Furniture poverty: the impact on tenants’ lives

Furniture poverty has harsh consequences for children and adults. Alison Inman explains what needs to change

In association with:

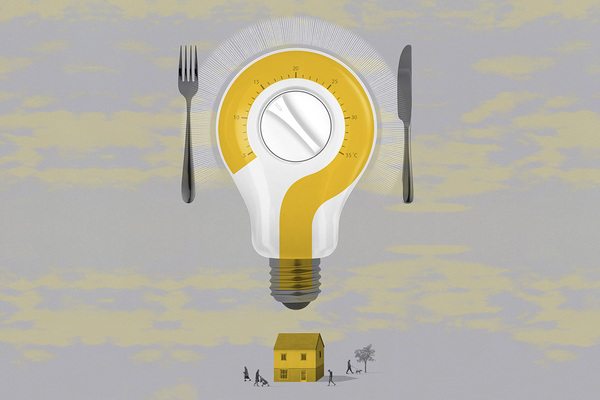

If the social housing sector is ever going to get to grips with furniture poverty, it must first understand how this blight on tenants’ lives fits into the bigger poverty picture. I’m not sure the sector has a handle on poverty full stop. So I think it’s incumbent on all of us to take a step back, look at the broader landscape and ask ourselves some searching questions.

A big one is: why do we spend £140,000-£150,000 building a new social housing property and then put people in it who, in some cases, can’t afford a bed or curtains? We can’t congratulate ourselves for putting a roof over someone’s head if the roof is all there is. If people don’t have furniture and white goods, their lives will be made immeasurably poorer and harder in all sorts of heartbreakingly insidious ways, because the knock-on effects of furniture poverty are enormous.

Last year, I talked to John Roberts, founder of online appliance retailer AO, and a board member of OnSide Youth Zones, who wanted to introduce an affordable rental model for white goods in social housing tenancies. He said he desperately felt the need to do something because some kids living in social housing were coming to the Youth Zones and finding that no one wanted to play with them because they smelled. That’s what happens when you don’t have access to a washing machine or somewhere to dry your clothes.

The impact of furniture poverty on children can be particularly harsh. If a child doesn’t have their own bed, they’ll be tired at school the next day because they won’t be getting a decent night’s sleep, and their grades will suffer. If there’s nowhere to sit, they aren’t going to have their friends round after school. If their family can’t afford blinds or curtains, what will they put up at the windows instead? Whatever it is, it’ll immediately mark the child out as ‘different’.

Furniture poverty has a major impact on adults, too. Not having a cooker means a person will rely on takeaway food, which has implications for their health. If they’re drying their washing on the radiator because they have nowhere else for it to go, and they don’t want to open the windows because they can’t afford to have the heating on, they’ve suddenly got a big problem with damp. Which they wouldn’t have if only they had access to a condenser tumble dryer.

Holistic approach

Only 2% of social housing properties are available to rent furnished, versus 29% in the private rented sector. But, ironically, the homes that housing associations build for open market sale and shared ownership often have white goods installed in them. Think about that. It’s basically saying: “If you’ve already got enough cash to buy your own home, we’ll throw in a washer dryer for you.” Meanwhile, those people who are poor enough to access social housing are given nothing.

In numbers

2%

Percentage of social housing properties that are furnished

29%

Percentage of private rented sector properties that are furnished

Worse than that, in many situations, landlords will take items out of their properties during the void process and junk them. Someone left a piece of furniture in the garden because they couldn’t afford to have it taken away? No problem. We’ll put that on the tip. Has a tumble dryer been left by the previous tenant? Or does that carpet need to come up because it’s failed a risk assessment? Out they go into landfill. And then the next tenant moves in to an empty box.

Perhaps environmental, social and governance reporting will stop that sort of thing. But, still, the worry remains: because of furniture poverty, some people won’t be able to afford to live in lower-rent homes. Or those who end up with high-interest loans to get the bare minimum won’t be able to pay their rent as a result.

So my message is: we need to start looking at the problem of poverty in a holistic way and think about the entire experience of social housing living. Yes, this is a complicated issue, but with a joined-up approach, simple solutions shouldn’t be beyond our reach. Rental models, with payment coming from housing benefit or Universal Credit, can work well. Lease-based models or affordable furniture stores might be a better option for others. And if a tenant leaves a washing machine when they move out, make sure a legal document is available so that the appliance can be gifted to a new tenant.

Part of the answer is good housing management and knowing your community. Housing officers should notice when, say, a property has no curtains or there’s condensation at the windows, and act.

Admittedly, it is not a uniform picture across the sector – and some landlords understand the issue and are trying hard to find ways to fix it. And we don’t need to give everything to everybody, because some people in social housing properties do have access to furniture and white goods. But some people have literally nothing. Which is why it pains me to say that, when it comes to furniture poverty, we currently haven’t got a clue. And we badly need to start getting one.

Alison Inman is a board member at Saffron Housing and Tpas; and co-founder of SHOUT

“Everyone should be able to access the basic items that make a house a home”

James Hudson, assistant director of commercial strategy and growth, Your Homes Newcastle

Imagine choosing between paying bills and buying food or having a fridge, a freezer or a washing machine. For millions of people who are on low incomes and live in unfurnished tenancies in the UK, that’s reality. Yet – it should go without saying – everyone should be able to access the basic items that make a house a home.

Last year, poverty charity Turn2us produced a report that was as powerful as it was alarming. It revealed that 1.9 million people in the UK don’t have a cooker, 2.8 million are living without a freezer, and 900,000 don’t have a fridge. A further 1.9 million people can’t afford a washing machine. The direct consequences of not being able to cook, store food or wash your clothes are fairly obvious. But furniture poverty also has less obvious – but no less pernicious – financial, social and health implications.

Tenants living in unfurnished properties may need to borrow money to buy essential furnishings and so run the risk of racking up debt. They also have the conundrum of establishing bill-paying priorities. If they’re without a washing machine, do they go to the launderette, or not wash their clothes?

Some landlords perceive furniture as another asset to be maintained and managed, so it’s no surprise that only 2% of social housing properties are let as furnished or partly furnished (Understanding Society data, 2018). Some landlords offer grants or purchase furniture on customers’ behalf, but it can open up the age-old complications around fairness, expenditure, asset management and what to do if a customer moves.

But there are solutions to the issue of furniture poverty. NFS champions an end-to-end rental model that gives customers the choice of the furniture they want, accessible through housing benefit or Universal Credit. The flexible furnished tenancy service gives customers peace of mind regarding unplanned costs because if an item breaks down it will be repaired or replaced for no extra cost. Tenants who transfer to another property with the same social housing provider can take their furniture with them, or it can be collected, safety-checked, recycled and refurbished. The service is focused on the needs of the customer and reducing risk to the landlord if a property becomes void.

We’ve seen the bleak effects of furniture poverty first hand. Taking people out of it can change their lives.

Helping tenants make a house a home

Magenta Living and Your Homes Newcastle have both used Newcastle Furniture Service to tackle furniture poverty among their tenants

Your Homes Newcastle

Sophie, tenant, Leazes Homes

Sophie (not her real name) had to leave her home quickly. As a victim of domestic violence, she had just enough time to pack a bag with clothes and a few personal belongings and get out. Life seemed to be unravelling at alarming speed. “I left a beautiful home and was put in hostel,” she says. “I lost everything.” That was in June 2020.

Sophie, 50, stayed in the hostel for nine months (“the first time I’d been in one, and it wasn’t a very nice experience”) before being invited to view a one-bed flat in Newcastle from affordable housing provider Leazes Homes, part of Your Homes Newcastle. Then the panic and worry set in, because she presumed it would be unfurnished. An empty box. Where would she get the money for a bed, a fridge, a cooker and a washing machine to make it a home?

“I was excited to see the flat but also very nervous because I had nothing to start a home with,” she says. “I really wanted out of the hostel but thought: ‘Where do I start?’ I’m on Employment Support Allowance because I have mental health issues. I’ve got nothing. Just my clothes. It was a scary situation.”

However, when Sophie saw the property she discovered that Leazes had furnished it with a full furniture pack from Newcastle Furniture Service. “I was really taken aback,” she admits. “The kitchen had a fridge freezer, cooker and washer, dinner service and cutlery. You name it. There was a two-seater sofa with a table, a brand new divan bed with bedding, quilt and pillows, and a new shower curtain and towels. It was ready to move into. Unbelievable, really. It basically allowed me to start again.”

She told the hostel she was leaving and stayed at the property that very night.

Sophie has now secured the tenancy on the flat and pays for the furniture and appliances with housing benefit. “It’s about £11.60 a week,” she says. “Because it comes straight off [my housing benefit] I don’t see any difference. I think it’s really reasonable. If I was on hire purchase it would end up being a lot more.”

Any items that break down are either fixed or replaced. And when Sophie saved up enough money for a new sofa, the one she had been using was taken away free of charge.

It’s a great feeling to be living safely and securely in a fully furnished place that she can call her own, she says. “I’m really happy here. I’m comfortable. I’ve got my life back.”

Magenta Living

Paul Anson, executive director of business growth and resilience, Magenta Living

Paul Anson has seen the effects of furniture poverty first hand. He recalls walking into a shiny new social housing property but then being shocked to discover that its tenant couldn’t even afford to have curtains at the windows. They had no furniture and were practically living in a cardboard box.

Their plight resonated with him. “On the one hand we’re producing the finest-quality homes we’ve ever produced as a sector,” he says. “On the other, there’s still an ongoing issue of access to basic furniture for some individuals and families.”

Magenta Living – the largest housing association in Wirral, which owns and manages 12,800 homes – is alive to this situation and tried to get to grips with it some years ago by buying recycled furniture for its social housing properties. Yet while this idea had merit, it was not entirely successful, Mr Anson says, because after purchasing the furniture, the Magenta team struggled to manage it.

“You need a lot of infrastructure to manage furniture,” he explains. “[Social housing residents] move on… so you need to bring the furniture back into your organisation, clean it and put it out into the community again. I think it was clear fairly quickly that we weren’t set up to do that.”

So, in 2017, Magenta approached Newcastle Furniture Service (NFS) to see if they could help. As a result, NFS began delivering items in packs to furniture-impoverished Magenta residents, and then removing it when their tenancies ended. Residents can choose the furniture they need, and pay for it via Universal Credit or housing benefit, so it’s a flexible and low-cost model for them, and a low-risk one for Magenta.

Even so, the service was slow to take off until Magenta employed a co-ordinator to oversee the scheme in 2020. “The appointment of the co-ordinator – who manages the relationship between housing management, the tenants and Newcastle Furniture Service – has led to a really significant take-up of that furniture vision,” Mr Anson says.

He admits that he was not initially sure what the demand for furniture would be, guessing that 50 packs might be requested on an annual basis. In actual fact, it has been a lot more: 110 packs of furniture were sent out to residents in the co-ordinator’s first year, and Magenta currently receives around 26 referrals a month.

Magenta staff have been supportive of the NFS model after seeing it in action. “They can see it’s an easy solution that aids tenancy sustainability,” says Mr Anson. “More importantly, it meets a really important need for those suffering with significant furniture poverty. It enables people [access to items such as] rugs, tables, beds, cookers, fridges and washing machines. And although what we’re offering is basic, it’s a quantum step versus nothing.”

Feedback from tenants has been hugely positive too, notes Leah Gibbins, growth projects manager at Magenta Living. “Some have even said it’s changed their lives, because they’ve either lived without these items or have invested in them using a high-interest loan,” she reveals. “Then the items break, which is an unexpected cost they can’t afford. Whereas, with this service, if something breaks, it’s replaced at no cost to the tenant. That means they’re not living with the stress and anxiety of wondering how they are going to afford to fix it, and also they’re able to create a home with the items, rather than just living in a house that we let to them.”

For Mr Anson, another advantage of the rental model is that it’s environmentally sound. “One of the best aspects is NFS’s customer service and their capacity and willingness to replace or repair any of the items that are on loan,” he says.