‘We would all starve to death’ if fire safety guidance gave absolute priority to life safety, says senior official

A government official who held responsibility for building safety guidance for more than 20 years told the Grenfell Tower Inquiry that the country would have “starved to death” if the rules were written by someone who gave “absolute priority to life safety”.

Brian Martin, former head of technical policy at the government department responsible for building regulations, explained his view that policy-makers needed to “balance the costs and benefits” of imposing new rules on industry.

The inquiry had been shown an email from October 2010 in which he commented that putting a prominent campaigner for residential sprinklers in charge of drafting Approved Document B (the government’s building guidance covering fire safety) would not “necessarily be in the best interests of UK Plc”.

“The nature of developing any policy, and safety policy is no different, is that you are balancing the costs and benefits of the two options,” said Mr Martin. “If you ignore one of those two balances, you don’t have a balanced policy. You have something which one might argue is too expensive.”

“Given that the provisions of [this guidance] are specifically directed to the protection of life safety, and not to the protection of industry or any other economic or commercial interest, what would be wrong with letting somebody… who had life safety as their absolute priority craft the approved document?” asked Richard Millett QC, lead counsel to the inquiry.

“The country would be bankrupt. We’d all starve to death, I suppose, if you took it to its extreme,” replied Mr Martin. “That’s the policy conundrum governments are faced with: you need to balance the cost of regulation with its benefits.”

“So death by fire or death by starvation and that’s for the government to choose between?” asked Mr Millett.

“I don’t think anybody talked about it in those terms, but that’s the principle.” said Mr Martin.

Mr Martin told the inquiry that at the time this email was sent, the coalition government had a “focus on trying to stimulate the economy by reducing the impact of regulation”.

The inquiry has heard from several of Mr Martin’s colleagues in the department that this focus on deregulation limited the focus on redrafting the fire safety guidance to ensure it was adequate.

Earlier, Mr Martin was questioned about the decision to add the words “filler material etc” to a passage of Approved Document B which required insulation to achieve the tough fire standard of ‘limited combustibility’ in 2006.

This passage is critically important to this phase of the inquiry, because the government has argued since the fire in 2017 that the words ‘filler material’ applied to the combustible plastic core of the cladding material used on Grenfell Tower, meaning it was banned by the guidance.

However, this interpretation has been widely disputed by industry figures and experts in the years since, who have argued that the standard which should have applied to cladding panels was the lower fire rating of ‘Class 0’. The panels used on Grenfell Tower were sold with a certificate saying they met this standard.

Mr Martin explained today that the introduction of the words to the guidance was made following a fire at The Edge building in Salford in 2005.

That blaze had ripped through metal sandwich panels on the exterior of the building which were held together with combustible polystyrene. Given that these panels appeared to comply with the Class 0 standard, it was felt that the guidance needed to be redrafted to rule out their use.

The inquiry has previously seen that Mr Martin proposed an initial wording which would have required all materials in an external wall to meet the ‘limited combustibility’ standard.

However, he said this was too broad and that the word ‘filler’ was elected to avoid impacting elements such as the structure of the building, which could be made of timber.

“Why not say that the core of an external wall panel should be a material of limited combustibility in the same way as insulation?” asked Mr Millett.

“Well that addresses that problem, but not all the other potential places that someone might use combustible materials in a modern wall,” replied Mr Martin.

Asked if he wanted people to “to take this broad portmanteau expression and work out for themselves what fell within it”, Mr Martin said: “Yes, I think to some extent, that’s what we were trying to do.”

He said he did not discuss the meaning of the word ‘filler’ with anyone outside the department, and the inquiry also saw that no reference was made to it in the consultation document about the changes.

Mr Martin said this was because the need to make the change had arisen “late in the process”.

“Did you intend to slip this under the radar at the last moment and hope people wouldn’t notice?” asked Mr Millett.

“I think there was a problem for the department in that the further we went, the more it risked disrupting the policy process,” replied Mr Martin.

Asked why he had placed the phrase under a heading which read “insulation materials/products” when he wanted it to apply to materials that were not used as insulation, Mr Martin said the ‘products’ in the heading was supposed to imply that the paragraph also applied to materials which were not insulation.

“How could you possibly have thought that?” asked Mr Millett.

“That’s what we thought at the time,” said Mr Martin. “It’s evident that it didn’t work, so I can see why anyone looking at me now thinks, ‘what were you doing?’ but at the time that’s what we were trying to do.”

He added: “I think there was a concern that by identifying a specific product, in a very prescriptive way, that might fall foul of not having consulted specifically on that and that there’s a risk of a manufacturer challenging the department and you find yourself dealing with a judicial review.”

Asked if this meant the choice of wording was “really more about keeping this sotto voce and under the radar”, Mr Martin replied: “I wouldn’t say it was more about that, but there was some of that in the thinking, yes.”

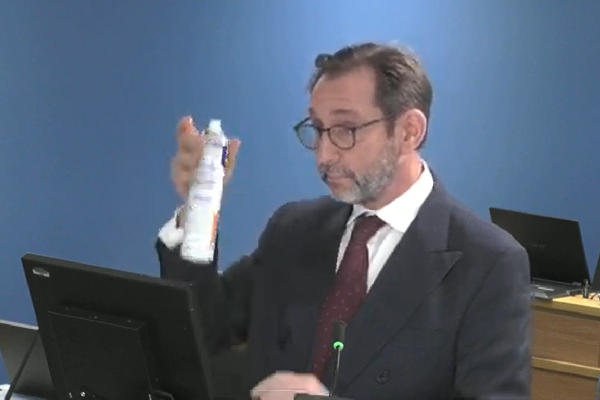

At one stage, Mr Millett produced a can of polyfilla to demonstrate that the word ‘filler’ could have an alternative meaning to construction professionals.

“Did you consider that the word filler might suggest some kind of product to 'fill' or block gaps or voids, such as expanding foam filler. We have some here. Polyfilla. Did anyone think well, filler could be thought of as that?” he asked.

“I don't think we thought that at the time, no,” Mr Martin replied.

“And... a filler is there to fill a void, as it does as we can see [sprays can]. Did anyone think at the time that in fact an external wall panel doesn't have a void. It's a composite panel made by bonding polystyrene or polyethylene to two sheets of metal?” asked Mr Millett.

“At the time we thought it was a good generic term to describe those things you inserted inside a construction,” replied Mr Martin.

Asked why he did not include a clear definition of the word within the document, he said: “If you’re trying to get people to think broadly then a definition can be counter productive.”

The inquiry then saw that the impact of the introduction of the word filler was not listed in a circular sent summarising the key changes when the document was published, a summary of the key changes contained in the new version of the approved document itself or the slides for a presentation given by Mr Martin and a colleague to explain the changes.

The inquiry also saw new emails showing Mr Martin discussing ACM fires overseas in the 2010s. In December 2012, referring to a fire in Dubai, he wrote: “Have you seen the video? It’s awesome.”

Asked if he was content that the term ‘filler’ was sufficiently well understood to prevent such a fire in this country, “notwithstanding the absence of a definition [and] the absence of a proper consultation”, he said: “The answer is the same. I thought it was OK.”

Later, the inquiry saw that in January 2013 he was contacted by a building control officer from Ipswich, who asked if insulated panels were permitted on a tall building.

Mr Martin forwarded the email to a junior colleague asking for his thoughts. When the colleague said he would look into it, Mr Martin replied: “Cool beans. The [approved document] needs to be read two or three times to work out what it means.”

Asked why he could not answer the question himself immediately, given his understanding of the 2006 changes, Mr Martin said he “would have been able to” but he “probably wanted Steve to do it so I could do something else”.

The inquiry then saw that in November 2013, Tony Baker, a senior figure at the Building Research Establishment (BRE), emailed Mr Martin to ask about the applicability of the word ‘filler’, citing “an increasing number of enquiries” from industry about its meaning.

Mr Martin responded saying he was “thinking out loud here”, and explaining that a “homogenous” board would be “fine” with a lower fire grade, but “a laminate of board with something else” should be ‘limited combustibility’.

He asked Mr Baker if this “makes sense” and asked him what he thought of the explanation.

“Your response tends to suggest that you had never really thought about this question before, is that right?” said Mr Millett.

“Perhaps not in the terms that are being talked about here,” said Mr Martin, adding that he did not have “God-like knowledge of every form of construction”.

“Yes, but you didn’t need to be The Almighty to know what was in your mind when you drafted [these passages] in 2006,” said Mr Millett.

“Yes and I have said, what was in my mind and I was testing with them here,” replied Mr Martin.

Asked if he viewed the approved document as “a sort of discussion document, something to provoke debates” rather than “a guide on how to comply with the functional requirements” of the building regulations, Mr Martin said: “I think it’s something twixt the two.”

The inquiry has previously heard that Mr Martin was asked to publish a 'frequently asked question' to clarify the meaning of filler material, given concerns about the use of ACM in July 2014. No such clarification was published before the Grenfell Tower fire.

The inquiry continues.

The filler debate explained

Much time at the Grenfell Tower Inquiry has been spent on the meaning of the words ‘filler material’ in Approved Document B, the official guidance on building regulations and fire safety.

This relates to a debate which has been raging since the days immediately after the blaze, about whether government guidance ever permitted the use of the aluminium composite material (ACM) panels used on Grenfell Tower.

Government witnesses have said the phrase was intended to require the core of composite cladding panels to meet the tough fire standard of ‘limited combustibility’, meaning combustible ACM would have been banned.

But another passage in the document said the “external surfaces of walls” were only required to be the lower standard of ‘Class 0’ or ‘Euroclass B’.

The panels used on Grenfell Tower were sold with a certificate that suggested they met these standards. Some have said this was all that the guidance required.

The meaning of the word ‘filler’ was not defined in Approved Document B and was never clarified by the government until after the Grenfell Tower fire, despite specific warnings that it was not widely understood.

The phrase was included in a passage headed ‘insulation materials/products’, despite cladding panels not being used as insulation. Some experts have said the phrase would have appeared to mean polyfilla-type products used to plug up gaps in an insulation system.

The question is not relevant to the compliance of the specific cladding system used on Grenfell, which utilised combustible insulation and therefore required a large-scale test or desktop study to comply. It did not have one.

However, it is deeply relevant to the government's broader responsibility for the use of dangerous materials on high-rise buildings.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters