Official accepts government made ‘false representation’ about cladding guidance after Grenfell fire

A civil servant has accepted that the government made a “false representation” about its official guidance after the Grenfell Tower fire, but denied that doing so was a “planned, deliberate and underhanded” attempt to protect its position in the aftermath of the deadly blaze.

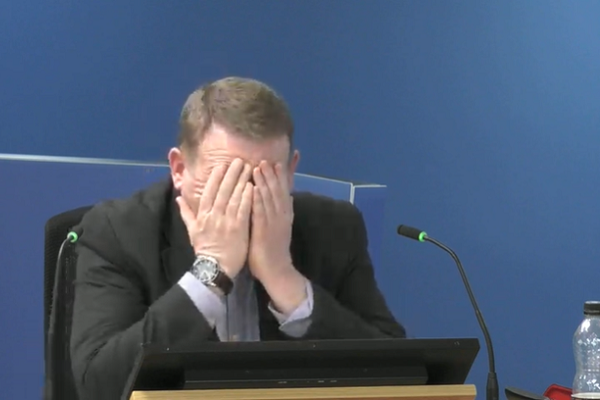

At the end of more than seven days of cross-examination before the Grenfell Tower Inquiry today, Brian Martin also accepted “to some extent” his personal responsibility for “a catalogue of failures, errors and omissions” in the years before the blaze.

In a tearful closing statement, he told the inquiry “there were a number of occasions where I could have potentially prevented” the fire from happening.

The final sections of his mammoth examination, the longest of more than 100 witnesses who have appeared before the inquiry, focused on his actions in the days after the fire which killed 72 people in June 2017.

He was asked about a controversial letter sent eight days after the blaze, in which the government claimed official guidance in Approved Document B, for which he had been responsible for almost 18 years, banned the use of the combustible aluminium composite material (ACM) panels which had been installed on the tower.

The letter said this was due to a paragraph which required “filler material” to meet the tough fire standard of ‘limited combustibility’ – and this applied to the combustible plastic in the core of the composite panel.

Mr Martin had been warned on multiple occasions that this was not clear – and that dangerous ACM was being used due to a belief that a less restrictive standard applied to cladding. He had been asked to clarify this point, but has told the inquiry he “forgot” to do so.

The letter, sent by senior civil servant Melanie Dawes, claimed this phrase meant the requirement of ‘limited combustibility’ materials applied to “any element of the cladding system”. Mr Martin has already accepted in his evidence that this was not the case.

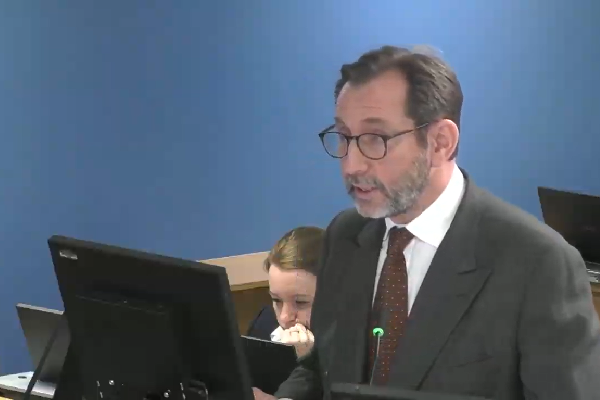

“Do you know how this false representation of the government’s position… came to be included in this footnote?” asked Richard Millett QC, counsel to the inquiry.

“It’s a mistake on my part, I must have missed it,” said Mr Martin, adding that he was “probably really tired at that point”.

“Are you sure this wasn’t a planned, deliberate and underhanded attempt by you and those around you to rewrite history in the light of the 71 deaths at Grenfell [on the night] in order to protect the government’s position after the event?” asked Mr Millett.

“No,” said Mr Martin.

The inquiry saw an email chain which showed the letter was drafted by figures including Sir Ken Knight, a former government advisor and current chair of its expert panel, Martin Shipp, a former technical development director at the Building Research Establishment (BRE) and consultant Colin Todd.

Mr Shipp appeared to draft the footnote, with Mr Todd amending it to “hammer it home” that combustible cladding was banned.

Mr Todd, now an expert witness to the inquiry, has previously supported the government’s interpretation of this critical phrase in a report to the inquiry, saying that it would be “illogical” for the words to exclude the core of an ACM panel.

He did not mention in his report that he had helped draft the footnote setting out this interpretation for the government in the immediate aftermath of the fire.

Mr Millett then asked if Mr Martin had informed Ms Dawes of a series of events previously covered in his evidence when he briefed her about the guidance in Approved Document B two days before the letter was sent.

These included:

- That he had introduced the phrase ‘filler material’ to the guidance in 2006 “without any external scrutiny, without consultation, without a definition, at the last minute and under the radar”

- That the change had “not been publicised in the normal way” to avoid the department being “subjected to judicial review” by industry

- That he had not clarified the meaning as requested following an industry summit in June 2014 and he had subsequently been warned the guidance was “not clear, open to interpretation and misleading” with regard to ACM cladding

- That he’d assured others in the department that a huge cladding fire like those experienced in the Middle East “should not happen here” due to the provisions in the guidance, without noting that they were unclear

- That he had been warned by a “reputable” cladding consultant in January 2016 that ACM was in wide use in the UK and that the situation was of “grave concern”.

Asked if these issues were “highly pertinent and of fundamental and obvious importance” for Ms Dawes to know, he said: “I’m not sure they were at the time. Other people will think differently, but at that time, I was asked to brief her on what the building regulations said and how they intended to work. And I did that to the best of my ability.”

“When you put them all together, do you accept that they reveal a catalogue of failures, errors and omissions on your part, Mr Martin?” asked Mr Millett.

“I think to some extent, yes,” he replied.

The inquiry has previously seen that in the days immediately after the fire, Mr Martin contacted various industry experts with a “pre-prepared script” which claimed the cladding was banned by the guidance.

He had asked them to repeat the claim publicly in order to “rebut” a news report that the cladding material was not banned.

Asked today why he took this step, he said he was instructed to do so by “somebody senior in the press office”.

“Did you consider it appropriate to approach these organisations with a pre-prepared script to be presented as if it were the independent view of an independent expert in support of the government’s interpretation of the guidance after the fire?” asked Mr Millett.

“It’s not something I’d ever been asked to do before. I understand it’s not unusual,” said Mr Martin, adding that as a “junior official” if “you get told to do something like that, you get on and do it”.

He was also asked about a meeting on the Saturday after the fire, with a list of experts he helped assemble to brief the minister on the government’s next steps.

Part of the meeting was to establish the cause of the rapid fire spread and whether or not the blaze was “an isolated incident”.

But Mr Martin, who “led the discussion” did not reveal that he had been warned the cladding was being widely used in the UK, or discuss the confusion over the guidance, or reveal that an ACM cladding system had drastically failed a government-commissioned test in 2001.

“Was one of the reasons, or the reason, why you mentioned none of the matters that I’ve just put to you that you realised, in the starkest possible terms, that the catastrophic series of errors [were] certainly yours and you didn’t want to own up to?” asked Mr Millett.

“No,” replied Mr Martin.

“Is there any other explanation?” asked Mr Millett.

“Because we were focused on the immediate response,” said Mr Martin.

Asked at the end of his evidence if he would have done anything differently, Mr Martin struggled to restrain sobs as he said: “I find it difficult to express how sorry I am for what’s happened to the people of Grenfell Tower.

“Over the last few months, I’ve been looking through the evidence and the documents and when you line them up in the way that we’ve done over the last seven days, it became clear to me that there were a number of occasions where where I could have, potentially, prevented this happening.

“I think over time I’d become entrenched in a position where I was focused on what I could do to improve the Approved Documents and didn’t realise just how big the problem was.

“What I will say is that the approach that successive governments had to regulation had an impact on the way we worked, the resources that we had available and perhaps the mindset that we’d adopted as a team, and myself in particular.

“I think as a result of that, I ended up being the single point of failure in the department.”

The inquiry continues tomorrow with evidence from James Wharton, a former government minister with responsibility for building regulations.

Brandon Lewis, the former fire minister and now Northern Ireland secretary, gave evidence earlier today.

Who is Brian Martin?

Brian Martin had been responsible for official building regulations guidance on fire safety, contained in Approved Document B, for almost 18 years by the time of the Grenfell Tower fire.

He was the person within the department “to whom others would turn” to answer questions on this topic.

When she gave evidence, Melanie Dawes, the former permanent secretary at the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), was asked if it was “pretty dangerous” to have the responsibility for all this “falling on one man’s shoulders”.

“Yes, I do. I think it ’s a single point of failure that had been allowed to be created,” she said. Asked to explain how this happened, she said it reflected budget cuts, the localism agenda and the fact that “regulation was not seen as something valuable, it was seen as something that created costs and burdens”.

Mr Martin has no formal fire safety or engineering qualifications. His qualifications amounted to a diploma in building control surveying obtained around 25 years ago.

He had trained as a joiner and carpenter after leaving school, before rising to site manager. Asked if this gave him any fire safety experience, he said: “I would have installed some fire doors.”

Aged 22, he became a building control surveyor, working first for Westminster, Tower Hamlets and Dartford councils, and did review fire strategies for some complex projects, including the Bluewater shopping centre in Kent.

In 1999, he applied for a job at the Building Research Establishment (BRE), the former national testing centre which had recently been privatised. The BRE had a contract to support the government with a review of Approved Document B and within weeks of starting, Mr Martin was seconded to the department’s offices for two to three days a week to support this work.

Mr Martin would go on to take a permanent role at the department in 2008 as ‘principal construction professional’. This saw him take on primary responsibility for Approved Document B. The inquiry has already heard about many critical warnings regarding the looming danger of a cladding fire which were issued to him in this role.

In November 2017, five months after the Grenfell fire, he was promoted to head of technical policy, leading the team of specialists who oversaw changes to building regulations and guidance.

However, in September last year he moved to the planning directorate. He said he had been “encouraged” to find a new role given “the challenges associated with my attendance at the inquiry and the attention I was getting in the press”.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters