‘Life-safety risk’ in social housing from crumbling aerated concrete

A lightweight concrete that decays over time and has been linked to collapses in schools poses a potential “life-safety risk” in social housing, experts have warned.

Reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) was widely used in UK construction from the mid-1950s to the 1980s.

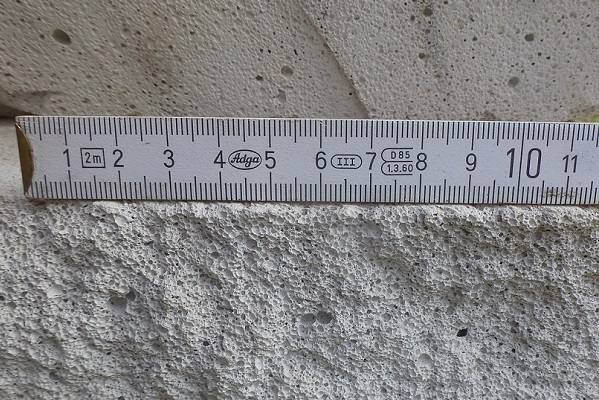

Filled with air bubbles and containing no coarse aggregate, the material was cheap and lightweight, and was particularly popular for flat roofs and external cladding.

It has long been known to decay over time and recent instances of sudden roof failures in schools has led to concerns about its use in public buildings such as schools and hospitals.

However, experts told Inside Housing that RAAC was also used in public housing projects – many of which are likely to still be in use with housing providers unaware of the risks.

Philip Morris, a chartered architect and managing director of Philip Morris Consulting, said: “It was good for the roofs of buildings, cladding panels and floors, but not necessarily shear walls. It was widely used by municipal architects in council housing projects.”

He said he has seen particular issues on roofs where water ingress had impacted the junction between the RAAC plank in the roof and the wall.

“RAAC concrete absorbs water. It’s like a sponge. You increase the load because you’ve got all these holes filling with water and, all of a sudden, you’re increasing the loading on the end of that plank and that’s when we end up with collapse,” he said.

Mr Morris said the impacts could range from chunks falling away to a full building collapse “like a pack of cards”.

“It is undoubtedly a life-safety risk,” he added. “Not just to residents but to passers-by, if we are talking about external cladding panels coming loose and falling to the ground.”

Professor Chris Goodier, an expert in construction engineering and materials at Loughborough University and an expert on the use of RAAC who has advised government departments, said he had “heard nothing RAAC-related” with regard to social housing, “but that doesn’t mean it’s not there”.

“If it’s built in the 60s and 70s and has a flat roof, then it’s very possible if not likely [to contain RAAC]. If it’s a tiled roof, then no. Tower blocks are less likely [to contain it], though possible. [A building] two to four storeys high with a flat roof is most likely,” he added.

Mr Morris added: “You could end up with cladding panels detaching. You’ll see more roofs failing. And also because of climate change, we’re getting more one in 100-year storms. That means you have got more water on the roof, so therefore there’s more chance of collapse.”

He said he would recommend visual surveys of flat roof blocks built in the period where the material was in wide use.

“Look at the underside and see if there’s any cracks in the plaster board, because the plaster board will be fixed directly to the timbers brackets in the RAAC concrete so if the concrete has moved, the chances are it will show cracks in the plaster board,” Mr Morris explained.

He also advised housing providers should check operations and maintenance manuals as well as building drawings, but conceded that these may have been lost over time – particularly where ownership of a building had changed.

Greg Carter, legal director at law firm Winckworth Sherwood, added: “Housing providers might have a claim under the defective premises act if the building is still within the 30-year timescale. Insurance policies may cover the work, but it will depend on the individual policies. I would advise any housing provider who discovers it to seek legal advice.”

The Institution of Structural Engineers currently has a RAAC study group, which includes a list of members with experience of working with RAAC panels, and published guidance in February 2022.

The Department for Education has published guidance for schools here. Almost 600 schools are undergoing urgent structural checks.

Sign up for our development and finance newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters