will work: Houses and commercial properties of different sizes will be built inside environmental chambers

The difference in how well a ‘green’ product performs in theory and in reality can be considerable.

Usually, real-world testing only takes place once the tech has been installed in buildings, but that is about to change.

Next year, an enormous black box will begin to take shape on the University of Salford’s campus. Inside will be two environmental chambers, each large enough to accommodate a sizeable detached house. When completed, that, along with homes and commercial properties of all shapes and sizes, is exactly what will be built inside it.

This is a project called Energy House 2.0, and its purpose is to produce reliable data on the environmental performance of products and properties of all kinds.

“The social housing sector is looking more at offsite and other modern methods of construction – that is one of the big focuses of our research,” says Professor Will Swan, director of the University of Salford’s Energy House Laboratories.

“We want to build these houses and see how they actually perform, because what we do know is that the way things are designed to perform and the way they are built to perform are two very different things. We are all about measuring things to make sure they do exactly what they say on the tin.”

The £16m project is a big step up from the university’s first Energy House project, now a decade old, in which a Victorian house was built inside an existing environmental chamber.

“The first iteration was about testing [green] products and was very much focused on that particular type of housing,” explains Dr Richard Fitton, technical research lead for the Energy House project.

“The difference with Energy House 2.0 is that we can build anything we want. We want to support the green sector by giving them a place where they can test their products very quickly and under controlled and repeatable conditions. It will be one of the only places in the world you can do that, and we can then start to put that evidence together to help people make informed decisions.”

Social housing developers trial lots of new technology, he says, but if something doesn’t work as well as it should, the lack of real-world testing facilities means it’s usually already been installed.

“We’re here to make sure it works, before you get to that point,” he says.

Together Energy

How it will work: Homes will be installed with solar panels and battery storage, which will store energy and use it when needed

The winding down of feed-in tariffs (FIT) has posed quite a challenge to social housing providers.

Since 2010, these subsidies have been a significant plank of the business case for installing small-scale renewable energy in social housing.

Now that the FIT programme has been wound down – it ended at the end of March 2018 – providers will have to find another way to make renewables’ most obvious benefits – cheaper energy and a lower carbon footprint – financially justifiable.

Could battery technology provide the solution? Landlord Together Housing is conducting a pilot in order to find out.

Battery storage is a game changer. Without it, excess energy generated by solar panels is returned to the network, which is low value for Together Housing and can cause problems balancing the grid. With batteries, however, that energy can be stored and used as necessary – and that opens up new revenue streams that will, the landlord hopes, turn investment in renewables from a cost in to a source of income.

The association is installing battery storage alongside solar photovoltaic installations on 250 of its properties. The project is looking at three potential sources of revenue: selling energy to tenants at below market rates, selling excess energy to other tenants at closer to retail prices, and pooling these installations to work together to help balance the load on the National Grid.

The project will run until March 2021 and will cost just shy of £2m. Patrick Berry, managing director at Together Energy, believes that the business model his team is testing could spark a revolution in the way social landlords approach green energy.

“If this works at scale, it can help this sector in the drive towards renewables,” he says. “If I can make the business case, I want to make this, over the next 10 to 15 years, the norm for as many of our houses as possible.”

However, making the business case, Mr Berry says, will depend on empirical data. “The point of this project is to gather that market data and to do it in an open way, so we can share it with others in the social housing and local authority sectors,” he adds. “There is an opportunity with these technologies for the social housing sector to become market makers. We will distribute what we find, the analysis we do, and how that impacts on the financial model, to all those who are interested.”

Homes as Energy Systems

How it will work: Returns from solar, battery and heat pump technology from homes will be used to create a virtual power plant

Greater Manchester is aiming to become a zero-carbon region by 2038. The residential sector will have to play a large part in achieving that goal through the increased uptake of climate-friendly technologies, as well as through retrofitting properties, to make them more energy efficient.

The only problem is that this costs. Previous efforts to finance domestic energy-efficiency measures have not always been successful.

Now that feed-in tariffs are no longer a source of revenue, the search is on for new business models that can provide financial returns as well as improved sustainability.

One example is now being trailed in Greater Manchester. It is called Homes as Energy Systems (HaES), which is part-funded by what could be some of the last European Regional Development Fund* (ERDF) cash to benefit the UK.

Its lead, David Kemp, believes this project will provide proof of concept for a new business model that ticks all the boxes.

“What doesn’t generate a revenue, and is hard for financial directors to justify, is the stuff that really needs to be done to our properties at scale: improving their thermal efficiency,” says Mr Kemp.

“With insulation, for example, there is no meaningful return to the property owner other than the moral imperative to do so. But we can demonstrate that we can cross-subsidise the improvement work that needs to be done by slapping on some stuff that generates an interesting return.”

The HaES model depends on leveraging returns from residential solar, battery and heat pump technology by aggregating over 700 properties across Greater Manchester, using project partner Upside Energy’s software platform, in to what is called a ‘virtual power plant’.

When functioning as a single unit, these properties can help balance the load on the national and local network either by drawing energy from it when there is a surplus or pushing out energy when there is a shortfall – both services which the National Grid currently pays.

“We want to demonstrate that a dwelling doesn’t have to be a drain on the energy system at the end of a wire,” says Mr Kemp. “It can actively contribute to dynamic grid management.”

And, crucially, the more energy efficient a property is, the greater the revenues generated by the virtual power plant. This increased revenue will, it is hoped, provide the business case for investing in retrofit.

Most of the pilot’s properties are managed by two large social landlords: Northwards Housing and Stockport Homes Group.

The project will also include around 20 privately owned properties that will be retrofitted.

Social enterprise RetrofitWorks is leading on this ERDF-funded element. Sensors in each home will hoover up data, which will be captured and analysed by the University of Salford. The findings will, Mr Kemp hopes, provide the proof that this model works.

*The project received £5.2m of funding from the England European Regional Development Fund as part of the European Structural and Investment Funds Growth Programme 2014-20. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (and in London the intermediate body the Greater London Authority) is the managing authority for the European Regional Development Fund. Established by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund helps local areas stimulate their economic development by investing in projects which will support innovation, businesses, create jobs and local community regenerations. For more information, visit

www.gov.uk/european-growth-funding