Recommendation to review guidance following ‘catastrophic’ test on Grenfell-style cladding ‘just got missed’, says official

A recommendation to review fire standards following a “catastrophic” 2001 test on the cladding material later used on Grenfell Tower “just got missed”, the official formerly responsible for the guidance said today.

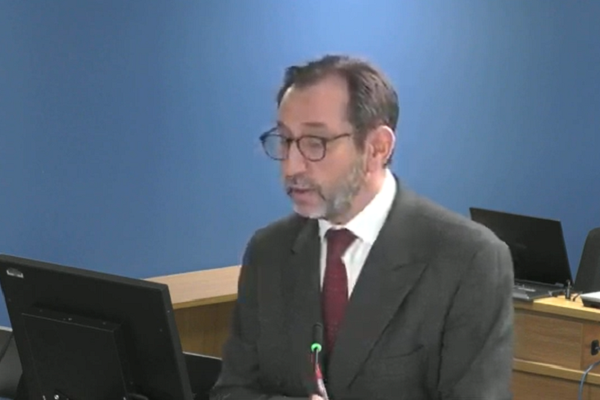

Giving a second day of evidence to the inquiry into the Grenfell fire, Brian Martin accepted that this explanation “sounds awful”.

However, he denied keeping quiet about the weaknesses in the guidance to “keep the market sweet” and insisted he had not been covering up the testing and “praying fervently” that it would not be discovered.

As the inquiry has previously heard, the UK government commissioned a series of cladding tests in 2001 to help establish the pass/fail criteria for a new large-scale test.

One of these tests, carried out on 18 July 2001, used an aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding panel with a polyethylene core – the same material which would later be installed on Grenfell Tower.

This test showed the system performed “catastrophically”, with flames reaching 20 metres high and the test stopped less than six minutes into its 30-minute duration out of concern for the safety of those present.

This should have been a major concern, because the ACM panel possessed a ‘Class 0’ fire rating, meaning it complied with guidance in force at the time for use on tall buildings.

When the results of the tests, carried out by the Building Research Establishment (BRE), were summarised for the government in September 2002, its report advised that the panel had “satisfied Class 0 requirements”, but had still “proved to be one of the worst performing products” in the larger-scale test.

It said “these issues may require further consideration”.

At the time, Mr Martin was employed by the BRE and had worked on the testing programme, but was also seconded to government offices two to three days a week to advise on a review of building regulations guidance on fire safety contained in Approved Document B.

He was asked why the recommendation to the government to review the Class 0 standard was not made more clearly, given the devastating scale of the test failure.

“Given that the test resulted in catastrophic, full scale failure… Why was this recommendation expressed in such feeble terms?” asked Richard Millett QC, lead counsel to the inquiry.

“I don’t know,” replied Mr Martin.

“It [the recommendation] doesn’t spell out… in clear terms to government that if they don’t review Class 0 people might die,” said Mr Millett. “And what we all want to know is why.”

“I wish I had a better answer. I don’t know,” replied Mr Martin.

The government ultimately did not do anything to respond to the recommendation and left the Class 0 standard in the guidance until December 2018 – 18 months after the Grenfell Tower fire.

This was despite earlier warnings from a select committee investigating cladding fires that the standard be replaced with a requirement that cladding panels be entirely “non-combustible”.

“The deregulatory environment [implemented following the election of the coalition government in 2010] was a decade off into the future,” said Mr Millett. “What possible reason was there for the government, in whose offices you sat half the week, not acting on the advice there, oblique though it may have been?”

“I don’t think there would have been any reason not to act on it,” replied Mr Martin. “And again this sounds awful, but I think it just got missed.”

This testing was never mentioned by the government, even after the Grenfell Tower fire, until it was disclosed to the inquiry and partial data was leaked to the BBC in September 2021.

“Are you able to give us an assurance that you and Anthony Burd [a civil servant in the department at the time] did not sit on this data… for the full nine years that you were a full time civil servant, hoping and praying fervently that it would never see the light of day?” asked Mr Millett.

“I can assure you that neither of us would have done that,” replied Mr Martin.

Asked if there was any innocent explanation for the details not being released, he said: “Tragically, I think it just got forgotten and fell between the gaps.”

“One gets the slight sense, Mr Martin, that there’s some sort of problem about coming clean with government and telling them Class 0 was a problem” said Mr Millett. “Is there anything in that?”

“No, I don’t believe anyone at the department or anyone at BRE would have deliberately concealed this,” replied Mr Martin.

Approved Document B is intended to guide builders in how to meet their legal responsibility to ensure the external walls of a building “adequately resist the spread of flame”.

Mr Martin accepted that ACM would have complied with the Approved Document at this time, “but wouldn’t have met the functional requirement”.

“What on earth is the point of permitting this through [Approved Document B] in circumstances where it would not meet the functional requirement?” asked Mr Millett.

“I don’t think that’s a thing that you’d want to do,” Mr Martin replied.

He claimed not to have been present at the test, but said the result was raised with him by his BRE colleague Dr Sarah Colwell. Mr Martin said she showed him a piece of the cladding panel in the office and described how “the aluminium melted away, exposed the polyethylene, and then the polyethylene began to burn”.

“Did you have any thoughts at the time along the lines of ‘well, we can’t be having any of that above 18 metres in this country’?” asked Mr Millett.

“I honestly don’t remember thinking much more about it,” replied Mr Martin. “I think I assumed… that Sarah was dealing with it.”

Despite this testing being used as the basis for the pass/fail criteria for the large-scale test, Mr Martin said the results “didn’t come up for discussion” when he worked on creating this criteria with Dr Colwell only a year later.

“It sounds hard to believe, but that’s right,” said Mr Martin.

“It does sound hard to believe,” replied Mr Millett.

The ACM product was one of 14 different cladding systems subjected to the fire test, which the BRE had selected after what was supposed to have been a “comprehensive survey” of the UK’s built environment.

However, as the inquiry has seen previously, the BRE only sent the survey to 45 local authorities and only obtained 13 full responses.

Mr Martin accepted that this work was “very far from a comprehensive survey of the UK building stock”.

“Why was it so woefully incomprehensive?” asked Mr Millett.

“I think from experience these sorts of surveys are often very unsuccessful. There’s nothing to compel the building owners and local authorities to respond to them,” replied Mr Martin.

The inquiry also saw that when Mr Martin came to draft the pass/fail criteria along with his colleague, Dr Colwell, a first draft contained a passage which referred to the weaknesses in the test for Class 0.

But when a second draft was published in 2004, this reference had been removed.

Asked why this passage “disappeared and did not reappear”, Mr Martin said he did not remember “a conscious decision to remove it”.

“Was one of the reasons why these words disappeared from here the need to preserve Class 0 to keep the UK market sweet?” asked Mr Millett.

“Absolutely not,” replied Mr Martin.

The inquiry has seen previously that lobbyists for various industries, including the manufacturers of foil-faced plastic insulation, had pushed for the retention of Class 0 when it was suggested that it might be replaced with tougher European tests, which their products might not achieve.

Earlier, the inquiry saw a report Mr Martin wrote in 2001 which claimed the passage containing the Class 0 standard in Approved Document B “restricts the combustibility of external walls of high buildings”.

However, he accepted Class 0 was not a test of combustibility and the standard did not apply to the entire external wall.

“Why was there any room for this slackness, this imprecision?” asked Mr Millett.

“I don’t think it was deliberate,” replied Mr Martin. He said that as he got “older and wiser”, he would have become “more pedantic with the use of that word” (combustibility).

Towards the end of the day’s evidence, Mr Martin was asked about a decision in 2006 to add the words “filler material” to a passage requiring insulation used on high rises to be of limited combustibility – a tougher standard than Class 0.

This was done following a serious fire at The Edge in Salford in 2005, which had spread via Class 0-rated sandwich panels used to construct the external wall.

The inquiry saw that a consultation document did not contain the word “filler material”, which Mr Martin said he intended to cover the core of a composite cladding panel.

Instead, it was added after the consultation had concluded, which meant its general meaning was never checked with the industry.

Mr Martin told the inquiry this happened due to time constraints, which meant he had not formulated the wording he wanted to use by the time the consultation went out. However, this was six months after The Edge fire.

“What's the rationale for just letting it drift off rather than actually sitting down at a desk, thinking through what wording will work and putting it out there [for consultation]?” asked Mr Millett.

“I think… this was the quickest way to get the consultation draft moving,” said Mr Martin.

Since the Grenfell Tower fire, the government has insisted that the word “filler” meant the type of cladding used on the tower did not comply with the guidance, because of its combustible core.

However, industry figures have fiercely disputed this, noting that the Class 0 standard remained in the guidance until around 18 months after the Grenfell Tower fire with no clarification ever issued to explain that ‘filler’ referred to the core of a composite panel.

At the start of the day’s evidence, Sir Martin Moore-Bick, the 75-year-old retired judge who chairs the inquiry, revealed that he has tested positive for coronavirus and has been suffering mild symptoms.

He is observing the hearing remotely over Zoom until it is safe for him to re-attend in person.

The inquiry continues, with further evidence from Mr Martin tomorrow.

Who is Brian Martin?

Brian Martin had been responsible for official building regulations guidance on fire safety, contained in Approved Document B, for almost 18 years by the time of the Grenfell Tower fire.

He was the person within the department “to whom others would turn” to answer questions on this topic.

When she gave evidence, Melanie Dawes, the former permanent secretary at the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), was asked if it was “pretty dangerous” to have the responsibility for all this “falling on one man’s shoulders”.

“Yes, I do. I think it ’s a single point of failure that had been allowed to be created,” she said. Asked to explain how this happened, she said it reflected budget cuts, the localism agenda and the fact that “regulation was not seen as something valuable, it was seen as something that created costs and burdens”.

Mr Martin has no formal fire safety or engineering qualifications. His qualifications amounted to a diploma in building control surveying obtained around 25 years ago.

He had trained as a joiner and carpenter after leaving school, before rising to site manager. Asked if this gave him any fire safety experience, he said: “I would have installed some fire doors.”

Aged 22, he became a building control surveyor, working first for Westminster, Tower Hamlets and Dartford councils, and did review fire strategies for some complex projects, including the Bluewater shopping centre in Kent.

In 1999, he applied for a job at the Building Research Establishment (BRE), the former national testing centre which had recently been privatised. The BRE had a contract to support the government with a review of Approved Document B and within weeks of starting, Mr Martin was seconded to the department’s offices for two to three days a week to support this work.

Mr Martin would go on to take a permanent role at the department in 2008 as ‘principal construction professional’. This saw him take on primary responsibility for Approved Document B. The inquiry has already heard about many critical warnings regarding the looming danger of a cladding fire which were issued to him in this role.

In November 2017, five months after the Grenfell fire, he was promoted to head of technical policy, leading the team of specialists who oversaw changes to building regulations and guidance.

However, in September last year he moved to the planning directorate. He said he had been “encouraged” to find a new role given “the challenges associated with my attendance at the inquiry and the attention I was getting in the press”.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters